Poet Jenny Rockwell on how a new wave of artists offered her a way to celebrate queerness.

I am 16 years old and perched on my single bed, Tumblr open on my secondhand MacBook, ‘Sweater Weather’ blasting through my janky, glitter-wire headphones. I am trawling the web, desperately trying to find a happy lesbian love story. If there is a queer film or TV character they are more often than not doomed to a life of secrecy, ostracism and heartbreak, and are killed off at an incredible rate (five times higher than non-queer characters!). The Top 20 pop chart for the year 2014 had no openly queer artists, and outside of niche gay YouTubers, the only openly lesbian person in the mainstream spotlight seemed to be Ellen (I know). While Catholic school taught me that to be anything but straight was to be a hellbound-harlot, the queer representation (or lack of) had me convinced that not only would I burn in the sulphur lake of the afterlife (among the weeping and gnashing of teeth), I would be eternally miserable while alive, as well.

Fast forward to 2024: the year of queer joy. JoJo Siwa claims to have invented gay pop (although we know its rise stems back before even Prince and David Bowie), and Kehlani, Boygenius, Janelle Monáe, Reneé Rapp, MUNA, There’s A Tuesday, Omar Apollo, Ethel Cain, Troye Sivan, Fletcher, Girl In Red, Lil Nas X and Chappell Roan are rapidly on the rise. Chappell Roan belts ‘Good Luck, Babe!’, an upbeat, camp-esque song about refusing compulsory heteronormativity to an audience of 150,000 people at the Governors Ball, and nonchalantly quotes drag star Sasha Colby on Jimmy Fallon. Janelle Monáe comes out as non-binary. Three couples get engaged at the same Girl In Red concert. Kehlani posts TikToks about loving being a lesbian to their 6.6 million followers. Billie Eilish, the female artist with the most monthly listeners in the world (as of this month) releases Lunch, unashamedly celebrating lesbian sexuality, and Troye Sivan’s ‘Rush’ becomes an IT clubbing song of the summer. Not only are these artists writing hit songs about love and sex and identity, they are offering us a glimpse into a queer existence no longer so stale and stereotypical and, well, depressing.

It feels a lifetime ago that it was near impossible to find a single LGBTQIA+ artist to look up to. What impact does this visibility in the mainstream have on the radio-listening trucker driving home on SH1, or the blood-nosed teen in Tirau, chipping off their painted nails? Or me, all those years ago, desperate for something to suggest I would be OK?

To me, queer joy is something that I had to claw my way up through the dirt for. The first time I felt it was at the first queer club night I attended, ironically called Church. I’d freshly come out to myself but I lied to my friends about what I was doing that Friday, hastily dodging their questions. I was 24 years old and still so afraid of myself.

I arrived at the venue shaking. The hole-in-the-wall club was down a dark graffiti-smattered set of stairs, ripped tour posters glued messily one over another, disappearing into the underworld. I silently scanned my ticket, head bowed, avoiding eye contact with the butch lesbian smoking at the entrance. Turning the corner into the basement-esque club, my vision adjusted to what looked like heaven: a few hundred sweating bodies, shining with glitter in the neon lights, shaved heads and tattooed arms and swaying limbs; holy. Dancing and voguing and drinking and kissing and laughing and talking and screaming and existing. It was the distinct moment in my life where I realised, viscerally and for the first time, that I was not alone. That all those nights spent begging god to fix me were perhaps more communal an experience than I had realised. While I cried myself to sleep, desperate to wake up straight, all across the world, across different time zones and small towns and cluttered bedrooms, other people prayed the same prayer with me. We just hadn’t found each other yet.

So here I was, on the night of my awakening. And it felt good. To dance in the thick crowd, to be blinded by the smoke machine and the vape clouds, surrounded in baggy pants and sports bras and armpit hair, high heels and heavy makeup and mini skirts, to the backdrop of drag queens glowing on the janky platform stage. To look around at a room full of people who not only choose themselves, no matter how difficult it is, but also have the audacity to feel joy? A truly divine thing. I had thought maybe if I tried really hard, one day I could come out and face a life of pain and suffering and anguish, but at least I would be free to be myself. And all of a sudden, looking around this cramped, sweaty room, I was faced with the overwhelming reality of joy.

These days, I feel this joy when I see two elderly men clutching onto one another on an afternoon stroll down Ponsonby Road, so rare to see with the horrors they survived, how no one stares. How it must feel for them, to be able to live a simple, quiet life with one another, to tend their garden with their muddy hands. To sit on their porch, watching young passersby screech and dance their way down to the clubs, the boys in skirts with bold pink eyeliner, the girls with sharp gems on their crooked teeth. I feel it when my girlfriend and I see a couple walking down the street, and we squeeze each other’s hands tight, hoping they see us. We get so damn excited, just to see a reflection of ourselves, laughing how they might feel the same way seeing us. I feel queer joy when I take a moment to look around at the community I have now, and remember how I built it, brick by shaky brick, moulding this life for myself with the same hands I once thought dirty.

Of course, our community continues to suffer so deeply, particularly those with intersectional identities, like takatāpui, QTBIPOC and our gender-diverse whānau. Queer joy doesn’t seek to ignore the horrors our community withstands, or pretend those very present struggles don’t continue to exist. Legislative attacks and anti-LGBTQIA+ bills continue to threaten our right to exist, queer rights vary drastically across countries, and many in our communities’ lives are at risk every single day. Queer joy does not seek to ignore this. It offers that we do the work, the activism and the protesting and the support systems and the pushing for a world where we can exist equal, and that we hold each other hard at the end of each day. Queer joy acknowledges the pain, the hurt and the struggle, and dares that we dance together to ‘Pink Pony Club’ in spite of it. Because to be joyous in a world that is constantly trying to erase you? Perhaps the most powerful revolution of all.

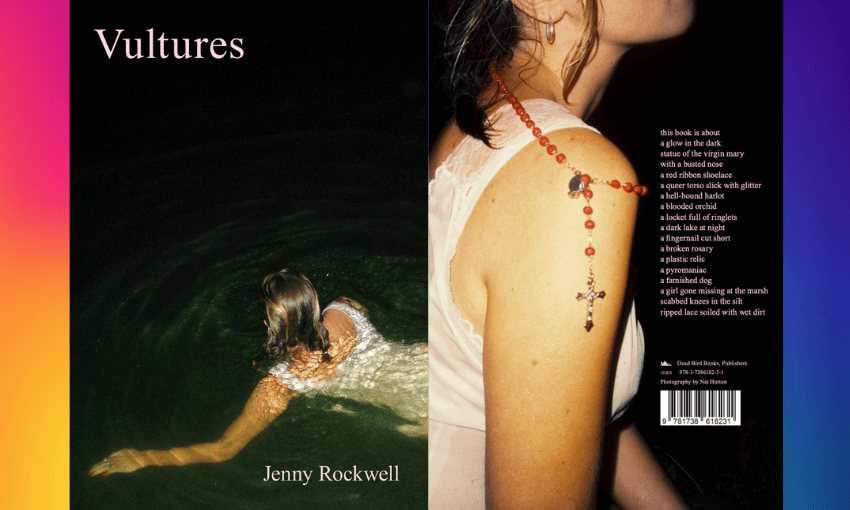

Vultures by Jenny Rockwell ($30, Dead Bird Books) is available from Unity Books.