Guy Somerset compares the new novel by Jennifer Egan to Winona Ryder’s performance in Stranger Things. It’s not a compliment.

Historical fiction is a friend to no novelist.

As if the challenges and perils of writing a novel weren’t mountainous enough already: character, plot, place; voice, perspective, psychology; pace, shape, language; closely observed worlds — both interior and exterior. There’s a reason most of us read novels rather than write them. And that many of those who write novels should be reading them rather than writing them.

To these challenges and perils historical fiction adds its own difficulties. The author needs to be true to the time and setting of their chosen period and not impose the behaviour and values of the age in which they’re writing. But they can’t assume their reader is as familiar with this period as they are having researched it. To create the complete universe fiction demands will mean including detail the world has long forgotten but which was at the time a fundamental part of daily life. How to maintain your reader’s comprehension without destroying the artifice of your novel?

These are not, of course, insurmountable difficulties. One thinks of A Place of Greater Safety and Wolf Hall, and of novels not by Hilary Mantel. Novels by Sarah Waters, Rachel Kushner and Elena Ferrante (for, among other things, Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels are historical ones). Novels by James Ellroy and Don DeLillo. Very different approaches, but all successful.

For every one of those novels, however, there is a Manhattan Beach.

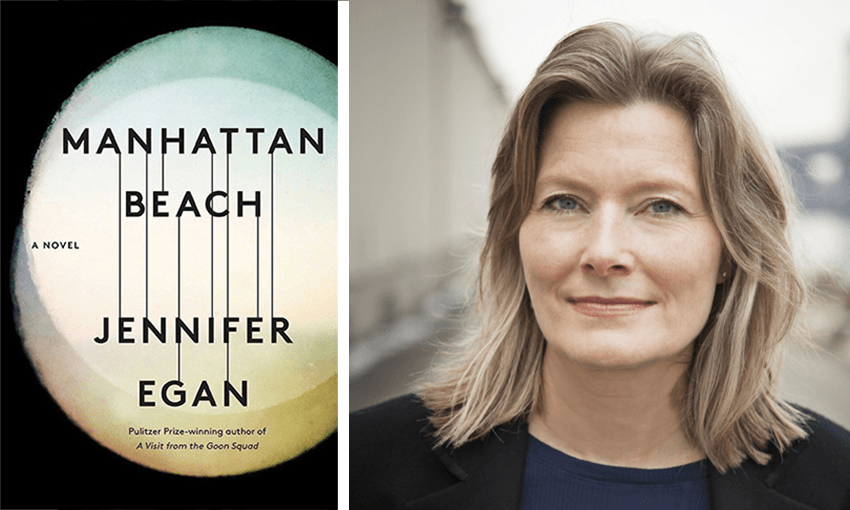

Because it turns out Jennifer Egan is as susceptible to the pitfalls of historical fiction as any other writer. Yes, Jennifer Egan. Author of Pulitzer Prize winner A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010). Of The Keep (2006) and Look at Me (2001). Novels of great verve, intelligence and humour.

A Visit from the Goon Squad is even a novel that deals with history; as was Egan’s first novel, The Invisible Circus (1995), which was set in 1978 and looked back to the political turmoil of the 1960s and 70s. Egan’s handling of that made me hugely hopeful about Manhattan Beach. But the 1960s and 70s are recent history and within 55-year-old Egan’s lifetime. With Manhattan Beach she’s in the 1930s and 40s and World War II. She’s in the library and the archives ploughing through research (as recorded in the novel’s acknowledgements).

Manhattan Beach is the story of three characters and their relationships with each other and other people: Anna Kerrigan, a girl of 11 when the novel begins and a veteran diver in the Brooklyn Navy Yard by the time it ends; her father, Eddie, bagman for a corrupt local union president; and Dexter Styles, a gangster Anna accompanies Eddie to a mysterious meeting with in the novel’s opening chapter.

Dexter lives in Gatsbyesque grandeur in the New York beach resort of the novel’s title, with his well-connected wife and their daughter and sons. Anna and Eddie live in a cramped Brooklyn apartment with Eddie’s wife, a former Ziegfield Folly dancer, and other daughter, severely disabled Lydia.

To say more about the plot would be to spoil what few surprises it holds. Not that these are hard to guess. The novel unfolds with a predetermination born of the hardboiled crime fiction, sea adventure stories and soapy TV mini-series fodder (Irwin Shaw, Herman Wouk; at times one could be forgiven for thinking Barbara Taylor Bradford) whose influence — intended or otherwise — hangs over it. Those and 1930s and ’40s movies, and a post-Sopranos sense of how flawed your male protagonists can be while still retaining the audience’s sympathies.

So playful with form in A Visit from the Goon Squad, Egan here replicates it in dutiful homage, with stock types (blowsy dames with hearts of gold, small-minded and bullying naval officers waiting to be won over) and stock scenarios (dirty-rat betrayals, enmities you just know will end in friendship). However Egan is too good a writer to be entirely undone by the weight of tradition and rounds her archetypes out with more nuance than most.

Although it isn’t exactly pulsing with ideas like A Visit from the Goon Squad and Look at Me, and lacks their sense of momentum and humour, the novel contains perceptive meditations on water and the sea, and their meaning in characters’ lives. It’s also insightful about the relationship between fathers and daughters, and the American capacity for self-(re)invention.

Egan’s eye for detail and powers of description are a match for anyone’s. When Anna sips champagne for the first time, “it crackled down her throat — sweet but with a tinge of bitterness, like a barely perceptible pin inside a cushion”. The sea seen from an airplane porthole is “a sheet of beaten pewter”; a man’s tense face “loosened like a cold roast warming over a flame”.

But, despite these moments, one’s left with the feeling Egan has been charged with a task as taxing as that given Anna when as an initial test before she can become a diver she’s handed a hammer, nails and pieces of wood from which she’s expected to construct a box while underwater.

Egan can’t keep a grip on it all. Her ear for language fails her. She clearly intends the point of view to be close third person, with talk of dames, wops, fruits and “cripple” Lydia’s “prattle”. But then Eddie will have “retched copiously”, Anna will have “demurred” and a lifeboat will have been “commodious”.

“Had she forgotten whom she was talking to?” Dexter says of someone at one point. What was it Calvin Trillin said? “As far as I’m concerned, ‘whom’ is a word that was invented to make everyone sound like a butler.”

When Egan writes that Dexter’s in-laws “were wearing top hats to the opera” while his people “were still copulating behind hay bales in the old land”, it’s a good line, but would be a lot better and more convincing if they were ‘fucking’ not ‘copulating’.

The novel’s starchiest line makes Anna sound like a tenured professor at an Ivy League university as she senses her boss’s sympathy “but the tight aperture of their discourse afforded no channel through which sentiment might flow”.

Language like that has no place in this novel. Language like that has no place in any novel.

Worse than these infelicities (sorry, all that linguistic gentrification is contagious) is that Egan doesn’t know what to do with her research. What she should do with it is something akin to Junot Diaz’s approach to Dominican Spanish in his fiction – never translate, never explain; leave the reader to find their own bearings. To translate and explain is to distance your reader from the narrative you’ve created for them; it places that narrative under a microscope with your reader the detached observer at the end of the lens, whereas they ought to be down there on the slide at the closest possible remove from the action.

Don’t tell me a character is “childless, an oddity in this milieu, where the average man had between four and ten offspring”.

Don’t have a character all but use the phrase “American Century” as though he were Henry Luce in full flow: “We’ll emerge from this war victorious and unscathed, and become bankers to the world. We’ll export our dreams, our language, our culture, our way of life. And it will prove irresistible.”

And don’t have as perfect a detail as sailors hurrying to their gun stations “in their Mae Wests” and then go ruin it by adding “as life vests were affectionately known”.

The result is one viewers of the Netflix series Stranger Things might recognise as the ‘Winona Ryder effect’. Just as you sit nervously every time Ryder hoves into view, waiting for her performance to tip over into bug-eyed, face-twitching mania, so you make your way through even Egan’s finest passages waiting for the moment she can no longer resist shoehorning in another titbit she came across at the New York Public Library.

It’s instructive, perhaps, that one of Manhattan Beach’s best and most engrossing sequences is one featuring characters lost at sea on a raft. Alone, free of any referents to time and place. Adrift from history.

Manhattan Beach by Jennifer Egan (Corsair, $37.99) is available from Unity Books.