Margo White reviews the greatest novel ever written from the point of view of an opinionated and somewhat pompous foetus – Nutshell, by Ian McEwan.

We might as well start with the novel’s memorable opening sentence: “So here I am, upside down in a woman.” Ian McEwan has said the sentence came to him when he was sitting through a dull meeting and looking for mental distraction, out of which came Nutshell, a 200-page Shakespearean soliloquy narrated by a foetus.

It’s a very opinionated, erudite, sardonic, literary, poetic and a somewhat pompous foetus. If the reader is wondering how he could know so much when he hasn’t even been born, “not even born yesterday”, the foetus puts it down to listening to a lot of radio, news on the half hour, analysis, the BBC World Service, and podcasts and audio books such as “Know your Wine” and Ulysses. Yes, it’s a daft explanation, and there are several times in the book in which McEwan provides utterly unconvincing explanations on how this not quite omniscient narrator could possibly know what he does. But then McEwan has also described the book as a conceit, and it’s best read as such.

The foetus’ particular vantage point allows him to eavesdrop on the conversations around him, like that of his mother Trudy, who is plotting with her lover and brother-in-law, Claude, to murder the foetus’ father, John. In this refashioning of Hamlet, something rotten is going on a “not very united kingdom”, or more precisely, in a neglected Georgian inner-city London pile worth millions. The epigraph and the book’s title come from the same play: “Oh God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space — were it not that I have bad dreams.”

His mother sends her unborn child turning and tumbling on Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Noir, and if he’s lucky, Sancerre, his preferred drop. When she declines the third glass, he takes it as evidence of her love for him, but frustrated by her discretion. “That’s when I have it in mind to reach for my oily cord, as one might a velvet rope in a well-staffed country house, and pull sharply for service. What ho! Another round here for us friends!”

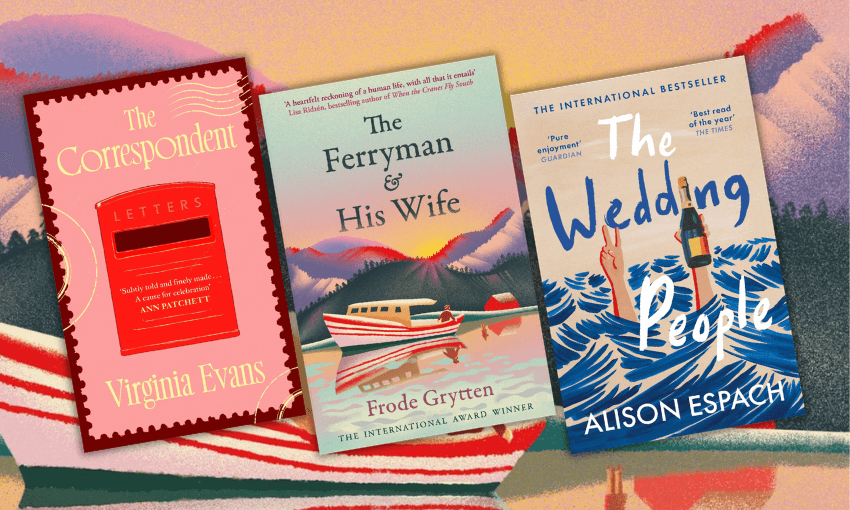

LIVE ACTION SHOT OF THE NARRATOR OF IAN McEWAN’S NOVEL

Increasingly the foetus would rather be somewhere else, particularly when Claude comes to visit, a property developer who torments him with his vulgarities, his clichés, the way he whistles ringtones and washes his private parts in the same basin his mother washes her face. And often gets too close for comfort. “Not everyone knows what it is to have your father’s rival’s penis inches from your nose,” he laments, bracing himself against the vigors of his mother’s lover. “This turbulence would shake the wings off a Boeing … On each occasion, on every piston stroke, I dread that he’ll break through and shaft my soft-boned skull and seed my thoughts with his essence, with the teeming cream of his banality. Then, brain-damaged, I’ll think and speak like him. I’ll be the son of Claude.”

It shouldn’t be like this, he fulminates; he should spending his third trimester in a suspended state of bliss, with nothing to worry about except growing big enough to be born, not living inside a story and fretting about its outcome. He becomes increasingly melancholy. The radio talks and podcasts that once moved him seem “more like hot air”.

But he can’t do much from his en-wombed position other than kicking against his fate, which he does, using his heels rather than his boneless toes. At one point he imagines he’ll get his revenge by being born, by making his mother fall in love with him, thereby displacing his uncle. “I’ll bind her with this slimy rope, press-gang her on my birthday with one groggy, newborn stare, one lonesome seagull wail to harpoon her heart. Then, indentured by strong-armed love to become my constant nurse, her freedom but a retreating homeland shore, Trudy will be mine, not Claude’s …” Later he wonders if it would be better not to be, if he could use his umbilical cord as a noose.

There are, unsurprisingly, several literary and Shakespearean references. “She thinks I protest too much,” says the foetus’s father, John. “So we’ll stick our courage to the screwing whatever,” says his brother, the less poetic Claude. At one stage Trudy cleans the house in shorts and pink-framed heart-shaped sunglasses, which is possibly a nod to Nabakov’s Lolita; the foetal voice has echoes of Humbert Humbert.

You know how the murder plot is likely to end, but McEwan draws us in, with the novel gathering suspense and momentum. The foetus only has access to partial truths; he can’t see anything or anyone, and is left to pull things together from muffled voices (ears pressed against “the bloody walls”) and shifts in tone, or by drawing conclusions from other information, such as changes in his mother’s pulse rate and blood pressure. But things are incomplete; is his father a hapless well-intentioned poet, or someone more Machiavellian? Is Claude not so dim-witted after all? And what about Trudy — is she actually planning to dump her unborn son in foster care, or is she playing one brother against the other? Can and will the foetus do anything about any of it?

The story might be wrapped around an unbelievable narrator, but then we bought Metamorphosis, narrated by a giant insect, didn’t we? Nutshell is a very clever flight of fancy, and it’s a lot of fun.

Nutshell (Jonathan Cape, $38) by Ian McEwan is available at Unity Books.