Letters to Hone Tūwhare and his Travelling Band of Constant Companions, continued.

Read more from the lockdown letters here.

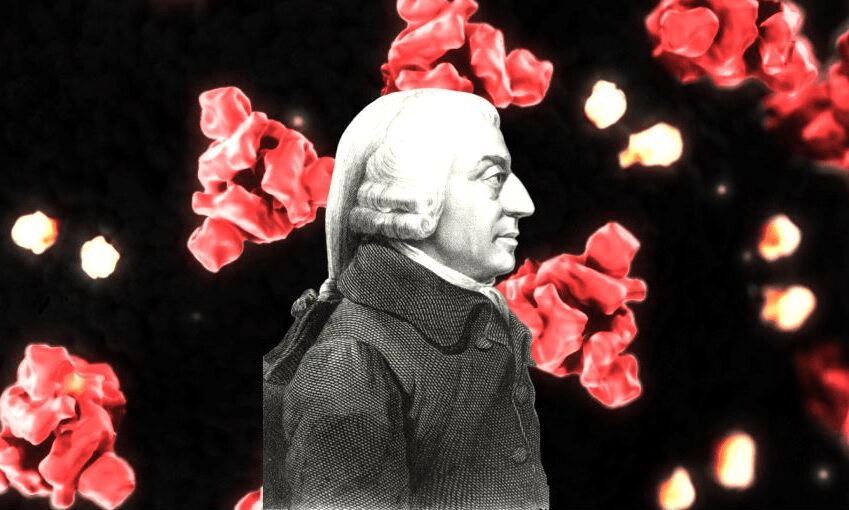

Dear Adam Smith,

Jesus, brother. You’re a long way from home. We don’t get many economists passing through here. But that’s no reason not to drop in of course. As it happens you might just be in the right place at the right time. People are talking about economies right now. Think ours could have broken down in the middle of the road. I’m not really sure what one is to be honest. Some sort of machine perhaps. Where one thing leads to another. A wheel turned by an invisible hand. That’s what I’ve heard anyway. We’re full of invisible hand at the moment, brother. If that’s anything to go by. This one is a virus though. Pokes at the spokes. Sends us inside. Makes us question what we reach for. Value. Looks like one invisible hand is giving the finger to the other at the moment. So if you don’t mind rolling up your sleeves, and happen to have a spanner on you, we could use you right now.

Do you remember when we drove past that accident? Not you and I of course. I just expect the dead to see everything. I was with Aunty Kare and Ruthie. We were heading back to Hamilton from Te Tii. Ages ago. Just out of Kawakawa. Not far from the turn off to Mōtatau. Talking shit. And laughing. We were at the top of the long rise. Where the road starts to dip and weave. We came around the bend and saw that van on the other side of the road crunched around a tree. You couldn’t miss the people in the front seat. Rescuers working on them. There was nowhere else to turn. We could see their faces. Hear the screaming. I’ll never forget it. We just shut up. Straight away. No more laughing. Bullshitting. We were witness to the chasm. Sent a shiver through us I don’t mind saying. Rejigged our sense of value. Reminded us that we are animals at the end of the day. Beautiful, frail, temporary. And panting.

No one spoke for an hour. We drove slowly. Kept our distance. Let people cut in. Pull out. Waved. Were kind. I don’t know when it happened. Days later maybe. A week. But sooner or later my speed crept back up. After a month I found myself sitting at the wheel snarling, “For fuck’s sake,” at someone. I was back to a kind of forgetting. Being a prick.

You can see it happening here now. We are back to the niggling. Crawling out from our hiding places and saying, “That wasn’t so bad.” Second guessing. Banging on about doing it differently if we had another chance. Comparing ourselves. It’s kind of beautiful in a way. Reassuring. Tender. Watching the healing. Like when a cut fades to an itch. Quite a few of our stubby fingered sulkers are out. Scratching their crayons back and forth. “I was really brave, Mummy,” they say. “I was only trying my third best.” But it doesn’t work for me. I’m still looking at colleagues in London. New York. Listening to the screaming in the van.

I’d love you to meet my mum. She’s little. Eighty this month. Has taken a walk around the block every afternoon for years. Five kilometres. Waves out to neighbours. Stops to talk to a few locals. When she was a kid the headmaster at Ōtāhuhu College took time to visit her parents and tell them she should go to Uni. She got a job as a typist instead. Met my dad. Had four children. Wore a bikini at church picnics. Made us curried sausages. Mince pies. Stopped us kicking each other under the table. Then boiled the shit out of cabbage and potatoes. She was never not there for us. Ever. Made a choice to live in our shadows. Like some great unseen heartbeat. You could call her an invisible hand.

When my dad was falling to pieces, my mum got up two to three times a night to look after him. For years. He would roll out of bed. Strand himself in a tangle of blankets and sheets. She would be Sisyphus. And he would be the rock. She visited him afterwards too. When the time came. Six days a week in his dementia unit. She still grows a garden. Knits for people. Hats for babies at our clinic. Mows the lawns. Takes the bus. Saves her money. Spends it on us and the grandkids. When she was in her fifties she had breast cancer. Got it again a decade later. Then thyroid cancer. Had two lots of radiotherapy. Parts of her lung twist and knot like gorse now. It makes them hard to clear at times. And ripe for bugs.

I have a sister who teaches young people to play the piano. A small city of students have grown up in her kindness. The other is a minister. Listens to heartache most days. My brother studied science. Worked in finance in Sydney and New York. Has impossibly good-looking children. I write poems. Listen to kids. Am wounded by them every day. We all love in our own way. Strobe out into our communities. And everything that we pass on. Every last comfort and care. Comes from my mother. Who is probably knitting hats right now. Or out walking around the block. Getting home by herself. And making sure she watches the weather.

My mum has probably never shown up in the GDP. Men can be pretty shit with a tape measure when it comes to women. No offence. But she could help you with that. Run it down your arm. Around the cuff. Calculate costs in an instant. Show you where you went wrong. Pins askew in her mouth.

I’m not sure how long you’re about for. Or just how far you’re allowed to stroll away from this beach. But there’s a few dreams I’d love you to wander into for me if you can. People are up in the middle of the night. Plumbers. Sparkies. Builders. House-painters. Restaurant workers too. Hairdressers. Pilots. Stewardesses. People who run tours and things. Hotels. Dairies. Butchers. I’d like to think you can help them. Have their backs. Go through the books with them. Get that wheel turning. More than anything else I’d like you to thank them for me. From the bottom of my heart. They’ve been our doctors. More than anyone else during this thing. If their heads slump into their hands. And they start to wonder what it was all for. Tell them that they saved my mother’s life. That they are good. And that I can’t begin to thank them.

Tell them I’ll make them curried sausages if they want. And to bring me their kids when they’re crook. I know where they can get a woollen hat as well. Especially going into winter. If I can flick them some work, stay with them for a night or two, go for a feed at their place, I will. Leave them a tip. I reckon there’s a heap of us who feel the same way. I don’t mind living in a country that’s driven past a car crash for a while. At least till we get to Hamilton. It’s about those invisible hands again at the end of the day.

Doctors are full of doubt. We learn early. And we learn hard. Mine sits on my shoulder like a parrot now. It’s a noisy bloody companion most days. But I wouldn’t go anywhere without it. So maybe if you could tell those people running the country right now that we know they’re only one chapter ahead. And that that’s ok. Tell them it’s always shit trying to guess our way through this stuff. But it’s just the way it is sometimes. And we get it. Tell them to keep doing their best that’s all. Test each thought. Be honest. Stay with us. Keep us in the loop. The sea is stormy and rough. But we need to get to the other side.

For what it’s worth tell them they’ve been pretty bloody steady too. And we’re grateful. And to be kind to themselves. Listen lots. Read up. Ask. Put us all together and we’re a pretty clever bunch. And tough. Don’t let them forget that they’re not alone. Tell them there are a hell of a lot of dead people walking up and down the coast who have seen it all before too. They can wander down here anytime. Have a yarn.

I don’t know if you’ve ever heard a mōteatea, brother. A longing. I’m not really too sure how you value them. Or if they show up in the GDP at all. But I wrote one for my mum a while back. It’s about opportunity costs if you like. Women’s work. The wealth of nations. But mainly it’s about my mum. I can’t sing it for you on a piece of paper. But beaches are always good for a tune. Listen to the wind. The gulls. The drone of the surf. Anything invisible you can get your hands on. You’ll get the idea.

Good to talk, brother. You’re not as scary as I thought. I’ve heard you were close to your mum too. Maybe that’s why. Thanks for the yarn. I hope you go well out there. You’re welcome back here anytime. Underneath our big old sky.

Te kākano kāore i ruia

Waiata au mō te kākano kāore ano i ruia.

Waiata au mō te kākano kāore ano i tipu.

Waiata mō tōna tūmanako.

Waiata mō te kanehe.

Waiata ki te pakiaka tanumia mai i te onemata ki tua ē.

Waiata au ki te whānako kāore ano i mau.

Te ara rā kāore tōku whaea i whiria.

Te ara rā kāore tōku whaea i hīkoi.

The seed not sown

I sing for the seed not sown,

the seed unsprung,

the one my mother did not water,

the one my mother did not sow.

I sing for its anger untangled.

I sing for its roar unexplored.

I sing for its roots, generations deep

in the warm damp earth.

I sing for its stem indivisible.

I sing for the hunger.

I sing for the art.

Her dark red heart.

Her dark red heart.

I sing for the seed not sown,

the thief uncaught,

the road my mother did not travel,

the path my mother did not walk.