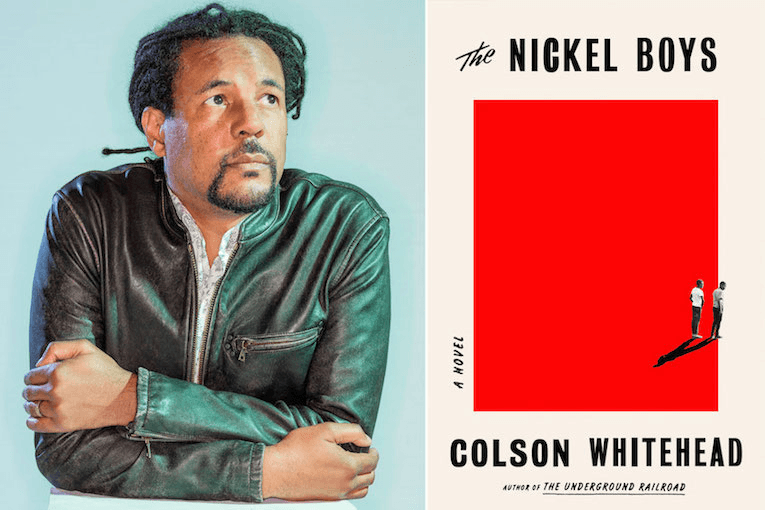

Colson Whitehead won the 2017 Pultizer Prize for Fiction for The Underground Railroad, a depiction of slavery and resistance in 19th century Georgia. Now he’s back with a similarly grim premise, following two boys through the horrors of a real-life reform school in Florida. Our reviewer is Aaron Smale, whose reporting on similar schools in New Zealand led to a Royal Commission of Inquiry.

There is something depressingly familiar when reading about an industrial or reformatory school. It doesn’t matter what period, what country, what group of people the school is aimed at, the culture and behaviour within such schools is uncannily the same.

Mostly this familiarity emerges in the turgid prose of reports from government inquiries, using language that might hint at the awfulness of those institutions. But such reports never quite get at the feel and taste and embodiment of what it was like to be there.

The Nickel Boys breaks down that perceptual barrier by rendering in elegant and musical prose the experiences of a group of kids who attended the Florida School for Boys. The institution was a real one, and Colson Whitehead’s fictional portrayal brings it to disturbing life.

The story is based around Elwood, a studious but naïve African-American kid growing up in the 1950s and 60s in Tallahassee, Florida. Another character, Turner, is his friend but somewhat opposite in temperament, more street-wise and skeptical.

Elwood’s character and internal and external worlds are fully developed before the reform school even makes an unannounced appearance. His growing awareness of his home situation and the parents that abandoned him to the care of his grandmother runs parallel to the segregated society that confronts him as a black adolescent. The ferment of the civil rights movement is woven through the narrative without being heavy-handed.

His strict and protective grandmother limits the cultural influences he is exposed to but if there is a soundtrack to his coming of age it is a record of the sermons of Martin Luther King Jr. If anything, the ideals he hears in the sonorous exhortations of the preacher put him at more risk, as he dutifully tries to live up to the hope the messages hold out to him.

His aspirations take a cruel turn when he is hitch-hiking to free college classes and instead finds himself in the clutches of a completely different institution – the Nickel Academy.

The realisation of what awaits him only slowly dawns on Elwood and the reader. The presentable façade of the buildings gives way to the discovery of neglect and squalor. The matter-of-fact communications from staff give way to cynicism and abuse. The uncertain silence of the other boys gives way to a petty and irrational violence and cruelty that confounds Elwood’s moral view of the universe. Invisible, brutal hierarchies permeate daily existence, with the black students firmly rooted at the bottom.

The descriptions of the abuse and violence are rarely explicit. The subject is usually approached from a more oblique angle where the reader is given just enough detail to imagine the worst without actually being told what happened next, before skipping on to the next indignity. It mirrors the silence that the boys learn to cloak their suffering in.

But the seriousness of what is going on is foreshadowed in the opening chapter where the story starts in the future discovery of the remains of boys that are unaccounted for. This sets up a foreboding that hangs over the story. Who was in those unmarked graves? How did they get there? Which of the characters meet their demise?

The story progresses inexorably down a dark road that conjures up a sense of dread, even when the writing has a buoyant air. The later chapters are interspersed with some featuring the characters as adults. So they’ve made it out the other side, but at what cost? Who got left behind and how? The writer skillfully propels the narrative forward with these hints and clues.

If the physical and psychological details of the writing are utterly convincing, there is also a running interpretation of that experience by the characters and narrator that speak to the big themes. In one internal reflection, a character ponders how: “It didn’t stop when you got out. Bend you all kind of ways until you were unfit for straight life, good and twisted by the time you left.”

The body count rises, at first with anonymous characters who don’t get any time on stage before starting on secondary characters whose unsympathetic qualities make the reader’s sympathies ambivalent. But then death starts stalking one of the central characters. A clever bait and switch leaves the anticipated ending in tatters. Instead, something more complex emerges.

Nickel Boys is an elegiac piece of writing that remembers what authorities are often determined to forget – institutions that damage and destroy young lives and pass on an inheritance of harm. Those kinds of bricks and mortar institutions may have passed into history, but the harm continues to haunt generations. Unfortunately it also provides cover for state authorities, in jurisdictions around the world, to intervene in yet more harmful ways.

Nickel Boys, by Colson Whitehead (Hachette, $34.99) is available at Unity Books.