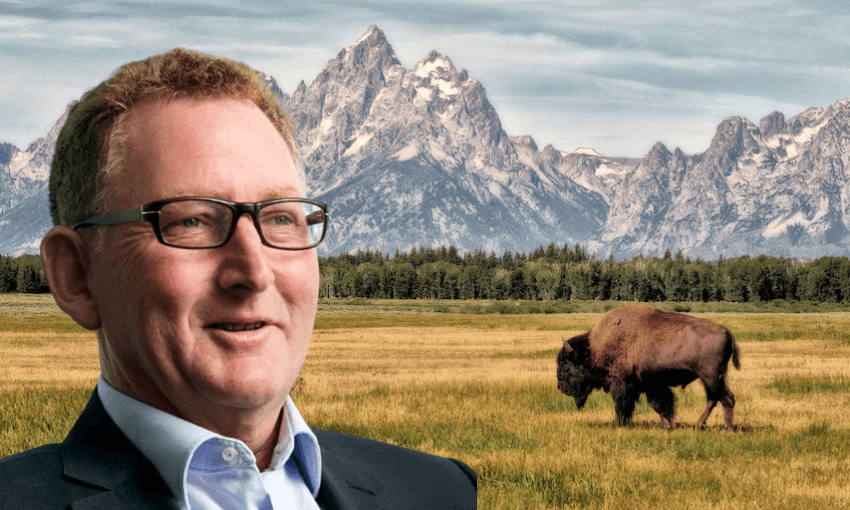

Just back from the famed economic conference, the Reserve Bank governor tells Bernard Hickey what he learned from his international counterparts, and what it could mean for New Zealand.

Reserve Bank governor Adrian Orr is just back from Jackson Hole, the US Federal Reserve-hosted shindig for central bankers, finance ministers and economists held annually at a resort in Wyoming. There, he says, the talk was of the increasing signs that disruptions caused by the Covid recovery and the war in Ukraine are pumping inflation into the global economy in a more permanent way than previously expected. And it’s a problem that central bankers are serious about getting on top of.

Orr told me about his impressions from Jackson Hole in an interview for the latest episode of my podcast When The Facts Change, which you can listen to below. Here are the key takeaways from our 30 minute conversation.

- Central banks are determined to establish their credibility as inflation fighters;

- Growth rates have been hit hard and in a more permanent way than previous thought;

- Most of Aotearoa-NZ’s inflation and interest rates are generated by global economic forces;

- Covid may have changed labour supply and practices in permanent ways that could improve productivity; and,

- Other central banks are interested in our Reserve Bank’s approach and its decisions to stop quantitative easing and start hiking interest rates earlier than others.

Follow Bernard Hickey’s When the Facts Change on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

‘Some of it’s longer-lasting and we’re serious about beating it back down’

The times they are a changin’ for everyone, and especially for central banks and the global economy. In 2020 and early 2021 they were seen as saviours of the global economy with their decisive interventions in the immediate wake of Covid, creating trillions of dollars to buy bonds and dramatically lower interest rates.

But as inflation surged towards double digit rates in much of the developed world this year, the view has shifted. Now central bankers are partly seen as the cause of inflation and their independence is being challenged because inflation rates are double and triple the targets they’re supposed to meet.

Nowhere was that more evident than at Jackson Hole, where hawkish talk about getting inflation under control rattled global financial markets and saw stock and bond prices fall 3-4%. This battle between central bankers and markets over the future of inflation has been focused on one place and one man for weeks. And it’s all because his view has changed so dramatically over the last year.

Near the end of August 2021, the world’s most important central banker, US Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell, was at Jackson Hole to tell attendees that the US Federal Reserve saw early signs of rising inflation in the wake of Covid as “transitory” and likely to “wash out” over time. He used the word “transitory” four times in a 2,800 word speech, which had the effect of reassuring investors worried that inflation might rise to dangerous levels.

Fast-forward a year and, back at the conference, Powell was in a much tougher and more aggressive mood, spending just 1,300 words to say inflation was now his main focus and he wouldn’t hesitate to act to squash it.

Among the 120 or so other central bankers and macroeconomists there to hear the speech, Orr noticed the transformation.

“Without doubt, the tone changed considerably. Jerome Powell set two records in his speech the other day, he came in under eight minutes for a monetary policy speech. So that must be amongst the world’s shortest,” Orr said.

“And he took around 3% off global equity markets, so that must be around one of the world’s most expensive speeches. They say small things are generally more expensive, and he delivered,” he said.

“He is reminding people that, first and foremost, [the Federal Reserve’s] primary concern is maintaining low and stable inflation. And yes, people have underestimated the scale and persistence of the shocks that the globe is going through at the moment… Once the economy shrinks, and its capacity to produce, once labor is scarce, capital is scarce, energy is more expensive, [then] the inflationary pressures are much higher and more persistent.”

Why we should care about the Jackson Hole talk

Orr made a point of explaining why the conference matters and how interconnected our economy, our financial markets and financial conditions are to the rest of the world.

“We are a very small economy bobbing around on a global financial ocean. And you know, the big swells and waves that come in that financial ocean are driven by the larger countries in the world,” he said.

“The US dollar is still the common denominator, largely in currencies around the world. So what is happening to US monetary policy, European monetary policy is still absolutely critical to what is happening to the New Zealand economy, and particularly around interest rates, exchange rates, and all things financial.

“The base level of interest rates are set internationally, not here. I would say the vast bulk, on average through time, for interest rates are determined overseas.”

‘A support group for central bankers’

Orr also reported back that central banks felt under enormous pressures.

“A little bit of that Jackson Hole gig was a victim support group for central bankers,” he said jokingly. “They are under immense pressure. Globally, it’s no different. And in each country, everyone’s got higher than targeted inflation. And everyone is wearing the blame for that, because our task is to keep low and stable inflation,” he said.

Orr said Covid and the war in Ukraine had effectively made the world poorer, which was putting pressure on central banks to demonstrate their value, and the importance of their independence.

“I think it’s important that central bankers always remain paranoid about losing their independence,” he said, pointing to the need for central banks to be transparent and explain what they can and can’t do.

“The perspective that I think people are missing is we have had a wealth shock. We are poorer as citizens of planet Earth, because of Covid, because of the climate change implications, because we keep going back to war,” he said.

“Monetary policy can smooth the pain through time, or shift it between sectors, but it can’t avoid pain.”

Climate change and a poorer Earth

Orr pointed out how climate change was also a factor slowing growth and introducing inflation, along with war.

“Earth is now poorer. We’ve got a sudden realisation around climate change, and so we’re seeing for any one investment, the returns are different or less. We’ve got much higher input costs, energy’s much higher, consumption costs and food. Whilst employment levels have remained where they are, hours of work are declining so we’ve got less supply capacity,” he said.

Orr said it was too early to tell how permanent lower growth would be.

“But without doubt, the signals are that long run growth is going to be on a lower trajectory, than say in the beginning of this century. So the lower trajectory is a partly around demographics, it’s partly around the shocks, the climate change shocks, and partly around the pandemic supply chains,” he said.

“Now, rather than ‘just in time’ stocking, it’s ‘just in case’ stocking. You are seeing quite a lot of general change in economic behavior that is not conducive to innovation or increasing higher growth. It’s constraining it at the moment.”

Good productivity news

Orr said there were some encouraging signs for inflation from worker productivity, and in particular working from home, which meant fewer hours to produce the same output.

“We’re doing that because we’re probably more productive. We’re probably now got more capital, our bedroom is now an office. It’s almost like a capital injection. And so that has heightened productivity, but it varies significantly across sectors,” he said.

“I would say you are in a new equilibrium where managers are going to have to be far more focused on managing outcomes, not inputs, having trust and confidence that you know that the people are there. And people are going to be far more flexible and demanding that flexibility in how they work.

“In the long run, over the next five to 10 years, I would say productivity and per capita growth will be back to a steady state level [to] what we saw pre-Covid. But we have to remember that level was a low-growth level, it was not a boom period.”

Follow Bernard Hickey’s When the Facts Change on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.