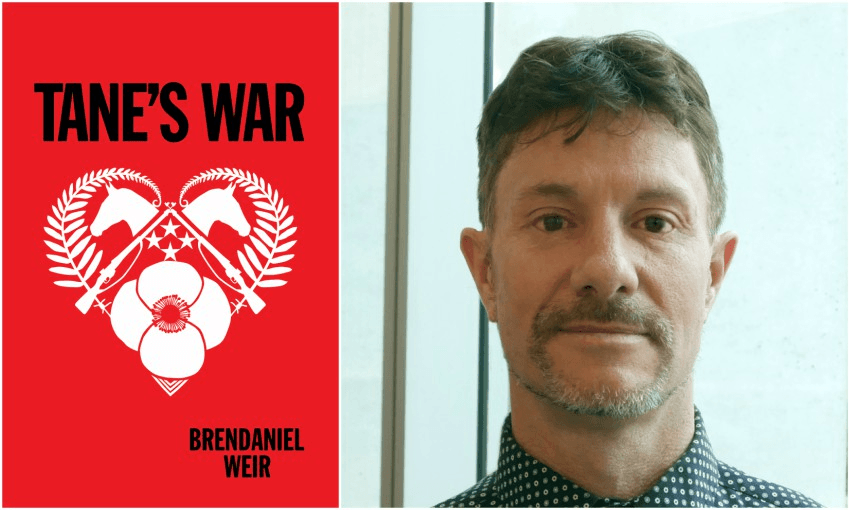

Brendaniel Weir backgrounds his novel of a gay affair between Pākehā and Māori lovers.

My first love was a Māori man. Let’s call him Wiremu. I was 16. He was several years older than me and a whole world more experienced. I can hear the knee-jerk reaction of people reaching for the paedophile/abuser label but let me be clear that the connection was consensual and largely driven by me. It lasted six months before Wiremu ended it. I was heartbroken as only a spurned teen can be. It was not until later I realised how much I had learned, how much I had grown because of that connection. Wiremu introduced me to the gay community that became my family when I found myself homeless a few months later. He taught me the importance of safe sex at a time when HIV/AIDS was only just emerging, and condoms were not widely used. He taught me that my body was my own and how to say no.

But it wasn’t just sexuality I explored with Wiremu. I had been raised in a conservative white neighbourhood during the late 70s and early 80s, an environment that provided few opportunities (or motivation) to broaden my cultural understanding. Beyond a couple of Māori songs we sung at school, I had no comprehension of Māori culture. It was Wiremu who opened my eyes to the real New Zealand I was living in – a bicultural nation full of diversity and colour but dominated by narratives of the rightness of “white” culture (often through the misrepresentation of Māori).

Elements of that first relationship and of Wiremu became bound up in the character of Tane in my new novel Tane’s War. But there was another force at work in his creation. I made an authorial decision to use Tane’s Māori heritage, along with all the ingrained racism of the historical settings, to create a parallel narrative about marginalisation.

And as I wrote Tane, I found myself drawing on my own experience of exclusion and disempowerment to give him substance. While one form of marginalisation doesn’t give an author automatic insight into another, it does disrupt the safety of privilege. I was using something real to discover who he was, how his past and his environment might have defined him. Working across boundaries is invariably imperfect; forms of marginalisation are never identical. The clearest example of this in my book is the way gay characters can hide their sexuality – decide whether to live open or closeted lives. There is a harsher reality for Tane who cannot choose to hide his race.

Should Pākehā writers be able to write Māori characters? That’s a complex question for which I have no easy answer. But I can speak to why I decided it was okay to write Tane. I began by asking myself, “Why am I creating a Māori protagonist?” I’m a Pākehā male. While my sexuality sets me apart and gives me an understanding of the struggles of minorities, I harbour no doubt that I was born into a culture of lingering colonial entitlement. I worried that creating the character of Tane could be an act of cultural appropriation.

Our literary past is full of Māori functioning as costumery, as backdrop or exotic colour to white-centred stories. More recently I’ve noticed characters of different ethnicities being used by writers to signal their “awareness” of diversity or to appeal to a wider audience (a process that invariably props up existing prejudices).

A similar force is at play for LGBT representations. At a time when there are more gay characters in mainstream media than ever, writers, filmmakers and networks cling to outdated stereotypes and seldom create gay lead characters. I want to see writers representing my identity with respect and consideration – and ideally with the same passion they pour into their straight characters. I could do no less for Tane.

The seed of Tane’s story was planted in my head in 2002 as I listened to an old man, Clarry, recount a tale of first love – a memory passed down three generations in whispers and nods. When Clarry was young he had an affair with an older man who, in turn had discovered his own truth in the arms of a World War 1 veteran. The picture of this ex-soldier was vague, as is often the case for oral histories that have been hidden for reasons of safety. For years I tried to imagine how the soldier had lived his life. He risked everything for a country that called him a criminal or wanted to forget him. When he returned was it to a hero’s welcome? Did he grow bitter leading a hidden life? Was he lonely or did he find fulfilment? His shape haunted me for almost a decade until I finally decided to write him out.

I began by trying to name him, a search that was frustrating and ultimately fruitless. Clarry passed away in 2004 and his few surviving contemporaries could only offer echoes of the original story. The man was lost – to me anyway. For a more general picture, I looked to archives. An Awfully Big Adventure edited by Jane Tolerton (which I heartily recommend) led me to the World War One Oral History Archive. There I discovered only five references to homosexuality – three denials of its existence, and two referring to it as a filthy Turkish habit.

I was lucky enough to speak to Chris Brickell, author of Mates & lovers: A history of gay New Zealand, who explained the way contributions of gay military personnel have been erased from our histories. Families fearing dishonour would, more often than not, destroy personal records that might implicate their sons or brothers. Institutions, powerful individuals and even historians have been known to erase or alter histories to realign them with “existing values”.

With no further detail available to me, the character I was writing had to be fleshed out entirely from my imagination. So I drew from my own experience.

Tane’s War by Brendaniel Weir (Cloud Ink Press, $29.95) is available at Unity Books.