In literature, disability is everywhere. But more than a century after Dickens gave us Tiny Tim, writers often fail to make disability anything other than a narrative crutch. Robyn Hunt, writer, disability consultant and co-founder of the Crip the Lit project, explains.

The use of disability as metaphor and plot device has been described as “narrative prosthesis”. An academic take on the topic, released in 2000, makes the point that: “while other marginalized identities have suffered cultural exclusion due to a dearth of images reflecting their experience, the marginality of disabled people has occurred in the midst of the perpetual circulation of images of disability in print and visual media”.

We’ve had unreal stereotypes like Forrest Gump, inspirational and cured – he throws off his leg brace. In Peter Pan, Captain Hook is a villain and is eaten by a crocodile. In One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest the victim of horrendous “treatment” is killed. The Hunchback of Notre Dame is both victim and monster and dies. Evil witches by the Grimm brothers and Frank L. Baum are fair game with short sight and facial differences. Clara, Heidi’s best friend is an unspecified invalid who is miraculously cured by country kindness and goodness.

In other words: in fiction, disability is everywhere. But rarely – too rarely – is it handled well.

Fiction’s fixation on disability spans all periods and genres, from saints’ narratives through 19th century novels and the modernist obsession with eugenics, to the contemporary concern with mental distress.

It was the Bible, fundamental in western culture, that began negative views of disability, and the New Testament began miracle cures. But for the modern reader, popular literature of the 19th century has been most influential.

There’s the object of charity, the pitiable Tiny Tim in A Christmas Carol, the best-known of several disabled characters Charles Dickens used to either wrench the hearts of, or provide amusement for, his readers. Tiny Tim also began the ‘cure or die’ trope that persists today.

But Dickens’ more sympathetic approach, so cloying today, was then a departure. At that time disabled people were still commonly feared and seen as monstrous. Physical differences were often interpreted as outward manifestations of inner depravity or punishment for moral failings.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island takes up that theme with a vengeance, with Blind Pew and Long John Silver as the disabled villains of the piece. The author makes use of disability as a symbolic device, rather than creating a realistic disabled character.

The themes exemplified in Dickens’ and Stevenson’s writing persist.

There have also been plenty of what I call ‘improving’ books written for children featuring disability – books that use it to make a moral point. What Katy Did, by Sarah Chauncey Woolsey writing under her pen name Susan Coolidge, was published in America in 1872. Twelve-year-old Katy is always getting into trouble but really wants to be beautiful and beloved. An accident leaves her an “invalid” but she learns to be good and kind and so recovers with the help of the teeth-grindingly saintly Helen.

A 2016 re-telling of the story in a British context by children’s writer Jacqueline Wilson follows the original plot and characters without the moralist overtones. Also called What Katy Did, it’s simply a good story, well told, with believable characters and a more realistic ending – without a cure.

Charity case, cure-or-die, disability as punishment, the saintly recovery – these tropes have continued in various forms, and with new developments in popular literature. D H Lawrence does a hatchet job on Sir Clifford in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, depriving him of masculinity, potency and agency so there’s cause for the scandalous affair of his wife and the gamekeeper. Sir Clifford is created to make a point. I read this book when it was still considered reprehensible for the sexual content, but it was Lawrence’s disability take-down that I found more offensive. It put me off him for life.

Earlier writing hasn’t been totally without authenticity; the recognition by a disabled reader of character, plot and action that’s accurate, realistic, insightful and relatable – the hallmark of the best writing about disability. The short story The Yellow Wallpaper, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, directly confronts the fearful stereotype of the Madwoman in the Attic in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. The Yellow Wallpaper is a feminist text on the treatment of women, and of depression. Many more modern authors – Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath and others – have written authentically about madness. Women have often written more thoughtfully about madness than men.

Of Mice and Men, released in 1937 by John Steinbeck, has another stereotype at its heart, and eugenicist overtones. Lennie, the simple “child” giant who doesn’t know his own strength symbolises the loss of innocence of the USA. He must die.

Some modern popular writers like Jodi Picoult and Jojo Moyes have used disability shamelessly to exploit in sensational and commercial terms the question of who gets to live a valuable life, and related ethical dilemmas to prop up their plots. In My Sister’s Keeper, Picoult creates a story of a “sibling saviour” who decides to say no, with all kinds of predictable consequences. And of course one of the girls has to die. These writers deliberately court controversy to sell books, with seemingly little inside knowledge, although they claim to do their research.

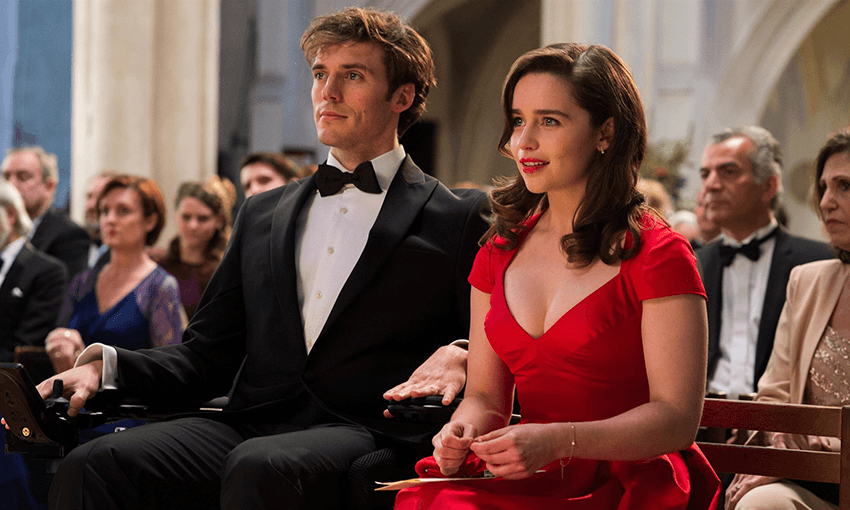

In Moyes’ Me Before You the improbable plot and characters are led to the well-worn stereotype that death is preferable to disability. Here, because of disability, love doesn’t conquer all. The book, and in particular the film sparked protest by disabled people around the world, including in New Zealand, who’ve had enough of the perception of disability as a fate worse than death.

Even literary prizewinning books are problematic. Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See is one. Although it has an element of fable, it annoys some blind readers, probably because they so seldom see themselves realistically reflected. A friend had misgivings about the way the blind heroine’s father teaches her to orient herself and navigate the city. A blind writer whose work I like and respect says this character, Marie-Laure, “is unlike any blind person you’ll ever meet. She’s a genius on the inside but fully helpless so that her aged father has to bathe her. Yuck.” Marie-Laure is not killed or cured.

The flip side of the fate worse than death is what the late Stella Young called “inspiration porn”: the portrayal of disabled people as inspirational solely or in part on the basis of their disability, one-dimensional saints who exist simply to warm the heart of the non-disabled reader. An evolution of my “improving” books.

In these stories, a brave, gritty, or determined disabled person overcomes obstacles, not letting disability get in the way of their dreams. There are plenty of examples. Wonder by R J Palacio published in 2012 tells the “inspiring and heartwarming” story of a 10-year-old boy with a facial difference who finally gets to go to a mainstream school, overcome bullying and find acceptance. Mostly it isn’t too bad. But the end is cringeworthy.

In the 1980s there were several anthologies by disabled women writers, exploring the disability experience, reflecting the rise of the disability rights movement.

Two novels stood out in the late 80s and early 90s. They were, unlike many books featuring disability, readily available in New Zealand. Skallagrigg, 1987, by Michael Horwood, centred on disabled people. All the central characters are disabled. The book reflects the changes from outdated institutions to community living and services in the UK, as here at that time. Significantly disabled characters, some who are unable to speak, have humanity, character, personality and increasing agency. Most have cerebral palsy. Skallagrigg also includes the beginning of electronic communication technology and its revolutionary impact. Disabled readers related to its verisimilitude. Shame the central character had to die.

Ben Elton’s satirical Gridlock, published in 1992, is hilarious, with a cast of strong off-beat but believable disabled characters who take no prisoners. It’s risky as Elton, like Horwood, isn’t disabled. But like Skallagrigg, the book works. Disabled readers “get it”, and the “crip” humour. The hero, for example, “had had the words ‘Geoffrey spasmo: Satan’s Dog’ written in studs on his first leather jacket and worn it to school” – that’s Elton reclaiming the language of insult with great panache. I laughed out loud on re-reading it. I used to use one section, “The Chair Gets Interviewed”, as a training tool. In it, the job applicant’s wheelchair grows to assume complete dominance over all the characters and the process. A clever take on a real experience. Several people die, messily.

J.K. Rowling’s amputee Afghanistan veteran with PTSD, Cormoran Strike, is well-researched and believable in the tradition of the flawed detective. He’s stayed alive so far.

Autobiography of a Face, 1994 by Lucy Grealy is a memoir, a popular genre for disabled writers. She explores the effects of appearance discrimination from the inside. Sadly she died in 2002 from an accidental drug overdose.

Memoirs are often particularly meaningful for disabled people. Too Late to Die Young by Harriet Mcbryde Johnson is another readable memoir. She also wrote a Young Adult novel, Accidents of Nature, which was well received by disabled readers. Sadly, she too died relatively young.

There is a thread of disability authenticity running through New Zealand writing. It begins with Katherine Mansfield, through Robin Hyde, June Opie, Janet Frame, Karen Butterworth, Mary O’Hagan, Te Awhina Arahanga, Trish Harris, all writing from the inside, several on the theme of mental distress.

They have published diaries, letters and journals, novels, memoirs (including commentary on disability identity and the mental health system) poetry, non-fiction and YA fiction. There’s room for more thoughtful and well-written disability memoirs like those of Mary O’Hagan’s Madness Made Me and Trish Harris’ The Walking Stick Tree. Becoming a Person is worth noting because, although it’s by a non-disabled author, John McRae, the voice of the extraordinary Robert Martin is loud and clear.

YA and children’s writing is fertile ground for writing about disability. David Hill’s See Ya, Simon, 1992 is thoughtful, but the central character has to die. Other writers, such as Mandy Hager and Erin Donohue, have written YA books with good disability stories and real disabled characters.

Disability is wonderfully diverse. There is no one right way to represent us, just as there are many ways to misrepresent us and our stories. Whoever is writing, authenticity is critical. Disabled children and adults are hungry to see ourselves, our stories reflected in what we read.

Most books written with disabled characters are by non-disabled authors, often for non-disabled audiences. Disabled and non-disabled readers bring different world views and frames of reference.

Non-disabled people can write authentically about disability but not by exploitation. A disabled writer won’t automatically understand everyone else’s impairment, but there’s inside knowledge and a head start if you care to take it.

A small country with a small market and publishing community means achieving diversity in literature isn’t easy. Most publishers and editors are non-disabled, though I know several excellent disabled editors. The internet brings international availability and multi-formats, but more quality local writing is needed.

We need more of everything: more variety in disability, genres, and narratives, more disabled main characters, and more characters with multiple impairments because that’s the way we are and our world is. We need more happy endings, humour, romance and adventure. More subversion of tropes and more complexity, nuance, depth, breadth, and intersectionality.

The emerging international ‘criplit’ movement encourages disabled people to write about ourselves and our community, with the mantra of ‘nothing about us, without us’. In New Zealand, Crip the Lit is part of that movement.