For all its faults, writes Danyl Mclauchlan, the Labour-turned-Act politician’s 1996 book speaks for something that now seems almost old-fashioned: a group of true believers who had a vision of how the world works.

This story was published in February 2021. Read Richard Prebble’s reflections on I’ve Been Thinking, 25 years on, here

They were called “Choose Your Own Adventures”, and they were a publishing craze back in the 1980s. They were novels – mostly for kids and teens – broken up into sections. The reader got to choose what actions the second-person protagonist took, then flipped forwards or backwards to the appropriate section to learn the consequences of their decision. “Turn to page 15 to fight the monster, or page 100 to run away.” A lot of these books were fantasy or sci-fi stories and they functioned as a gateway drug channeling a generation of young nerds into computer games and roleplaying.

So perhaps I shouldn’t have been so surprised to pick up Richard Prebble’s I’ve Been Thinking – published 25 years ago to promote the newly formed Act party that Prebble led into the 1996 election – to find that about a quarter of it consisted of a choose-your-own-adventure novel. In I’ve Been Thinking, YOU are the associate minister of finance and minister for state owned enterprises in the 1980s, just as Prebble was, and YOU have to choose the best course of action to save the nation from revolution or bankruptcy.

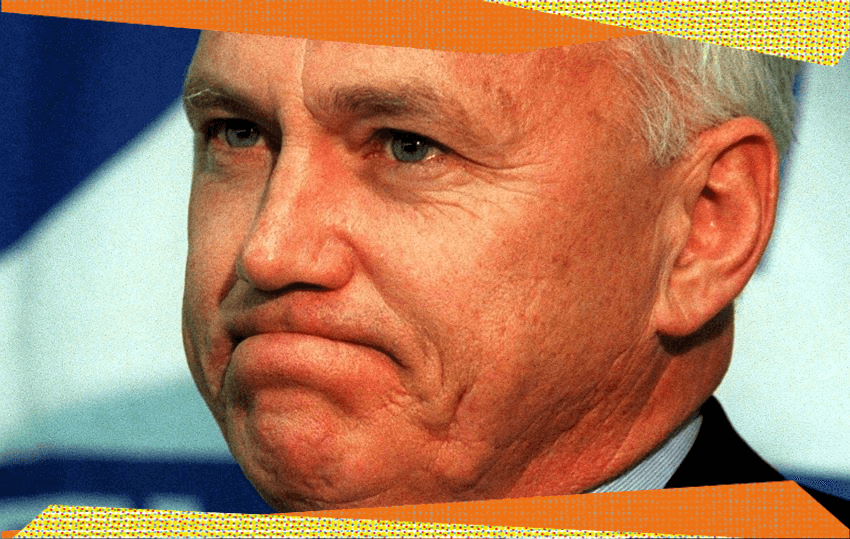

The term “neoliberal” has come to mean “anything intellectuals don’t like”, but as much as the term ever meant anything it described Prebble, the former Labour MP who commercialised and privatised a gigantic proportion of New Zealand’s public sector as a senior minister in the historic Lange-Douglas government, then went on to found the Act party and lead it into parliament, where he advocated for lower taxes, less state spending, less government, more law and order.

I’ve Been Thinking was, according to Prebble, a declaration he made as minister and which struck terror into the hearts of his officials. The title was widely mocked. One of the cover blurbs for my copy of the book is from Pam Corkery: “We must stop Richard before he thinks again.” But it was a very widely read book, back in the day. Act reckoned they either sold or gave away 300,000 copies of this and its sequel I’ve Been Writing. Even if a lot of these 300,000 were never read, that’s still orders of magnitude more than the couple of hundred retail sales most New Zealand political books attract. And it’s an explicitly ideological book: a book of ideas, which is also unusual for New Zealand politicians who mostly want to sell themselves rather than their belief system.

Choose Your Own Adventure books always had a very strident morality built into them. They sometimes gave you the option to lie or cheat or steal, but they always punished you for it. Prebble’s Choose Your Own Adventure functions the same way, only instead of saving a stranger from drowning or giving the blind beggar a gold coin the correct course of action is always to cut state spending, sack huge numbers of public servants and privatise their departments.

To be fair, Prebble makes a strong case for the shittiness of the challenges the fourth government faced. Consider a couple of his scenarios: In the early 1980s farmers received guaranteed prices for meat from the state, which incentivised them to breed and slaughter vastly more lambs than the export market could support, and which then sold on international markets for about a tenth of the cost of production. As associate finance minister do you abolish guaranteed prices? As minister for state owned enterprises do you continue to borrow huge sums of money to pay for forestry and railways jobs that appear to create no economic value? Do you open the telecommunications and air travel markets up to competition?

If you do choose to deregulate, commercialise and privatise everything then “Coungratulations! You are a Rogernomics supporter!” and the book rewards you with economic and political triumph, while failure to follow this path leads to various disasters: general strikes, election losses, national bankruptcy, losing your electorate seat.

Prebble was a lawyer who went into politics in the mid 1970s (he won Auckland Central!) Like a lot of young Labour and National MPs of that era he was “radicalised” as he put it, by the dysfunctionality of the vast, ineffectual, eye-wateringly expensive and rapidly deteriorating public service of the Muldoon government. The parts of I’ve Been Thinking that aren’t a choose your own adventure are mostly anecdotes about how terrible the public service was before Prebble annihilated it, how much better the commercial companies that replaced it were, and how amazing it will be if the rest of the bureaucracy is supplanted by the private sector.

I don’t believe all of Prebble’s stories. I do not believe, for example, that by the mid-90s the ACC system had incentivised large numbers of young men to pretend to be injured so they could spend all day “pumping iron”, and that there were large gyms in our inner cities catering to this clientele. But most of Prebble’s yarns are about the Post Office, which also ran the phone network which later became Telecom and then Spark and Chorus, and which was the largest single employer in the country, or the Railways, which had a monopoly on the nation’s shipping and passenger transport but operated at a loss of a million dollars a week.

I worked in the New Zealand tech sector in the mid 90s: most of the older engineers had worked at the post office, and they spoke about their experiences there like grizzled war veterans describing a world we just couldn’t comprehend. Yes, there were warehouses filled with unsent mail that periodically got buried, or burned. Yes, companies sometimes went bankrupt because the post office disconnected their phones and couldn’t or just wouldn’t activate them again. Yes, there were expensive mail sorting machines that sat in their boxes because the Public Service Association wouldn’t let the department use them.

The intellectual architect of neoliberalism was an Austrian economist called Fredrich Hayek. Prior to Hayek the central metaphor in economics was that an economy was like a machine, and economists were experts who could fix and calibrate those machines. It was a metaphor that strongly leaned towards centrally planned economies. The more of the economy that the state owned and controlled, the more of the machine its economists could calibrate and optimise and fix, and the better off everyone would be. And this was a metaphor that even right-wing or conservative politicians accepted, or at least failed to refute until Hayek came along and burned it to the ground.

“The economy”, Hayek pointed out, is an abstract term describing all the people working, creating, renting, building, consuming; living their lives. It’s the accumulation of all the decisions and choices that vast numbers of people make all day, every day. You can draw a massively simplified diagram of “the economy” that looks like an engine or some other machine, and you can generate statistics that summarise parts of that information. And these models and statistics can often be useful, but you can’t use them to predict and plan with any accuracy.

But Hayek argued, all these forecasts and models allowed social scientists – especially economists and the politicians they advise – to pretend they were real scientists or real engineers, when they weren’t. Because humans aren’t like water molecules, or any other simple physical system. They’re intelligent individual agents making choices based on complex information that’s local to them, and which can’t be aggregated in a statistic or forecast by any expert. So any centrally planned economic system – like the New Zealand Treasury predicting what the value of New Zealand lamb should be on the economic market – was innately doomed. Only a free market, which allowed many individual agents to freely exchange information on value, could solve what Hayek called ‘the local knowledge problem.’

Prior to Hayek, conversations about free markets versus central planning were mostly moral debates, which advocates of central planning tended to win because the amoral outcomes of capitalist systems were very apparent. Hayek changed that: it didn’t matter how moral you claimed your centrally planned utopia was going to be, it just wasn’t going to work. And the more complex your economy, and the larger the scale and more interlinked with the rest of the world, and the more your so-called experts interfered, the more catastrophically it would fail. It was Hayek’s Constitution of Liberty that Thatcher famously banged on the table at a Conservative Party conference announcing “this is what we believe,” and their confidence in the inevitable failure of planned systems that lead them to confidently announce “there is no alternative.”

The ideology – still a fringe idea in most political and economic circles – picked up credibility in the 1970s when it adopted a key idea from political science that complemented Hayek’s knowledge problem. “The principal-agent problem”. How do you empower or employ someone to act in your interest, and then ensure that they do so instead of acting in their own self interest? How do you make sure a politician serves the public? (You hold them to scrutiny via the media and hold regular elections.) If you run a company how do you make sure your employees are working hard in the company’s interest, rather than just stealing all your stationery?

The neoliberals realised that state monopolies and government bureaucracies could be defined as acute principal agent problems. I’ve Been Thinking begins with a story from Prebble’s time as minister of railways. A farmer came to him to complain that the railways had lost his tractor. He’d complained to its officials, but they’d failed to find it. Prebble asked them to look again, and they explained that it was somewhere between Hamilton and Taumarunui, but they had no idea where. So the farmer got in his car and drove the line between Hamilton and Taumarunui and eventually found his tractor in a siding, along with six other wagons the department had lost. The centralised department had no information about its cargo and no incentive to serve its customers, because they were a monopoly in which no one ever got fired.

All of the many stories about government ineptitude in Prebble’s book fall into either or both of these famous categories: local knowledge problems and principal-agent problems. Neoliberalism was a global phenomenon but it really captured the hearts and minds of New Zealand politicians and economists because thinkers like Hayek, or Ludwig von Mises or Milton Friedman seemed to be talking about New Zealand. All their hypothetical problems with states and planning and the ineptitude of experts described Robert Muldoon and the New Zealand government. Hayek saw it all coming!

The great promise of neoliberalism was that you could use free markets to solve the problems that centrally planned governments could not, and this would deliver better economic results. The great failure of neoliberalism is that this didn’t work. Prebble admits that he destroyed a lot of jobs during his time in government. David Lange apologised to all the people whose lives his government ruined. They knew they were causing phenomenal pain. But There Was No Alternative, and the gains from that pain, once the market would be unleashed, would be spectacular.

Philosophers have this phrase: beware of the person who has only read one book. The neoliberals knew there were two big problems in political economy, and they were caused by governments and solved by markets. But it turns out there are lots of problems in large scale, technological economies, some of which can only be solved by the bureaucracies that the neoliberals dismantled.

Prebble’s book doesn’t mention that there was a global share market crash in 1987, and in New Zealand this triggered a deep and prolonged economic recession, because our share market had been deregulated (by Roger Douglas and Richard Prebble). Tens of thousands of New Zealanders had invested heavily in a share market that was dominated by companies that turned out to be worthless.

Then, in the 1990s, the neoliberals in the National government deregulated the building industry, which then went on to build tens of thousands of schools, homes and apartment buildings using substandard materials that meant all the buildings leaked, and filled with toxic moulds, and needed to be torn down and rebuilt. Experts argue about the cost of all this but it’s probably over twenty billion dollars.

These were asymmetric information problems that were very hard for individual consumers to solve, because of the complexity of the share market or construction industry, but are very easy for the state to solve. It just appoints a couple of experts to set regulations preventing fraudulent companies from publicly trading, or substandard building materials being used in thousands of homes.

Then there are coordination problems. If there’s a pandemic outbreak how does the free market close the borders, and put people in quarantine, and operate track and trace systems? Obviously it doesn’t: you need state capacity, and nations that have eroded that capacity because of the conviction that “the state can’t create value” have done very poorly in the face of the pandemic.

Also: public servants aren’t the only instance of the principal-agent problem. The idea was originally used to discuss political leaders. And if politicians or parties are accepting donations from individuals or companies or lobbyists, and passing laws that favour them that’s a very acute principal-agent problem. And the neoliberals were, and remain, very close to business and lavishly funded by high net worth donors. Most of the commercialisations and privatisations Prebble presided over turned out to be disasters, with Air New Zealand and BNZ and the Railways all needing massive taxpayer bailouts, or wound up being repurchased by the government. But the wealthy advisors on the sales, who also purchased the assets, and were often generous donors to the political parties, made staggering sums of money, and no one could ever really explain how or why.

But the deepest intellectual failure of the doctrine was the conceit that you can remove the state from the market, which is a self-organising system that will naturally emerge when left alone. States create markets. But if politicians pretend that they don’t, they can accept money from the rich to optimise the political and economic system for their benefit, and then pretend this outcome is neutral and market driven. It’s just what works. There is no alternative. None of the economic gains the neoliberals promised ever came. Instead the benefits from the anemic economic growth of the next 30 years went to a much smaller number of already wealthy households and individuals, and quality of life indicators for the poorest people in the country deteriorated. In the final analysis the neoliberals themselves suffered from the local knowledge problem, in that the governments they deregulated were more complex than they could comprehend, and from the principal-agent problem: they were working for the companies that funded their political parties, rather than the citizens who elected them.

The neoliberals weren’t the first ideology to start out with a plan to make the world a better place and quickly find themselves somewhere shockingly amoral and corrupt. And they won’t be the last. But I do wonder if they’ll be the last intellectually coherent political movement; the last group of true believers that had a vision of how the world works (“This is what we believe”) and how to fix it, and actually carried it out. Now we have Trump flailing at the White House. Justin Trudeau marching against his own government’s climate policies. Jacinda Ardern criticising capitalism in opposition, then locking all our economic settings in place once in government. There are plenty of critics of the world the neoliberals built, but very few ideas on how to replace it. All the options in the choose your own adventure of modern politics seem to lead back to where we already are, a place that nobody likes, but can’t seem to escape from. A world with no alternatives.