Sam Brooks raves about Michelle Rahurahu’s debut novel, Poorhara.

There are two signs of a great novel, for me. One is that I can’t stop reading it, and absolutely must blast through it in one sitting. Those are the kinds of novels that envelop you in a voice, in a world, in the vision of the author, and to break free of that space feels like a violation of the reader’s contract. For a few blessed hours, I am under an author’s spell and there’s nowhere I’d rather be.

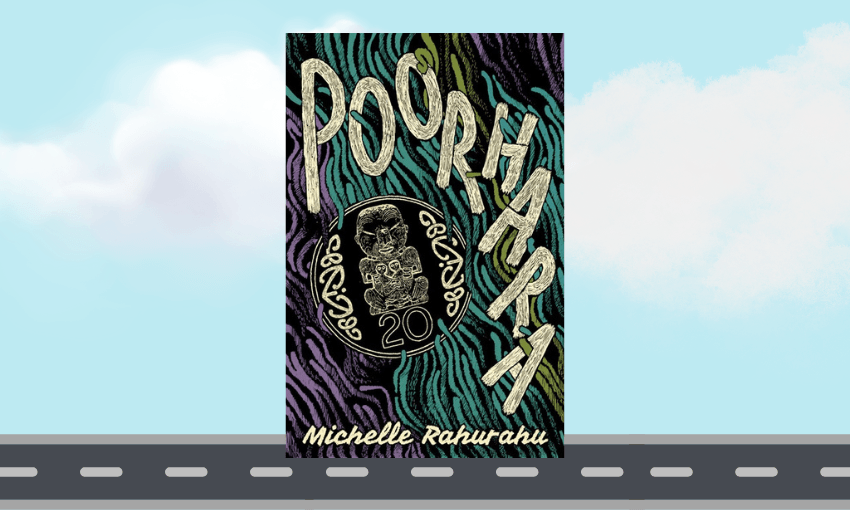

The other sign is a novel that earns taking space away from it. The kind of novel where it feels like not an invention of the author, but that the author is tearing down a veil between the reader and a part of the world that they hadn’t considered, or worse, ignored. Claire Baylis’ Dice, from last year, was that novel for me. Michelle Rahurahu’s debut novel Poorhara is another.

One part family drama, one part harrowing road trip, Poorhara follows two young cousins, Erin and Star (Whetu). Erin has left high school to help her aunty clean houses, while also taking care of the family that sprawls in and out of her household. Star, drifting through university, is home for the first time in years and feeling completely out of his depth in the house he grew up in. As the family drama escalates, the pair find themselves in the confines of a 1994 Daihatsu Mira, with a nameless dog, bouncing from place to place and person to person.

Rahurahu’s debut is billed as a tragicomedy, and that label is apt. Poorhara is, in a fleet 300-and-change pages, rife with violence, racism on every level, poverty and aggressions that span the spectrum from micro to macro. She does not shy away from the fact that her two protagonists, and their whānau, are stuck in a country – if not a land – that makes their existence harder at every turn. Be it BayCorp, be it the bevy of local cops they encounter, be it even the supposedly kind bartender down at the local pub. There is every reason for them to scream and flail against the world, and very often they do, because it is the logical thing to do.

However, they also laugh. They make jokes. They cling together. Once there’s no water left for tears, no words left for screams, all you can do is laugh. Most of the comedy in Poorhara comes less from the characters being funny – although they have the expected in-jokes and familiarity that you might expect from cousins – and more from Rahurahu’s omniscience. Take this passage, from early on, where Star is trying to chat to a girl in line for the toilet about the infamous drunk uncle anti-drinking ad (which, bleakly, could be one of many):

“He’d really spun a yarn, insisting it was the funniest thing, waxing philosophical about bureaucracy’s lame attempt at showing the hard-hitting effects of drinking, before inevitably diving into his classic colonisation rant. All rivers lead to the sea.”

Elsewhere in the novel, Rahurahu drops the kinds of observations that hit like a truck; things the reader absolutely knows to be true the moment they finish the sentence and wonders why they haven’t thought of that phrasing before (in this instance, the “they” might be “me”). Star’s irritation at his whānau, for one: “The only prize he’d gotten for being the so-called favourite was a feeling that he was always being watched.” And Erin considering the stories she’s growing up with, for another: “A lot of the stories she learned as a kid had a problem being solved by someone offering a piece of themselves – literally. Usually that person was a waa.”

Poorhara is tragedy in the expected sense of the word; nothing that happens to these characters is their own fault, but the fault of a colonialist, racist society that they have to navigate with a shoddy map and misleading directions.

But it is also a comedy in the purest sense of the word. Not necessarily in that it is laugh out loud funny – although it often is – but in that what Erin and Star have to go through to simply exist in the world, not even thrive in it, is so absurdly unfair that the only response is to laugh. (It is, in this fashion, of course, an accurate reflection of Aotearoa.)

This is also, without belabouring the point, a Māori story. Erin and Star are in bodies, and lineages, that will never let them forget they are Māori. In very different ways, both characters are finding some sense of security in their identity, while also finding their place in the world. Rahurahu’s sense of place is fantastic; the whanau home feels as real as a community library the cousins find themselves in later in the story. There is also elegance here – she has a way of framing spaces that other writers would render ugly or insignificant with a softer eye.

There is a line to be drawn between Poorhara and Greta and Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly; both are novels with two protagonists that aim for a deeper, more poignant view of what it means to be part of a family, part of a community, part of society. Where Greta and Valdin felt light (though still profound), Rahurahu takes what could otherwise be a heavy story told in a depressing world, and gives it the grace and love that it deserves. Her characters and the world they inhabit are viewed through such a humanist lens that it never feels too heavy enough.

I stopped about two thirds through Poorhara to take a walk. It wasn’t because the novel was too much or too heavy – Rahurahu has a spy novelist’s mastery of knowing how to amp up the tension of certain movements to keep the reader enthralled, and then slowly letting the air out. Instead, it was that I wanted Poorhara, I wanted Star and Erin, to take up more space in my brain. I wanted to think about them more, I wanted to consider them more, I wanted to imagine around them more.

That, for me, is the indicator of a great novel. In just 300 pages, following two cousins in a car, Michelle Rahurahu tells the story of a nation in conflict, a deeply disparate society, and a family surviving through it. It is as honest a portrait of Aotearoa as I’ve read all year, and am likely to for many years.

Poorhara by Michelle Rahurahu ($38, Te Herenga Waka University Press) is available to purchase from Unity Books. This review was originally published on Sam Brooks’ newsletter, Dramatic Pause.