Philip Temple reviews a mammoth volume of journals by Landfall founder Charles Brasch – and recalls a harrowing poetry reading which starred a blind man, a Scotsman, and a drunkard.

Charles Brasch is principally remembered for founding Landfall in 1947 and, by editing it for nearly 20 years, his profound influence on the course of New Zealand literature and the arts. He knew everyone in the field who counted, travelling regularly by train, ferry and, unusually for the times, by air to meet writers and artists all over the country. Although a social snob – “that petit bourgeoisie to which the majority of NZers belong” – his judgment of quality has stood the test of time. From the outset he recognised, for example, the native genius of Colin McCahon, James K Baxter and Douglas Lilburn but was more ambivalent about the likes of Allen Curnow and Frank Sargeson. As a private, and therefore unqualified, commentary on most of the writers and artists of the late 1940s and 1950s, his newly published second volume of journals are indispensable for anyone interested in the growth of a distinctly New Zealand culture after the Second World War.

The book was launched at this year’s Dunedin Writers and Readers Festival, at a panel discussion chaired by Peter Simpson, to mark Landfall’s 70th anniversary – the Platinum, no less, with its connotations of rarity, density and malleability. Rare for a literary and arts journal to last that long, one that has often been criticised for the density of its prose and yet one malleable enough to survive the ambitions, quirks and sometimes incapacities of its numerous editors.

The discussion included a reference to Simpson’s attempt 20 years earlier to see through a 250-page “sampler” of extracts from Landfall to mark the journal’s 50th anniversary. The question of whatever happened to that expensive project provoked the only alarum in an otherwise sedate session. Simpson said he still didn’t know why the book never appeared, to which past OUP publisher Wendy Harrex cited incomplete copyright clearances and the death of her father. Posthumous publication had apparently not been an option.

This altercation was minor compared to that which marked the session I chaired in Dunedin to mark Landfall’s 50th in 1997. Golden it was not. The current editor, Chris Price, and publisher OUP had organised commemorative events in the four main centres, and had imported Scots poet and poetry editor for Jonathan Cape, Robin Robertson, as a headline attraction. For his collection A Painted Field, Robertson had just won the Forward Poetry Prize for Best First Collection.

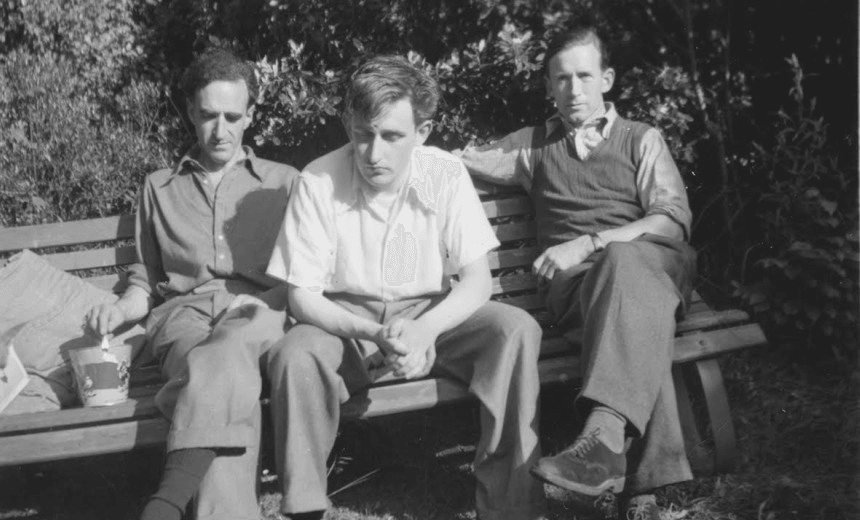

I decided that the best format for the event in Otago Museum’s Hutton Theatre was to have a game of two halves with four of the older contributors to Landfall reading in the first half and four of the newer in the second, ten minutes each max. Robertson would read just before the interval. Although Hone Tuwhare went AWOL, it started off well with Ruth Dallas and John Caselberg sticking to the script. OE “Ted” Middleton then launched on a mixture of history and memoir relating to Landfall and Charles Brasch and perhaps the origins of New Zealand literature.

Middleton, who had been virtually blind for many years, then began reading his own work from sheaves of A3 paper that contained one word each in large type. At the 10-minute mark I rang my little bell which elicited not a page’s pause in Middleton’s peroration. At 15, his partner avoided my imploring look for assistance. Robin Robertson, suffering from jetlag, had gone to sleep. At 20, as the audience grew restless, I got up, took hold of Middleton’s shoulder and asked him to stop. A few minutes later he straightened and apologised for not being given the time to complete everything he had prepared.

Robertson, jolted from his slumber, got up and said that in view of time passing he would read just two or three poems from his winning collection. “Now the night has fallen, Edinburgh comes alight/ as if each building’s shell has a fire inside that burned./ The follies – lit exhibits – stand here on the hill/ in their white stone; the Castle glows”. Robertson paused and someone from the back of the theatre yelled out, “WHO ARE YOU?”

Robertson carried on. ‘”And the streets are bright blurs of sodium/and pearl: the drawn tracery of headlamps/smeared in long exposure. For miles west/the city stretches,/laid with vapour trails and ghosts – ”

Again: “WHO ARE YOU?”

“…to the east, the folding sea has drowned/the girning of the gulls. A lighthouse – ”

Once more: “WHO ARE YOU?”

“…perforates the night: a slow cigarette./Then there is no more light,/and no more breath or sound.”

Except, “WHO ARE YOU?”

Robertson added an extra line to his poem: “WHY DON’T YOU SHUT THE FUCK UP?”

The caller stood up, a local drunken artist, deeply offended at this but was immediately taken in an armlock by his neighbour. As he was marched out he yelled, “WHO THE FUCK ARE YOU?”

For some reason this episode did not make the cut for Robertson’s 2004 book Mortification: Writers’ Stories of Their Public Shame.

*

The first volume of Brasch’s journals, 1938-1945, were published verbatim. But to contain the journals for 1945-1957 within the scope of a similar-sized volume required cutting their 325,000 words – the length of a Middlemarch – down to about 180,000. This demanded of Peter Simpson not only excellent sub-editing skills but also a fine eye for both Brasch’s most memorable writing and the narrative strands that bind together the story of a life and its work. We do not know what Simpson cut out but we have to trust that it was mostly domestic and family trivia or longueurs.

There are broadly four strands to follow: the family; the personal; the cultural, and, perhaps surprisingly, the mountains. For the more general reader, Brasch’s connections with his extended family are of least interest; other than his difficult relationship with his father which was only partially resolved at his deathbed.

Of much more interest is the clear revelation, long obscured, of Brasch’s homosexuality, despite his attachment for a time to Rose Archdall which may be read as an attempt to escape the tortures of his unfulfilled desires, for psychologist Harry Scott in particular. When Scott announced his engagement to Margaret Bennett in November 1949, Brasch wrote, “I cannot help him, he will never need me again, & so I have no place or part in life & no reason to go on living … I felt that my failure in life & final defeat & shame must show in my face & mark me for the outcast I am.”

His attraction to men is punctuated throughout the journals by detailed descriptions of the male physique – which he thought superior to the female. One example is the 150-word description of Noel Ginn who had a face “unusually well-modelled, with small strong chin & small roman nose & clear blue eyes; decidedly a face to notice and admire”. For Brasch, Ginn was the “best example I have met of the noble New Zealander”.

Brasch was constantly tormented and depressed by his failure to establish an enduring relationship. In October 1952 he wrote, “I feel a total & shameful failure as a person, feel as if I were shrinking, shrivelling, hardening physically, slowly poisoning myself; for want, principally … of love given & received – physical and spiritual love”. How far Brasch was able to relieve his physical needs is unclear because many pages were excised by him before he lodged his journals with the Hocken Library; but the implications of this are clear.

He found joy and relief from the stresses of his private life and the increasing burden of editing Landfall by escape to the hills, especially to his beloved Queenstown. In 1946, when international pianist Lili Kraus and her husband Otto Mandl planned to make of Queenstown a “kind of Salzburg or Glyndebourne”, Brasch wrote, “I would prefer it to be kept private, quiet, & for us, not made a tourist town for all the world.” One can be glad that he was spared the current reality.

Brasch undertook long tramping trips with friends: the Routeburn, the Milford Track when the return meant walking through the pitch-dark unfinished road tunnel; a crossing of the Cascade Saddle from the Matukituki to the Dart and Rees valleys: “The magnificence of the Dart Valley, the mountains, & the lake, in this golden calm, is beyond description. It has a spaciousness, a nobility of proportion, that I know nowhere else. One should live here forever, to be filled with the sense of it.” Here was peace for his tortured soul.

After more than a decade back in New Zealand, Brasch returned to England and Europe for nine months in 1957. There was much there that was important to him, such as London’s National Gallery’s “staggering wealth of pictures”. That journal entry is dated March 28, 1957, and it is then that I like to think our paths may have crossed. Aged 18, I was about to emigrate to New Zealand and during my last weeks in London I went to concerts and galleries to listen to favourite music, to see favourite pictures for what seemed like the last time. Did we stand together at the National Gallery as I looked again at the painting that meant most to me, Turner’s “Rain, Steam and Speed”?

When he returned at the end of that year, Brasch could write of New Zealand that it was “richly various, with much packed into little, with grandeur and great distances, more than enough to enjoy for a lifetime, large enough for a people and a civilization”. Through those same mountains I was soon to learn the truth of that, too.

Charles Brasch: Journals 1945-1957 edited by Peter Simpson (Otago University Press, $59.95) is available at Unity Books.