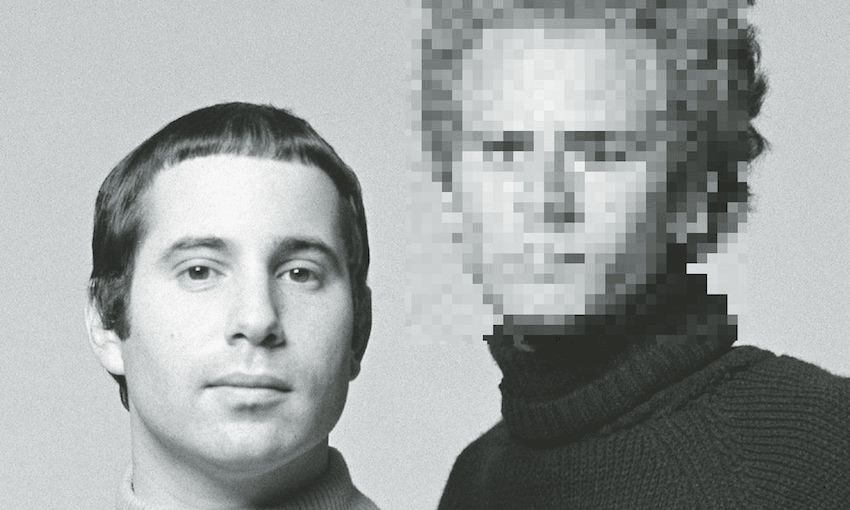

A new biography is being lauded as an “intimate and inspiring narrative that helps us at last understand Paul Simon”. But is that possible when there’s no sign of Art Garfunkel?

Before starting Robert Hilburn’s Paul Simon: The Life, I was reading Fa Fa Fa Fa Fa Fa: The Adventures of Talking Heads in the 20th Century by David Bowman. My God, there was a dysfunctional group. Was there ever a musical relationship as damaged as that between David Byrne and Tina Weymouth? Bowman’s interviews with Weymouth are the making of the book. He just had to point his microphone and wait for the vitriol to flow. Fa Fa Fa Fa Fa Fa positively seethes with toxic tension and passive aggression.

If only the Paul Simon story had such enmity to animate it; such drama to draw on. If only it had its own Tina Weymouth. But hold on a minute. It does have its own Tina Weymouth; there was a musical relationship as damaged as that between Weymouth and Byrne.

Simon and Garfunkel.

Theirs was a friendship and partnership (make that ‘friendship’ and ‘partnership’) that spanned half a century, from meeting at the end of sixth grade and their 1957 hit as Tom & Jerry, “Hey, Schoolgirl”, through their 1963–1970 years as Simon and Garfunkel, and on to the last of their many reunions in 2010. With Simon’s lyrical and musical craftsmanship and Garfunkel’s exquisite voice, they enjoyed a formidable run of records: “The Sound of Silence”, “I Am a Rock”, ‘”Homeward Bound”, “America”, “Mrs Robinson”, ‘“The Boxer”, “Cecilia”, ‘“Bridge Over Troubled Water”‘…

The demand for all those reunions is testimony to the records’ indelibility, as is Simon and Garfunkel’s continuing cultural reach: from Kruder & Dormeister’s droll pastiche of their Bookends album cover, to Camera Obscura’s fancy-dress nod to the back cover of the Bridge Over Troubled Water album for their “Sweetest Thing” video, to a three-hour Latvian play where the only thing to break the silence is the duo’s music, to Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver movie named for one of their songs. That’s not even touching on the cover versions. (A favourite.)

But so often Simon and Garfunkel could barely be in a room together before they were at each other’s throats. “I never forget, and I never forgive,” Garfunkel once said, the memory of Jerry abandoning Tom for a run at solo success festering a long time. They “wouldn’t have a meaningful conversation for five years”, setting the pattern for many other years.

For Simon, it rankled that, after he remained in the wings while Garfunkel gave early performances of “Bridge Over Troubled Water” at New York’s Carnegie Hall and London’s Royal Albert Hall, Garfunkel took bow after bow, introduced the pianist, but didn’t even mention Simon. It also rankled for Simon when people assumed Garfunkel wrote the songs and was the frontman, since he was so tall and handsome (the looks and the locks), while Simon was so short and balding.

When Simon decided to quit the duo in 1970, he didn’t even bother to tell Garfunkel. Pettiness – or perhaps we should just call it intransigence – abound. In 1974, Simon’s about-to-be-ex-wife Peggy fell in love with an apartment in New York’s Dakota building, so he set about buying it for her and their son, Harper. Only a rival emerged. By a quirk of fate that confirms God as a Catskills comedian, it was Garfunkel. Simon and Peggy met Garfunkel and his then wife to talk them into backing out. Did they? Did they hell. So the two couples ended up bidding against each other, pushing up the price of the apartment. Simon and Peggy won. (More fate: Simon went on to date Carrie Fisher, whose best friend was Garfunkel’s girlfriend Penny Marshall. Boom tish.)

And so on, and so on.

All of which would have been fine if they had chosen to stay well away from each other. To have drawn a line under everything in 1970. But they kept returning to the well, forgetting how poisoned it was: a Saturday Night Live guest appearance here, a world reunion tour there.

A lifetime of getting the pip and inflicting hurt on each other. A lifetime, perhaps, simply out of sync with each other. Maybe we can take those questioning quote marks away from ‘friendship’ and ‘partnership’. Relationships can be … complicated. But they don’t stop being relationships.

The bones of all this are in Hilburn’s biography. But there’s no flesh on the bones. Because although Hilburn can boast more than 100 hours of interviews with Simon, the first time Simon has talked to one of his many biographers, he hasn’t managed even an hour’s interview with Garfunkel, instead having to rely on previously published comments for the few Garfunkel quotes he includes. It’s a glaring omission, not even alluded to in the acknowledgements or elsewhere in the book.

Oh brother, Art, where thou?

*

Hilburn loads the dice very much in Simon’s favour. In the acknowledgements, he writes of “difficult moments” in their interviews; “he wasn’t as eager early on to talk about his private life and sometimes bristled when a touchy subject came up, leading occasionally to heated discussions”; “There were even times when I feared the project was close to breaking down.”

We could’ve done with some of that heat in the main body of the book, because you get no sense Hilburn pressed very hard on anything; what is left on the page is a proficient but pedestrian plod that reads more like an extended newspaper profile than a proper biography. (Hilburn was chief pop music critic of the Los Angeles Times for more than three decades.)

It’s not a very challenging newspaper profile either, simply scraping the surface. Hilburn does allow for some criticism of Simon, but it’s from third parties rather than delivered himself, and he always comes back to privileging Simon’s position.

It’s not an authorised biography; after all those interviews, Simon left Hilburn to it, because he wanted “a complete and objective account”. But it might as well be authorised, with its cosiness exemplified by all the family snaps. Snaps you might find on Simon’s mantelpiece – eg twin photographs of Simon and son Adrian when both were around 18 months old and looked astonishingly similar (how cute!) – but don’t expect in a serious study.

The back-page blurb calls it “a landmark book that will take its place as the defining biography of one of America’s greatest artists”; “an intimate and inspiring narrative that helps us at last understand Paul Simon, the person and the artist”.

Well, Simon is certainly one of America’s greatest artists. That at least is true. Hilburn is happier deciphering the music. And on the tour dates, chart positions and Grammy statistics. If tour dates, chart positions and Grammy statistics were the key to a man’s soul, Hilburn would have Simon nailed.

Simon was, of course, quite right to ditch Garfunkel in 1970. He had clearly outgrown the folk pop limitations of their partnership, as was immediately apparent from the expanded musical palette of his self-titled debut solo album, with its reggae-infused lead single “Mother and Child Reunion”. A song so good that even learning its title was inspired by a chicken-and-egg dish on a Chinese restaurant menu can’t diminish it.

Where Simon was wrong, and Garfunkel too, was in not keeping his distance thereafter. Garfunkel could have gone back to architecture (for which he studied at Columbia University); could have continued to dabble in acting (his performance in director Nicolas Roeg’s dark, dark, dark/mad, mad, mad 1980 movie Bad Timing being a career highlight, and not only because of the dapper threads he wears in it); could even have continued to sing such nonsense as “Bright Eyes“, if he so wished. Could have avoided being dicked around by Simon. Or dicking him around in return.

Simon, meanwhile … what did Simon need those reunions for? Nostalgia? The money? To be kind in his own way to Garfunkel? To lord it over Garfunkel? These are not questions Hilburn goes near, being more comfortable recounting facts than digging psychologically.

Ultimately, relationships aren’t about rights and wrongs. They are what they are; they go where they go. They are as mysterious as some of Simon’s songs (and even rhyme like one). But they are still open to illumination. A teeny-weeny bit of illumination. (A hundred hours of interviews!)

Still, at least there’s the music. Paul Simon, There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, Still Crazy After All These Years, One-Trick Pony, Hearts and Bones, Graceland, The Rhythm of the Saints – that’s nearly 20 years with hardly a foot wrong. (And what was mostly wrong with One-Trick Pony was the folly of the movie it was attached to.)

If the albums that followed – Songs from the Capeman, You’re the One, Surprise, So Beautiful or So What, Stranger to Stranger – didn’t make the same impact, they were better and more adventurous than most other artists at the same stage in their careers. Surprise’s collaboration with Brian Eno being the biggest, well, surprise. Maybe Simon has become a bit of a noodler on recent albums, but noodling isn’t holding back the likes of Thundercat.

The long musical apprenticeship Hilburn records at the beginning of the book (in and out of the fabled Brill Building, on the British folk circuit) supports the wisdom of Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule for refining talent. By the 1970s, combined with his magpie tendencies and impeccable taste in collaborators, it ensured albums that were easily a musical match for a decade highpoint such as Joni Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns. And a lyrical match too. Simon can tell a simple affecting narrative – “The Late Great Johnny Ace”, for instance. He can send language leaping over itself in a breathless display – think “The Boy in the Bubble”‘. And he can occupy all the stations in between.

He’s not afraid of dense thickets of phrasing. So much so that, when Hilburn cites a quote by early 19th-century politician Daniel Webster that Simon encountered at school, it could be taken for a Simon lyric: “on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent … on a land rent with civil feuds.” Deft, diffident, the songs are expressed in a voice of unsurpassable wistfulness. It’s always 4pm on a winter’s Sunday afternoon in Paul Simonland.

“The Boy in the Bubble” is the opening song of Simon’s most lyrically accomplished album. And his most controversial. Graceland saw Simon’s magpie tendencies truly get the better of him, leading him to record in South Africa with local musicians, ignoring the United Nations anti-apartheid cultural boycott in place at the time.

The resulting music was indeed tremendous. And the album contained arguably his greatest song, the title track. Which in turn contained arguably his greatest lines: “She comes back to tell me she’s gone/As if I didn’t know that/As if I didn’t know my own bed/As if I’d never notice/The way she brushed her hair from her forehead.”

But if ploughing ahead with the album against all criticism is typical of Simon’s self-determination, it is also typical of an arrogance and single-mindedness that are part gift, part curse. (Witness his One-Trick Pony movie fiasco and The Capeman Broadway musical disaster from which Songs from the Capeman was the salvaged album.) It’s so frequently his way or the highway.

History may or may not have proved Simon right for persisting with Graceland – I for one have never been decided – but Hilburn does the political arguments against the album a disservice by not giving them more credence and as ever giving Simon the upper hand.

Sometimes you wonder if Hilburn appreciates the full significance of what he’s writing, with the meaning submerged between the lines: there is a whiff of solipsism about Simon transporting South African singers Ladysmith Black Mambazo to London for further Graceland recordings because he didn’t want to return to Johannesburg since “he couldn’t tolerate any more of the harsh apartheid regime”. Poor him.

The same solipsism emerges again on Simon’s most recent album, when in a song called “Wristband” he frames the plight of “the homeless and the lowly” through a comparison with a rock star not being allowed in the backstage door of one of his concerts because he doesn’t have his wristband on to show the guard.

Still, the man who gave us such songs as “American Tune“, “Kodachrome” and “René and George Magritte with Their Dog After the War” can be forgiven the occasional misstep. And if his conduct hasn’t always been exemplary in service to his songwriting and to his career, maybe he can be forgiven that too.

One of Simon’s friends is composer Philip Glass. (Others include as varied a bunch as political columnist Thomas Friedman, artist Chuck Close and, er, The Dream Academy’s Nick Laird-Clowes, he of “Life in a Northern Town”.) Writing “The Boy in the Bubble”, Simon realised he had passed on some of his best lyrics to Glass for a collaboration they were considering. “Was it fair to ask Glass, who had already built music around the lyrics, to give them back? Probably not, but Simon’s need ruled the day. He called Glass, promising to give him new lyrics in return. Glass wasn’t thrilled, but he understood, and he graciously returned them, which included one of the song’s most memorable phrases: the ‘days of miracle and wonder.’”

Simon’s need ruled the day. Songs – careers – of miracle and wonder perhaps require a streak of ruthlessness. A similar theme runs through the Talking Heads story. They have friends and collaborators in common (Brian Eno, Philip Glass) – perhaps Paul Simon and David Byrne should get together. Maybe Art Garfunkel and Tina Weymouth too.

Paul Simon: The Life by Robert Hilburn (Simon & Schuster, $37.99) is available at Unity Books.