In which Dan Kelly – our man in New York – heads into Soho to see the world’s greatest writer speak at a bar.

Meeting your heroes can be risky: expectation loves disappointment. But like everyone before me, I didn’t care. This was Karl Ove Knausgaard, Norwegian literary sensation and author of the critically acclaimed My Struggle series, a six-volume autobiography that blurred the line between reality and fiction, the man people compared to Proust – of course I wanted to meet him. He would be speaking at a bar in Soho on Saturday and I was going, a distinct sense of unreality present as my train headed into the city. Could it really be?

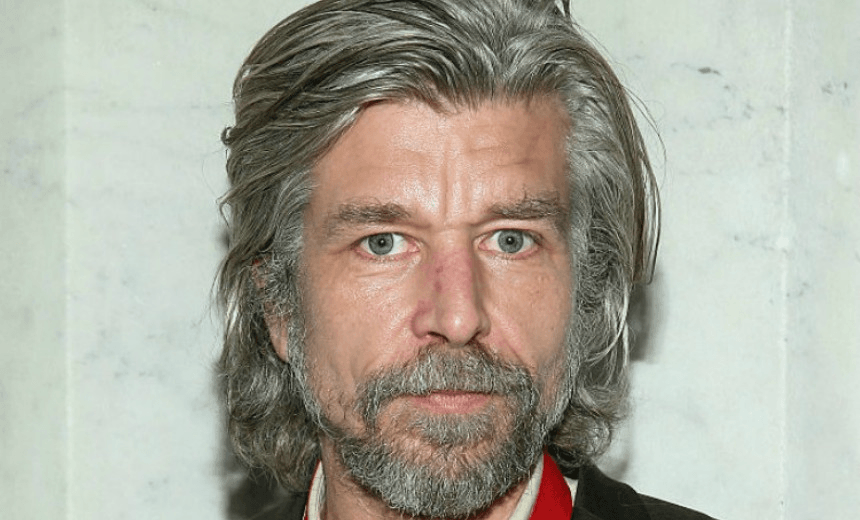

The evening was part of the Norwegian-American Literary Festival, a series of public events organised by The Paris Review, now in its fifth year. There was a small queue, a bag check (yes fastidious American bouncer, you can have my water), and then there he was, on stage in a sharp brown suit, a tall man adjusting the mic stand. The rock star aspect was hard to ignore. Here he was, the boy who had dreamt of fame, felt possessed by his call to greatness, consumed by the need to prove the doubters wrong, now in New York, on stage, running his hand through his white hair, all his dreams come true.

People stood around waiting, drawn by his presence. The room was dark, a club of sorts, with dimly lit bars down both sides. I studied the crowd, slightly in awe of who might be there – but there was little to gleam in the gloom: people in brogues, an old woman in a suit, a man in a polo shirt talking on his phone – just more New York faces, all equally unknown.

The event wasn’t solely about Knausgaard, but the photos told another story. He disappeared briefly then returned, and with no introduction launched into his opinion on why the opening reading, The Birds by Tarjei Vesass, is a classic on par with say Ulysses, or Madame Bovary. He spoke calmly and clearly, his English accented but excellent – this was a book we needed to read. He finished and was promptly sent back, a sheepish grin on his face. He was meant to say, if we would like a copy, the book is for sale.

In the following four-person panel on “The Literature of the Real”, Karl Ove sat quietly as the topic – clearly a nod to his own personally based realism – was hijacked into a broader discussion of what literary truth might entail. When finally addressed, he was ready. He cited a number of Scandinavian writers and suggested that yes he was part of a trend towards increased honesty, the demand for which was growing – no surprise given the artifice in which we, subjects of late-stage capitalism, swim.

There was a break and I sat on the steps outside, watching the street. Karl Ove come outside for a cigarette, and I watched as he was accosted by a short woman, her book signed, the selfie taken, his eyes dark and tired but still smiling, so tall and distant, his greatness lived as fame now. I wondered, what did he make of all this, he who had written so strongly about his distaste for pretence, his burning desire for authenticity? It wasn’t like I knew him, but when you’ve read five books detailing the minutiae of a life it’s hard not to feel some sense of affinity. He had seemed so confident on stage, so practised. Maybe he’d changed; I guess we all did.

In the final panel, a discussion between Knausgaard and Norwegian director Joachim Trier on “Memory in Film”, it seemed like there was more of the Knausgaard I knew. Trier was confident and entertaining, feeling out ideas as he went and in comparison Karl Ove seemed reserved, tentative. At one point he was asked to give a defence of literature – he’d previously said it was the only way to represent what happens internally – and he looked visibly defeated, smiling still but speechless, at first, as if to say, surely you don’t expect me to answer that? But such is the burden of fame, here, the expectation that you, one fallible human, are to have answers, definitive canonical answers, for any and everything that might come up. I wouldn’t say I pitied him, but it was hard not to feel some empathy.

Later, Trier raised the issue of trauma and the difficulty we have in defining it despite all it does to move us, arguing that it, like the sublime, has value precisely because of its ineffability. Even if we can’t see it, it can show through in a work, often accidentally; indeed, art is perhaps one way to parse trauma. And yet, for all Knausgaard’s work speaks to this – one of the central preoccupations of My Struggle is the impact of his father, a cold, abusive man – he explicitly denied that trauma was a concern, said that he didn’t feel traumatised.

I wonder, and this is where I am perhaps on, as they say, thin ice, whether that trauma, the absence of a positive model of intimacy, isn’t behind his stated need for validation, the conflicted outcome of which brings him, a self-described nervous, emotional man, to a position of public notoriety – here represented by myself um’ing and ah’ing afterwards over whether I should thank him or is that just too American and what am I after, anyway? I thought about the conflict, my own desire to respect his space, privacy and the shallowness that is the celebrity selfie – as if to say: look, me too! In ego does fandom lie…

But still, there is something else. Art not only as a way to parse trauma, but perhaps heal it too, an invitation for that most reassuring of lines: you are not alone. So I turn, think fuck it, tell him you fool – and there he is, this giant complex man, walking towards me and I shake his hand, thank him, admit my fandom and he smiles, looks nervous, mumbles through small grey teeth and I am gone, him to his life and me to mine, off but not alone.