Mary Macpherson talks to a brilliant Texan photographer who makes portraits of men and the land in the disappearing American West.

In the bulging shelves of our photobook collection, there’s a select area reserved for the most significant and deeply loved works. One of these books is a tall slim volume with a metal spine and austere brown/grey cover offering little clue to its contents.

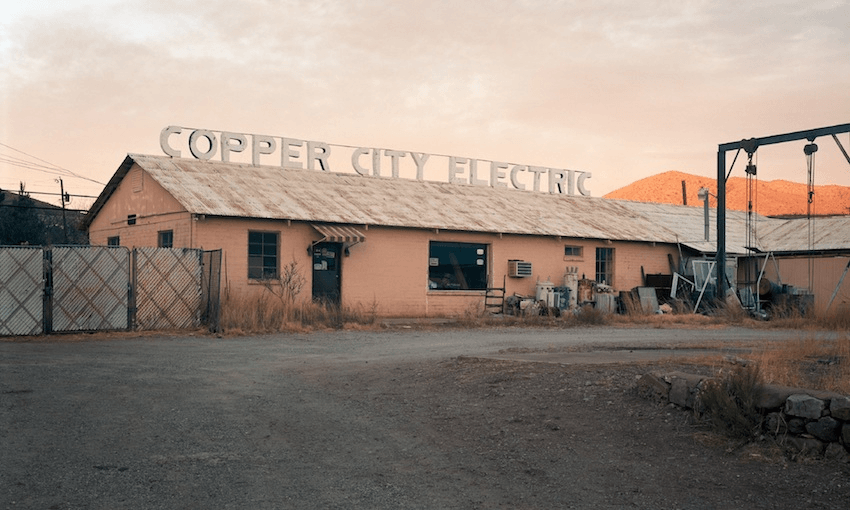

Grays the Mountain Sends by Texas photographer Bryan Schutmaat opens to a portrait of the people, interiors and scarred landscapes of hard-scrabble mining towns in the American West. It speaks to dreams of decaying Western majesty with images and sequencing full of bittersweet poetry. It’s a book that’s been lauded worldwide, won numerous awards, and been internationally acclaimed as one of the best photobooks of 2013. In March, he’ll be appearing at the Photobook New Zealand, Wellington’s biennial photobook festival.

I recently talked to Schutmaat about Grays and his new work Good Goddamn, depicting the last days of freedom for a man in rural Texas before he goes to prison.

What drew you to start photographing in the mining towns and small communities of the American West?

For as long as I can remember I’ve been intrigued by the American West, mainly because of the landscape and its grandeur. The region is just filled with places where I love to be – vast expanses, big mountains, big skies – and when I first got into photography, I took sporadic road trips “out west” to shoot. After some time engaging with the land and making pictures without any real human presence, I began observing the people living in all those small, faded towns that the dot the West – people who actually call the place home. I got inspired and made vague plans to do a project about the blue collar West, but it wasn’t until I visited a worn-out copper town called Butte, Montana that anything really materialized.

Butte ignited my creative energy. I fell in love with its history, its surfaces, its hardness, its sorrow, etc. There was so much potential there. I began shooting there with the intention to make a body of work that was just about Butte, yet out of curiosity and a kind of compulsion, I began exploring other nearby mining towns, and I ultimately decided to expand the geographic reach of the project to areas all across the American West, the result being Grays the Mountain Sends.

It takes its title from a line in the Richard Hugo poem ‘Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg’. Sarah Bradley in PhotoEye has written, “Grays doesn’t feel like a photobook, it feels like poetry.” What do you take from poetry in creating your images and photobooks?

Poetry is one of the many forms of art that inspires me to create. When I first read Richard Hugo, for instance, I was deeply moved. I loved the content, style, and deep sentiment. I then felt an immediate urge to make work that might have the same kind of atmosphere and emotional resonance. That’s really what I strive for; I want my work to be emotive and lyrical, so I approach photography in a literary way, and often it’s poetry that’s my guide in trying to achieve that aim.

The Hugo poem about decline and spoiled dreams has a similar atmosphere to the towns and landscapes you photographed in the Rocky Mountains. Were you inspired by the poem before you did the work, or did you find it later?

I discovered Richard Hugo’s poetry while I was shooting the project, but it was pretty early on in the process, so I was able to move forth and make most the photos with his work in mind. I feel like Hugo’s ghost was my co-pilot.

Is the last photograph of the only woman in the book a nod to the red haired waitress in the last line of the Hugo poem?

Yeah, I totally stole that from Richard Hugo. It’s also an homage to one of William Eggleston’s photos. I wanted my ending to have a little bit of hope in the form of a woman.

What inspired your latest book Good Goddamn?

Kris, the subject of the book, was the inspiration. I met him a few years ago after my parents bought property near his family’s farm. I just love his presence, and I always wanted to photograph him. When he told me he might be going to prison, I knew I had to do the project, and I knew I had a short time to complete the shooting because his court hearing was impending. I shot the photos in just a matter of days.

Where does the title come from?

I can’t remember the context. I think we were drunk. But “good goddamn” was just something I heard Kris exclaim one time.

Both Grays and Good Goddamn focus on blue collar men in the landscape. In Grays there’s a sense of a failed dream of Western majesty. In Good Goddamn the man uses his last days of freedom in the outdoors. What interests you about men and the land?

I don’t mean to sound too obvious or simplistic, but I think that at the core I just find both subjects very beautiful. I enjoy photographing men and their characteristics, especially if they’re rugged and scruffy or have a certain style that interests or appeals me. The landscape is also beautiful and there’s no question as to why it’s alluring, however I mostly focus on land that’s not traditionally attractive. I photograph places that have been worn down or depleted in some way by industry and human activity. I’ve tended to be more interested in what people do to the land than the land itself.

Kris, the subject of Good Goddamn, was essentially saying goodbye to the land and the nature he grew up around and had known all his whole life. That country made him who he was. He knew the trees, the hills, and the stars at night, yet he was headed for a prison cell, so a sadness permeated as he spent time hunting and being in the woods with the knowledge that the years ahead of him would so starkly differ; his expressions of freedom and engaging with that landscape would be distant memories.

More broadly, when considering men and what they do in the land and to the land, an impression of masculinity emerges, and I think masculinity might be my most fundamental interest in both Grays and Good Goddamn. For most of human history, masculinity, strength, and a man’s sense of worth and goodness was demonstrated through a prowess in relation to the landscape, whether that’s hunting, farming, felling timber, or finding precious metal in the ground. Pride and social capital has belonged to men who can best demonstrate masculine exploits within the land and wilderness.

Do you think in America that the abundance and promise of the land has been squandered?

Yes, I do think that to a large degree the United States is endowed with vast resources, but they have always tended to provide wealth to only those at the top. Most ordinary people in America don’t get a fair shot at success because their socioeconomic statuses hold them back from the start, and income inequality continues to grow. Plus, the environment has been ceaselessly abused, polluted, overgrazed, depleted of water, and so on. Industry and agriculture have horribly scarred the country. I actually just read a piece in the New York Times about the American West which quoted William Kittredge, whose work was an inspiration for Grays. They used the following quote: “We have taken the West for about all it has to give. We have lived like children, taking and taking for generations, and now the childhood is over.”

Both your books are notable for an absence of words. Do you think words get in the way of photographic narratives?

Yes, I generally think that words get in the way of photos, at least for my work. The photos create a world of their own, and too much text or caption information impairs that world for the viewer and takes away mystery. I just like to put a general description of the work as whole rather than individual captions, and I don’t think I’d ever have an academic style essay in one of my books. If there’s writing, it should be a work of art like the pictures.

Are you planning to photograph in New Zealand while you are here? If you are, is there anything you are particularly looking for?

Yes, I plan to take a bunch of travel photos with the camera on my phone. I don’t think I could make serious work or do a place like New Zealand much justice in the short amount of time I’ll be there, but perhaps I’ll return one day.

All photographs are from Grays the Mountain Sends by Bryan Schutmaat. He will be giving a public lecture at Te Papa on Saturday 10 March.

The Spinoff Review of Books is proudly brought to you by Unity Books.