Kind of, argues Sam Brooks. And he’s here for it.

I made it through all 720 pages of A Little Life before I realised that Hanya Yanagihara was not, in fact, a gay man. It might’ve been the cover image – a man’s face contorted in pain. It might’ve been the fact that the book depicts friendship between gay men with such fine detail and an uncomfortable intimacy. Or, honestly, it might’ve been because I couldn’t imagine why someone who is not a gay man would want to write about gay men.

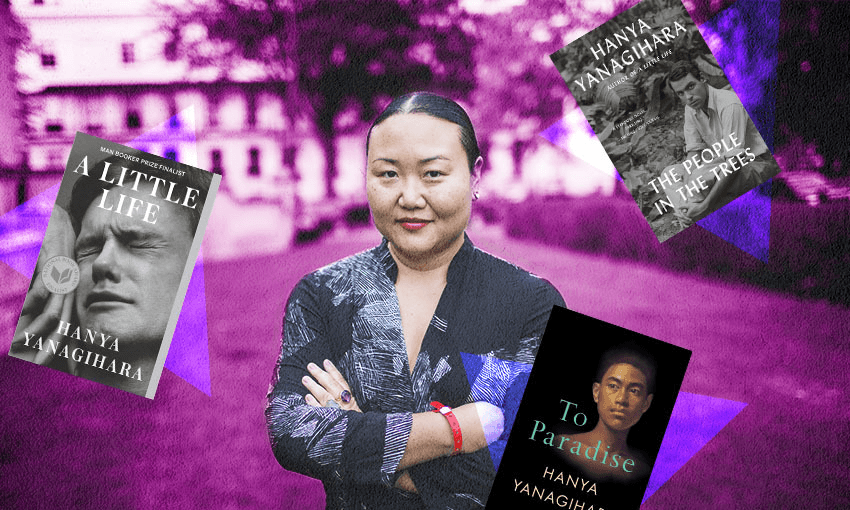

Yanagihara, as you probably know by now, is not a gay man and never has been. She is a 47-year-old heterosexual Hawaiian woman, who has worked as an editor for several New York media publications (right now she’s at T, the style supplement to the New York Times.)

I’ve come to think of her as the epitome of a fruit fly, an affectionate but also fairly shady name for a woman who finds her company amongst queer men. In all three of her novels – The People in the Trees, the aforementioned A Little Life, and the recently released To Paradise – she almost exclusively writes about lives of gay (or queer-coded) men, at length. This is an aspect that has variously bewildered, repulsed and fascinated readers.

She addressed it directly in a New Yorker profile earlier this year: “I don’t think there’s anything inherent to the gay-male identity that interests me.” I’m not sure how convincing this is; writers generally don’t write novels about topics that don’t interest them. More convincingly, in an interview with Kirkus Reviews, she said that men are given such a small emotional palette to work with. “I think they have a very hard time still naming what it is to be scared or vulnerable or afraid, and it’s not just that they can’t talk about it – it’s that they can’t sometimes even identify what they’re feeling.”

Her most fascinating response to this question, and one that veers ever so close to entitlement, is in an interview with the Guardian: “I have the right to write about whatever I want. The only thing a reader can judge is whether I have done so well.”

And judge they have: A Little Life, a phenomenon on its release in 2015, has vocal fans and vocal detractors (and probably a larger contingent of people who think it is just fine). Nevertheless, it won Yanagihara a boatload of awards, and it has since been adapted into an opera, a deeply appropriate form for the length, breadth and depth of the source material.

To Paradise, a collection of three lightly connected riffs on Henry James’ Washington Square (the first being the most explicit) seems to have had a cooler response, as you might expect from a Henry James riff in 2022. The People in the Trees, the first and least of her works, is an aggressively upsetting novel told from the point of view of a paedophilic scientist investigating a South Pacific tribe, and would likely be torn apart by the extremely online of 2022.

I’m not especially interested in the ethics or the morals of Yanagihara writing about gay men, to be honest. I firmly believe any writer can write anything, but the writer must also understand that an audience can respond however they want. As a gay man, I find her work authentic. The next gay man you talk to might find it offensive. The one after that probably hasn’t heard of her. There is no yardstick for authenticity.

At any rate, writing a piece of fiction isn’t taking a selfie, it’s taking a photo. Yanagihara flags this in the same New Yorker interview: “If I were putting on my dime-store-psychologist hat, I would say more that it’s easier, freer, and safer to write about your own feelings as an outsider when cloaked in the identity of a different kind of outsider.”

It’s first nature for a reader in 2022 to assume that a writer’s skill at writing a character comes down to certain personal attributes rather than a level of craft, technique and observation that allows them to capture the life essence of somebody else. Yet the way you frame a subject says as much about you, and how you live in the world, as your subject of choice does. So it’s Yanagihara’s lens that interests me, and why she points it the way she does.

A Yanagihara novel is like the person at the party who tells you everything when you first meet – either you’re drawn in by their charm, their ability to tell a story, their ability to see into you, or they fail all those checks and you walk away. (If you looked at A Little Life, that dumbbell with a crying man on the front, and expected a fun romp, I worry for your observational abilities.)

Yanagihara’s novels are dense, slow and lumbering things. The worlds are intricately built, and the relationships inside them don’t move by chapters, but by full acts. They are lush and overly detailed.

What strikes me most about Yanagihara’s work is that it doesn’t read like the kind of high-minded, award-winning literary fiction that gets reviewed by fancy publications.

No, it reads like fanfiction.

Before I unpack that, it’s important to stress one point: distinguishing fanfiction from literary fiction says nothing about fanfiction, and says everything about the mainstream perception of fanfiction being less important, or of a lower quality than literary fiction. Terrible literary fiction exists, terrible fanfiction exists. Great fanfiction exists, great fiction exists.

It is generally understood that most fanfiction writers are women (as high as 80% for popular fanfic site AO3). A significant proportion of fanfiction is slash fiction, a genre that focuses on romantic or sexual relationships between people of the same sex – and a significant proportion of that genre focuses on gay men.

(It’s worth noting the gendered approach to Yanagihara regarding her books’ length and detail, too. A Franzen novel could kill a man, and not just out of boredom.)

On slashfic, Katherine Dee from The New Spectator writes: “Surveys of slashfic also show that it is an inherently feminine expression of erotica. Slash emphasises themes like nurturing, bonding (often telepathic), and intense, lifelong commitment.” Sound familiar, Yanagihara readers?

A Little Life is essentially a gender-flipped version of Mary McCarthy’s 1963 novel The Group, reimagined as a hurt-comfort fic, a popular genre of fanfiction where one character takes care of another suffering a trauma, as in the final section of To Paradise. Hell, the first section of To Paradise is literally a version of James’ Washington Square set in an alternate history version of New York where same sex marriage is not just allowed, but common.

It’s not just her subjects that align Yanagihara with the fanfiction genre, however.

The work of hers that feels most like fanfiction, outside of the rather crude labels applied above, is her first work, The People in the Trees. The novel was inspired by the truly horrible story of David Carleton Gajdusek, a revered scientist and academic who was later accused of, and imprisoned for, child molestation.

Stylistically, it’s the most audacious and difficult of her novels – a high bar to clear. The novel is largely made up of the fictional memoirs of Dr Abraham Norton Perina, written while he is in prison, and the bulk of those memoirs involve an anthropological study he is involved with, investigating the fictional U’ivu tribe.

These memoirs are framed by notes and edits from Dr Ronald Kubonera, a protege of Perina’s, and his unsolicited footnotes form the novel’s fascinating tension. He doesn’t believe Perina committed the crimes he has been convicted of, and refuses to let the bad doctor include in his memoir things that may incriminate him further.

Being inside Perina’s mind, who is at bare minimum a sociopathic misanthropist, but more realistically, a complete monster, is an unpleasant time. It’s only Yanagihara’s craft, and her near fetishistic interest in developing the fictional tribe and island of U’ivu that keep us reading. I could read this sentence a thousand times over:

“Beautiful people make even those of us who proudly consider ourselves unmoved by another’s appearance dumb with admiration and fear and delight, and struck by the profound, enervating awareness of how inadequate we are, how nothing, not intelligence or education or money, can usurp or overpower or deny beauty.”

Another aspect that this, and all her work, shares with fanfiction is a contract of understanding: I am giving you this, but under no circumstances do you have to keep reading. You signed up for this, for these pages-long descriptions, the one sentence every 100 pages that hits you right in the gut, the languid stroll towards a conclusion. You can get out at any time. It’s the overtalker at the party energy, coming out strong.

What sets Yanagihara’s fetishistic lens apart is that each book is a world of her own making, containing characters of her own devising. That’s because, with the exception of maybe the two central characters of The People in the Trees, Yanagihara has a deep love for her characters – the kind of love that is more common in fanfic than in literary fiction. You write about these characters because something made you love them, rather than creating characters to then make them miserable, like a sociopathic child playing with toys.

Amongst the trauma parades of A Little Life, it’s easy to forget that these are characters who are highly accomplished, deeply beloved, constantly throwing fancy parties in opulent apartments with high walls. She devotes nearly half of the second act of To Paradise to a lush, albeit sad, party. She creates these people, and she might make them sad, because that’s what drama dictates, but at least they’re in designer clothes.

What makes this most interesting, and even audacious, is that Yanagihara has crossed over into genuine literary acclaim and success while not deviating from the fanfic playbook. She writes about men who love other men. She puts those men into long, heavy stories about their feelings. She creates worlds that drip with intense, specific detail.

And she doesn’t apologise for any of it.

To Paradise, by Hanya Yanagihara (Picador, $38) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.