The massive new roading project only opened this week, but one group has already been reaping the benefits for years, writes Bernard Hickey.

This is an edited version of a post first published on Bernard Hickey’s newsletter The Kākā.

Early on Wednesday morning I drove from my home in Wellington north to Paekakariki to attend the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the 27 km-long Transmission Gully roading project. PM Jacinda Ardern, finance minister Grant Robertson and transport minister Michael Wood were there, as were a couple of hundred other dignitaries including local iwi leaders and former MPs.

You may wonder why so many were so intensely focused on this one project.

If you’ve not lived in Wellington, you might be surprised by the apparent obsession with what seems like just another road, albeit a particularly big and expensive one.

But this is not just another road to Wellingtonians. It has been a dream for 103 years, we at the ceremony were told by the PM, referencing a 1919 call by a local MP for a new faster road from Paekakariki to the capital. There’s even a much-believed (but not proven) myth that US Marines offered to build the motorway in 1942 to move troops between Wellington Harbour and their training camps on the Kāpiti Coast. Over 15,000 practised their Pacific Island landings there during World War Two.

For many Wellingtonians, for at least a couple of decades, a new road out of the city has offered a pathway to a brighter future. It has become the region’s proxy for “progress”, a type of cipher to identify who you were and what you wanted. Wellingtonians mired in cold winds and overcast days dream of driving up the coast to calmer and sunnier and flatter climes. Owning a bach on the Kāpiti Coast or Horowhenua, or moving your parents into a retirement unit there, is an indicator of wealth, progress and a “better life”.

If only you could drive there faster and more safely, and then get back again without being stuck in a Sunday-night queue for hours while driving into the gloom of Wellington. If only you could live on the coast and commute easily to the city for work.

If only…

Transmission Gully is the project Wellingtonians have been dreaming of and scheming about for as long as I can remember. One of the first conversations I had when I started as the Dominions Post’s business editor in 2003 was with then editor Tim Pankhurst, who told me it was one of the paper’s main campaigns.

So much hoping and planning and spending and working for an 11-minute time saving. Transmission Gully was a political-life-long ambition for Ohariu MP Peter Dunne, who included it in his 2002 and 2005 supply and confidence agreements with the Labour-led government, and his 2008 agreement with the new National government.

Days before the announcement of the date for the 2014 election, then transport minister Gerry Brownlee trumpeted the NZTA’s signing of the public private partnership deal with Wellington Gateway Partnership, a consortium of CPB-HEB Consruction and Ventia, which are controlled by Spain’s CIMIC, to build the motorway and then operate it for 25 years. The private funders included ACC and the global InfraRed Capital Partners.

Eleven minutes costing $1.25b in today’s money

The deal was designed so the government, which was trying to get its post-quake and post-GFC debt down, didn’t have to borrow money from 2014-2020 to pay to build the road.

When first agreed in July 2014, the “net present cost” to the government was estimated at $850m. NZTA said at the time this was $25m less than using the usual non-PPP procurement and maintenance methods.

Here’s then NZTA CEO Geoff Dangerfield, at the time of the deal, saying the Transmission Gully PPP would provide the best value for money and the most certainty of delivery:

“Not only do we have certainty that the project will be built to a strict deadline that will see it opening in 2020, but the PPP contract also requires that the project is designed, constructed, operated and maintained to achieve a high standard of performance in the areas of safety, journey times, reliability, and customer satisfaction.” .

Since then though, disputes and cost overruns linked to earthquakes, bad weather, Covid and various design and construction problems and delays have seen the net present cost rise to $1.25b. That means annual payments of at least $180m, although the exact final cost or annual amounts haven’t been disclosed yet.

Over $200m has already been paid to the consortium to compensate for the extra costs and ensure the delays were “only” two years. An initial review of the PPP process for Transmission Gully done last year found it was consented on a non-PPP basis and therefore was also going to see cost overruns, and the original budget set for it was too skimpy. The Infrastructure Commission is doing a bigger formal review, now that the road is finished and open.

Eleven minutes worth billions in today’s wealth

The road will save motorists an average of 11 minutes for the trip between the CBD and the Kāpiti Coast, and in theory reduce each driver’s petrol usage by even more due to more efficient engine performance at higher speeds and on straighter roads. However, carbon emissions may be substantially more in net terms because the motorway is expected to encourage more people to drive the route because it will be faster and safer, and because fewer people are expected to use public transport.

The PM talked on Wednesday about the productivity benefits from the road with (in theory) more people spending less time travelling and instead working or relaxing. It certainly will make trucks and their drivers more productive per hour worked and litre of diesel burnt. Those benefits will accrue to the trucking companies in higher profits, and/or lower transport prices than would otherwise be the case.

But the biggest crystallisation of the societal benefits of Transmission Gully is in land values.

Boom time on the Coast

Real estate agents and land owners on the Kāpiti Coast and Horowhenua have been the most aware of how these benefits are pumped into land values.

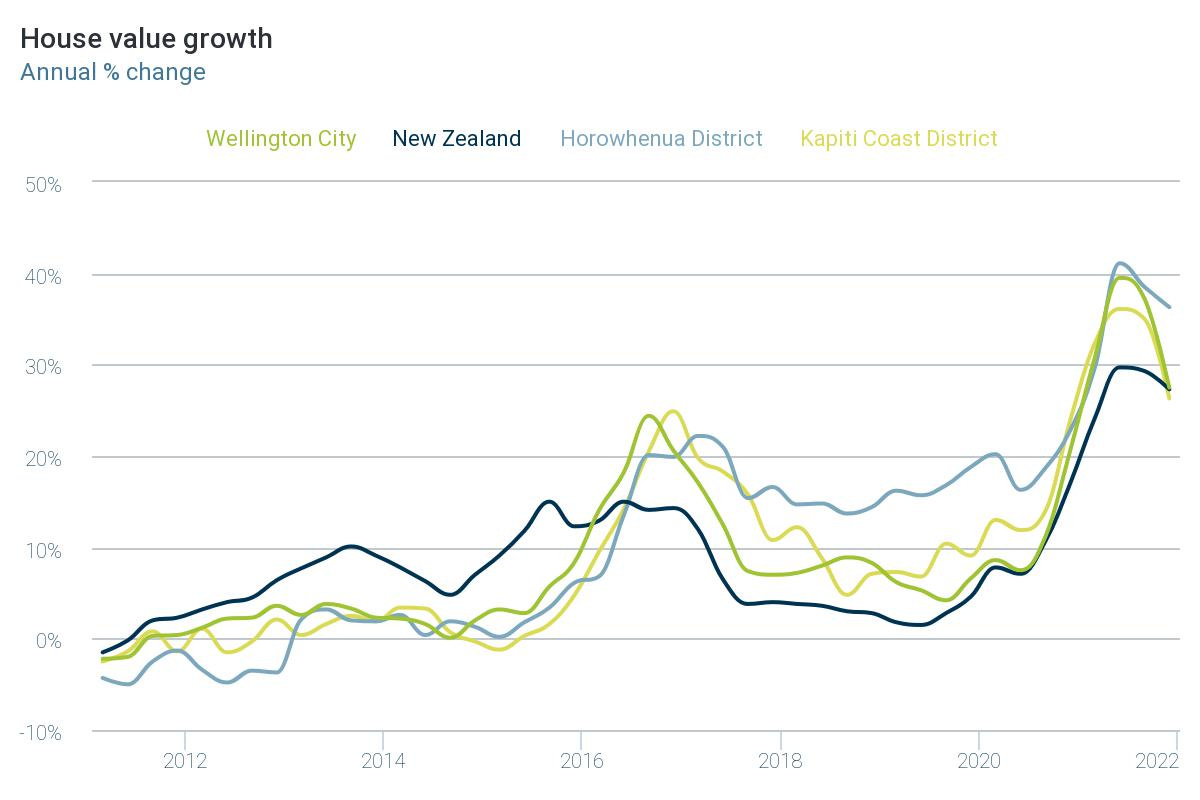

House and land prices have risen substantially more at the northern end of the motorway over the last five years than even in Wellington, which has been among the best-performing regions in New Zealand over the last five years. Construction started in earnest after 2017, especially once it was clear the new Labour government would honour the contract signed just before the 2014 election. This Infometrics chart shows how property owners at each end of the motorway have done versus the rest of the country.

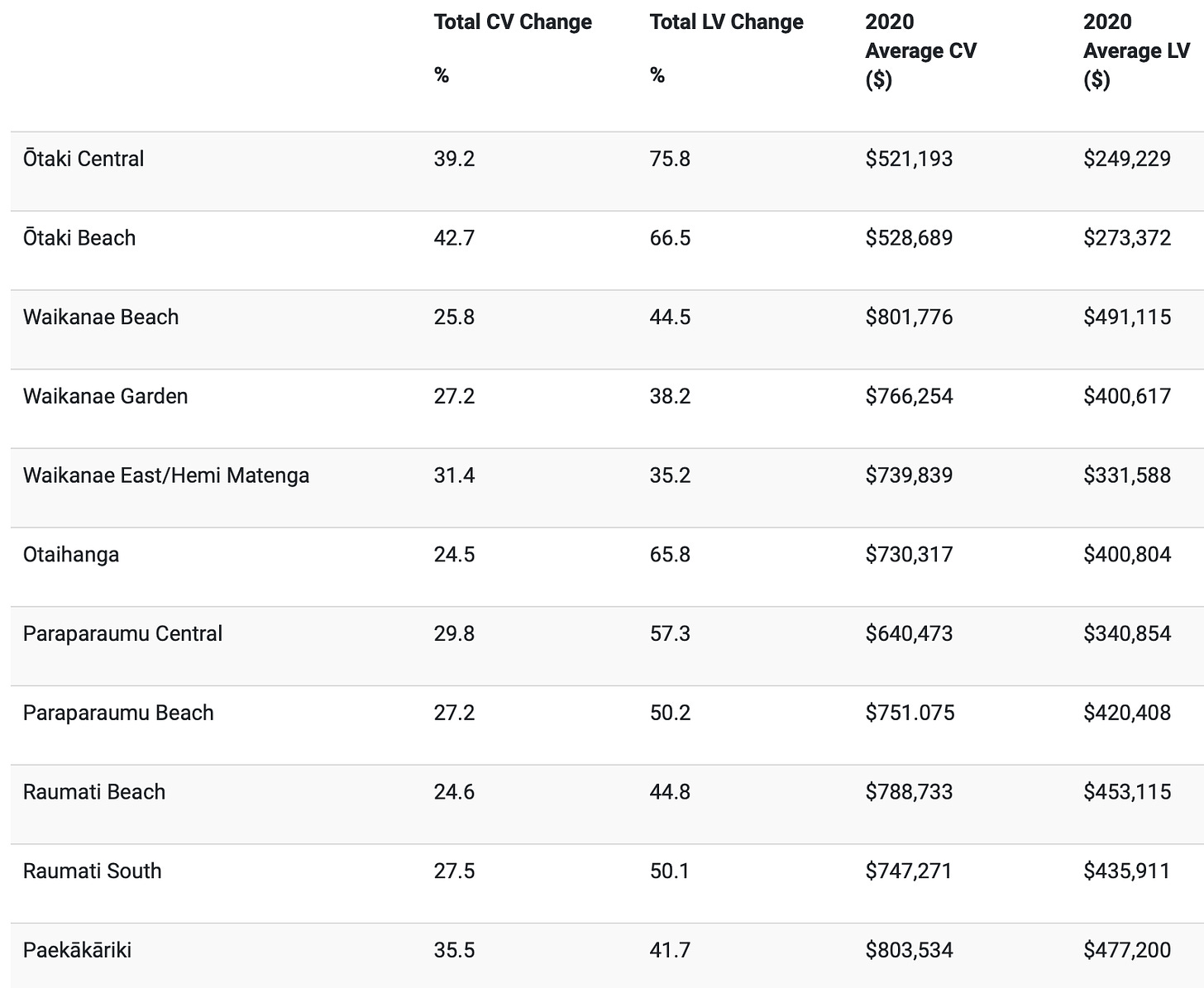

That’s evident in the latest ratings valuation changes noted by area in the Kāpiti Coast district. The LV refers to the land value change between council valuations over the three years to mid-2020, while the CV refers to the capital value change.

Tommy’s Real Estate sales director Nicki Cruickshank said in July last year there had been “terrific growth with the anticipation of Transmission Gully making the area almost more accessible to the city than many parts of the eastern suburbs in terms of time to get into the city”.

“The appeal of slightly better weather, the anticipation of the ease of travel and good public transport into the city have made the Kapiti Coast more appealing across all age groups whereas previously it was known for being more of a retirement destination.

“But now it is definitely harder for retirees to buy up the coast with competition from all age groups at the moment, in particular first home-buyers.

“A lot of young people are happy to make their lives up the coast, and because of the more affordable prices, compared to the city, we have seen large numbers of first-home buyers looking to establish themselves.”

A $1.25b road that made the land worth $2b more

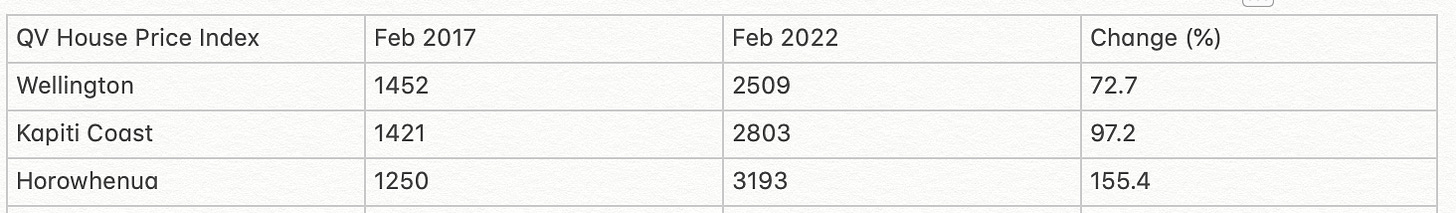

That time saving and the increased possibility of commuting saw prices double on the Kāpiti Coast over the last five years, while residential property prices rose 155% in the Horowhenua District. Both were faster than the 72.7% seen in Wellington City.

House and land values rose by a combined $10.3b for Kāpiti and Horowhenua to $30.6b in their last three-year ratings valuation cycles to 2020 and 2019 respectively (the black line in the QV chart below is the point of the last council ratings valuation for Kāpiti Coast). Their combined land values rose over those three year periods by $7.8b or 80.4% to $17.5b, consisting of rises of $5.4b for Kāpiti and $2.4b for Horowhenua.

If land values in these two districts had risen at the same rate as values for the rest of the country over the last three years, they would have risen by 51.4% or $5.8b. In effect, Transmission Gully was the major reason for the $2b out-performance of Kāpiti and Horowhenua land values over that period.

Why aren’t the beneficiaries paying?

These unearned capital gains over the last three to five years are of course yet to be taxed, and then only partially and lightly through the 10-year brightline tax on rental property owners. Owner occupiers and landlords who hold on for long enough won’t have to pay tax.

However, in other countries with capital gains taxes, at least some of those gains are captured. Many cities also use the capital gains more directly to pay for the projects through special land value-capture uplift rates. This tax would be imposed by a council on the landowner benefiting from the publicly funded infrastructure such as a road or railway to pay for that infrastructure. It is one of the ways the current government wants to pay for the Auckland light rail line.

National opposes the use of value-capture uplift rates and a capital gains tax, while Labour has ruled out a capital gains tax for the political lifetime of the current prime minister.

While many people were celebrating the long-delayed opening of Transmission Gully on Wednesday, few could have been happier than the homeowners who have already been benefiting from it for years.

Follow When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey’s essential weekly guide to the intersection of economics, politics and business on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.