Danyl Mclauchlan examines the latest work of one of the most famous public intellectuals in the world.

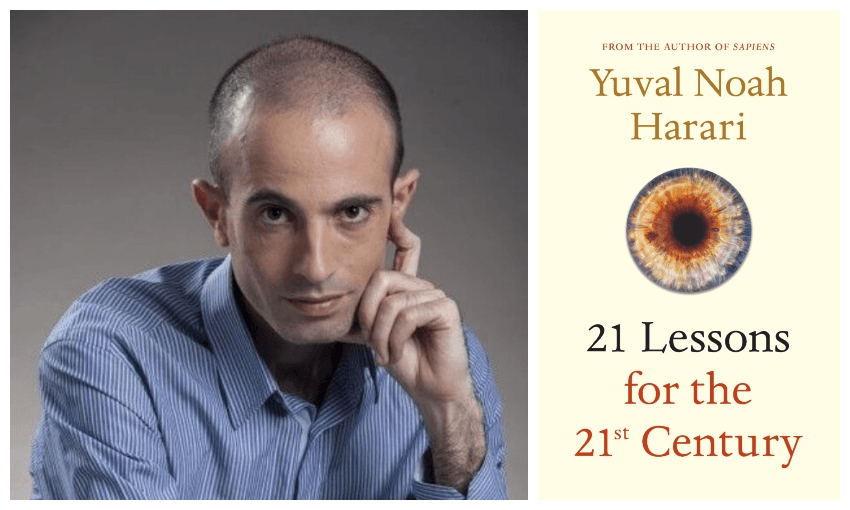

Five years ago, Yuval Noah Harari was a humble academic, quietly lecturing at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem where he specialised in medieval history. In 2014 his fourth book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind – originally published in Hebrew – was translated into English and in a very short space of time, Harari became one of the most famous public intellectuals in the world, ascending into the Davos-sphere, blurbed by Bill Gates and Barack Obama, and his profile and sales numbers dwarfing those of popular soi-distant thinkers like Jordan Peterson or Mark Manson.

If you’ve somehow missed Harari’s omnipresence in the bestseller lists, the TED talks, his op-eds in the mainstream media: his books, essays and talks function as intellectual mixtapes, synthesising a wide range of ideas from across the humanities and social and natural sciences, especially evolutionary psychology and philosophical postmodernism. They’re delivered through witty little aphorisms and catchy phrases, all delivered in Harari’s wry, detached voice which, even though the books are footnoted, kind-of implies that many of these brilliant ideas are the author’s unique insights, but also that these often highly speculative theories are established, indisputable facts.

It’s easy to see why he’s so successful. Harari is the most lucid and effective communicator of challenging ideas since Bertrand Russell. With a vast supply of historical anecdotes to illustrate points which might be drawn from postcolonial studies or orthodox Judaism or molecular biology or feminist theory or computer science, Harari is here to explain the world. Or, at least in his latest book, explain why it cannot be explained.

His grand narrative of everything goes like this: humans are a species of primate; we’ve existed in our current anatomically modern form for about 300,000 years. Our brains and the moral and social intuitions wired into them are designed by natural selection to help us live and flourish as members of small bands of apes competing for resources in the scarce and dangerous environment of East Africa. We weren’t the only members of the Homo species: 100,000 years ago there were many different subspecies of humans scattered around the world: the Neanderthals, Homo Erectus; that “hobbit” species they found fossils of in Indonesia.

But about 70,000 years ago our subspecies went through a “cognitive revolution”, causing a change in the wiring of our brains, bringing us to what anthropologists call behavioural modernity. This allowed our minds to form more complex ideas and – crucially, for Harari’s narrative – to form ideas about things that do not exist: it allowed us to tell stories, and form mythologies, religions and ideologies.

With our expanded linguistic capabilities we were able to gossip about who should be the next leader, who would make a good mate, what was the best plan to hunt game, and invent fictions that explained the world. We formed larger, more coordinated groups and moved from the mid-point of the food chain to the apex, quickly expanding across the rest of the planet, exterminating all of the other human species and almost all of the large animals, or megafauna in the world as we went (eventually arriving in New Zealand, the last major landmass to be settled, in about 1200 AD, where we wiped out the megafauna and 60% of all bird species in less than two centuries).

Even though we don’t live in small nomadic bands any more, our genes and brains are still optimised for the environment we evolved in – which is why so many people feel such a deep sense of alienation and disorientation towards the modern world; we’re not designed to live in vast cities or technologically advanced societies.

But the alienated state of modernity is a comparatively good deal, Harari argues, pointing out that all societies that existed between the agricultural revolution 11,000 years ago and the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries were characterised by regular famines, lethal epidemics, horrific violence and constant warfare; they were societies in which the ruthlessly exploited masses were ruled over by tiny castes of rapacious elites: a third of children died before adulthood; average life expectancy was somewhere between thirty and forty. Now more people die from overeating than famine, from old age than plague, and warfare is virtually non-existent.

How did we get to modernity? By building ever more elaborate narratives allowing humans to organise together in larger societies that could then attack neighbouring groups and assimilate, enslave or exterminate them. As we coalesced into bigger groups with more specialised division of labour we built cities and kingdoms and empires; along the way we invented new cultural technologies that allowed even more complex societies, and these inevitably enslaved, assimilated or exterminated their neighbours.

The most important of these cultural technologies, Harari claims, were literacy, legal systems, “universal religions” like Buddhism, Christianity and Islam, and money. Money is “the most successful story ever told by humans” and “the most universal and most efficient system of mutual trust ever devised”. These innovations – still just fictional narratives – were capable of amalgamating huge numbers of diverse peoples into single markets united by money, imperial orders united by bureaucratic legal structures and congregations united by faith.

Five hundred years ago most of the population of the world lived in religiously defined, despotic commercial empires. Europe was a small, fragmented, insignificant region on the periphery of the vast Ottoman Empire, far from the political and economic powerhouses of China and India.

But then the civilisations of Northern Europe developed scientific rationalism and capitalism, two astonishingly powerful and highly complimentary cultural technologies, and they deployed them in the traditional sapiens manner, expanding, enslaving and exterminating; seizing control of as much of the planet as they could. This lead to the “transformation of the world” beginning in the 18th century: the merger of all the separate empires and scattered tribes into a global civilisation of nation-states connected via a global capitalist economy powered by modern technology.

And we’re now at the end-point of that process. During the 19th and 20th century organised religion lost its intellectual relevance, discredited by rationalism. The ideologies of liberalism, fascism and communism emerged as rival narratives but after the spectacular rise and fall of communism and fascism, only liberalism – the ideology most compatible with rationalism and capitalism – survived as a credible value system.

Now liberalism is failing too, its core doctrine of individual rationality and free will utterly discredited by findings in psychology and behavioural economics, its global markets and democratic processes powerless to prevent the accelerating destruction of the planetary ecosystem or reverse the trend of increasing inequality across the developed world.

Nor does the liberal system or its institutions have anything to say about the looming threats of artificial intelligence and biotechnology, either or both of which will lead to the creation of greater-than-human intelligence: a new form of life which will treat us, Harari predicts with grim relish, with the same compassion we treat the animals we farm and slaughter, or the other human species we exterminated in our conquest of the planet.

Harari’s books all make the same points, albeit in different ways. Sapiens is a history of our species which ends with his predictions about the future; Homo Deus is “a history of the future”, much of which talks about the prior history of our species; 21 Lessons is structured as a series of essays, each dealing with contemporary issues and their “deeper meaning”.

Each book reaches the same conclusions: humans are primates, violent yet social animals designed to live in the stone age and overwhelmed by modernity, our minds are algorithmic, almost everything we believe is a socially constructed fiction, technological progress may soon lead to the obsolescence of our species. We’re apes; we’re storytellers; we’re algorithms; we’re doomed.

So what are our current problems and their “deep meanings”? Deep problem # 1: our major threats are global, confronting our entire species but almost all of our institutions and intuitions about ourselves are local. We see ourselves as individuals or citizens of nation-states, or adherents to some religious or political faith, or members of some identity group competing against our rivals for resources and status. We should, Harari feels, see ourselves as members of a single species who must collaborate to solve a series of existential crisis.

Second deep problem. There’s no credible narrative, no story we can all agree on to make sense of the world. Scientific explanations of reality are too convoluted for anyone but a tiny handful of academic elites. The global economy and its interactions with technology and culture and politics are too complex for any human to fathom; no model or theory approximates it, which means it cannot be directed or controlled.

The response to this has primarily been one of intellectual nostalgia. The failure of liberalism leads people to religious conservatism, or nationalism, or communism: but these are all just forms of nihilism; they have no actual solutions, just an irrational belief that if you get rid of that ideologies’ bugbear – trade, or multiculturalism, or secularism or capitalism – you’ll magically solve everything.

Third – really – deep problem. We don’t understand ourselves. We cling to discredited notions of the human condition and think we’re beings with immortal souls, or members of some group with unique qualities, or rational individuals with free will. None of these stories are true.

Our response to the world we find ourselves in, Harari concludes, should be one of humility and open bewilderment. Instead of adhering to old certainties or established narratives we should learn to think critically, to out seek new ideas, new ways of living and relating to each other. But to do this, we need to know more about ourselves and who we really are.

So how do we, like, discover who we really are? Yuval Noah Harari is glad you asked. In the final two chapters of 21 Lessons for the 21st Century he stops talking about Stalin and the Lascaux cave paintings and industrial farming and the Meiji Restoration and The Lion King and Aldous Huxley and Assyrian military tactics and Mark Zuckerberg, and talks about his own life and beliefs.

Harari was a troubled and restless teenager who pondered the meaning of life and wondered why there was so much suffering in the world. He thought he’d find the answers in academic study or philosophical inquiry, but was frustrated to find that neither of these paths seemed to yield any real insights.

Then, when he was a 24-year-old doctoral student at Oxford, one of Harari’s friends convinced him to attend a ten day long meditation retreat. The experience changed his life. He was taught vipassana meditation by S N Goenka, one of the pioneers of the secular meditation movement, sometimes characterised as a protestant version of Buddhism; a non-mystical interpretation of the religion stripped of gods, demons, afterlives, reincarnation, Bodhisattvas flying around illuminating people and other such trappings and focused on the praxis of meditation. A sign outside Goekna’s office famously read “Please avoid theoretical and philosophical discussions and focus your questions on matters relating to your actual practise.”

Since then Harari has meditated for two hours every day, and he spends one month a year at a retreat, meditating intensely. This isn’t about escaping reality, he insists: it’s about getting in touch with reality. Meditation, he writes, gives him the detached perspective with which he writes his books, and revealed to him the truth behind the fundamental teachings of Buddhism: that everything is impermanent; all existence is suffering; the self does not exist.

Meditation and Buddhism are not panaceas, Harari admits. Meditation is simply too difficult for most people and – because none of his essays seem complete without a description of some historical atrocity – he recounts various wars and genocides carried out by devout Buddhists. But it is the path he’s found, and its the path he recommends to his readers after three books debunking every other religion, system of belief or ideology ever conceived.

We’re addicted to stories, Harari concludes; they’re our greatest invention but the truth about reality, he announces in his final essay, is that there is no story. It’s a paradoxical but probably inevitable lesson for one of the most persuasive and influential storytellers in the world to end on.

21 Lessons for the 21st Century by Yuval Noah Harari (Jonathan Cape, $38) is available at Unity Book