Scottish historian Hamish Dingwall is working on a book about New Zealand suffragist Mary Ann Müller and wrote this essay as bait, basically. If you have any sort of archive (letters, photographs, a diary) regarding Mary or her life, no matter how small the snippet, Dingwall would love to hear from you. Email books editor catherinewoulfe@thespinoff.co.nz and we’ll forward it on.

In the icy early days of February 1814, the River Thames froze solid along the short span from London Bridge to Blackfriars. Since Christmas, temperatures had fallen below zero across England. Monoliths of ice drifted downstream and were trapped at the low stone arches of London Bridge. A cold platform gradually formed on the mighty river. The path was unstable in places where the black waters licked its jagged edges. One young man, a plumber, named Davis, attempted to carry lead across the unsteady route by Blackfriars but sank between two masses of ice, to rise no more. By tradition, when the Thames froze, the watermen, deprived of their usual income ferrying passengers, put on a Frost Fair. The scene was merry and magical in spite of the danger. Thousands of revellers ventured out to sample three favoured luxuries – gin, beer and gingerbread – served from many booths on the ice.

A man named James Norris and his new bride were in the crowd then. They had married in secret in a city church that morning then walked the mile south to Three Cranes Stairs where they stepped onto the ice and joined the celebrations. He had her name printed at one of the presses that had popped up amongst the taverns, selling poetic pieces that marked the great frost.

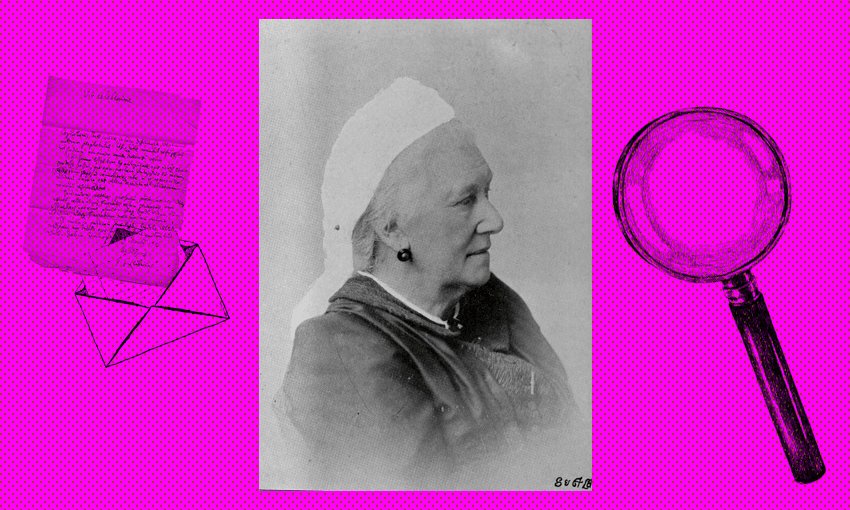

Mary Ann Müller has been called the pioneer worker for the enfranchisement of women in New Zealand – the first modern nation to let women vote in Parliamentary elections – and it is 200 years since her birth. The progressive aspects of New Zealand’s politics are known worldwide, and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s compassionate leadership approach has recently attracted attention across the globe. Yet Mary Ann Müller’s own contribution to New Zealand’s political heritage is virtually unknown in London, her birthplace.

Müller wrote pamphlets and articles under the pen name Femmina, arguing for equality in the law. She was forced to work in secret as her husband was bitterly opposed to any reform. She lived in Nelson where she knew many of the men who were playing their part in building the colony, including several future prime ministers. She planted the seeds of equal property rights and the franchise in conversation with them but rarely met with encouragement. In 1869 she wrote “An Appeal to the Men of New Zealand” which proposed the vote for women. To modern wisdom it is astonishing that her opinions were so controversial – at that time the duty of a woman to subject herself to her husband was widely accepted. The mystery is why she set out to change the fabric of society as early as she did. Her personal story, before she made the long journey by ship to New Zealand with two young children, provides some clues.

Mary Ann Müller was the daughter of the newlyweds that day at the Frost Fair, James Norris and his bride, also named Mary. Norris had every advantage in his early life. His father was a doctor who rose to be Master of the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1816. James and his three brothers were educated at the venerable public school Charterhouse. One of the brothers was later knighted for his services to the government. By comparison, James’s own activities are at least obscure if not nefarious. Within a decade of his marriage, he had left Mary with his two daughters, sworn her to secrecy about that first marriage – bigamy was a crime – and remarried the daughter of an Alderman of London. Perhaps he left Mary for money or for status, or both. Whatever the reason, his desertion presumably created hardships for his first family. Mary Ann Müller knew him only as godfather until his death when she was 18. That’s when her mother told her the story of the marriage and the Frost Fair, recalling the memento that was printed to mark the occasion. Later in life, James Norris enjoyed financial success and lived with his second family in a mansion in a newly fashionable part of London. After his death, his family moved to the Isle of Wight. At the time when Mary Ann published her “Appeal” in New Zealand, her step-siblings were living on their inheritance in one of the finest villas in Ventnor, known as “Mayfair by the Sea” and about the most prestigious resort that Victorian society knew.

Mary Ann was surely not the only person then or since to have a complicated relationship with her father. The “Appeal” is written in stridently insistent and logical prose, corralling the best arguments in favour of women securing the vote. It was sufficiently impressive to earn a letter of congratulations and encouragement in her quest from the liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill. There is no hint at personal circumstances. The question arises: was it her father’s treatment of his wife that first drew her attention to the injustice of the laws towards women?

The Frost Fair of 1814 lasted for little more than a week. Warmer climates and a new London Bridge, built in 1831 with five wide stone arches, meant that Old Father Thames’ waterway never iced over again. In contrast, the frozen society in which her mother’s options were severely constrained, whilst her father could recreate a new and prosperous family life, only began to thaw in the next century. The vote for women in New Zealand came in 1893. It was another quarter-century before some, not all, women were enfranchised in the United Kingdom.

Mary herself faced a lonely struggle for equality before any of that came to pass. She died in 1901, and letters she wrote to her fellow suffragist Kate Sheppard in the final years of her life are filled with gratitude and delight that the female franchise had finally been won. They are tinged with sadness at her own failure to do more, and frustration at the rheumatism in her fingers that prevent a good writer from communicating as she would wish. Nonetheless, she looked forward to a time when women might even make laws in the parliament for which they could now vote.