From extracting hemp oil to African artificial insemination programmes, a Christchurch-developed super refrigerator is taking the business of freezing to new levels.

An obscure piece of kit that began life in a government science lab is now on the verge of creating a new $100 million export industry for New Zealand.

Christchurch company Fabrum Solutions has turned a cryocooler developed by the old Industrial Research Limited (now Callaghan Innovation) into a commercial product that is solving a multitude of industrial problems.

Not to big-note it or anything, but NASA is using one of Fabrum’s cryocoolers to freeze carbon dioxide as part of the Mars Lander project.

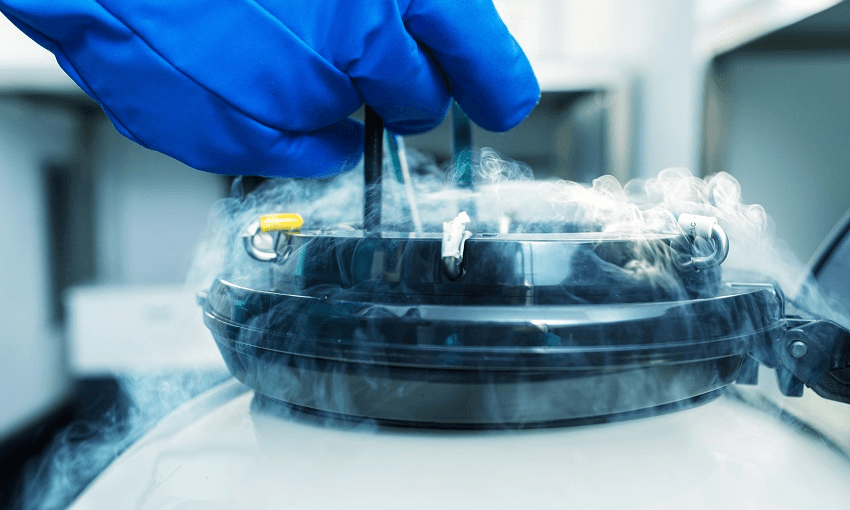

A cryocooler is a fancy refrigerator that operates at very low, or cryogenic, temperatures – from -170°C to -250°C.

Just to be clear, we’re not talking about cryonically freezing people in the hopes that they can be resurrected once medical science catches up. Uses for Fabrum’s cryocoolers are far less sci-fi, but are changing the game nonetheless. The key is that they can transform atmospheric gases such as nitrogen and oxygen into a liquid at the location where it’s required, and do it reliably.

“There are a whole range of uses we never appreciated when we started on this journey,” Fabrum co-founder Christopher Boyle says.

The engineering and manufacturing company is now receiving all sorts of colourful inquiries about its cryocoolers, such as from the hemp industry which is looking at using them in the process of creating biofuel. “They have to take large volumes of liquid and reduce the temperature, which doesn’t suit traditional freezer technology,” he says. Another use is in extracting hemp oil for vaping.

A significant market for Fabrum’s coolers will be in animal artificial insemination. Throughout Africa and other developing regions there is a push to lift herd qualities, but poor roading and infrastructure means transporting the liquid nitrogen required to preserve semen is a challenge. A Fabrum cryocooler can make liquid nitrogen on the spot, Boyle says. The coolers perform the same function in human fertility treatment.

While cryocoolers aren’t new, where the Kiwis have broken new ground is in reliability. Old-style cryocoolers were notoriously unpredictable. They work using a compressor and over time oil vapor from the moving parts would get into the working gas. This required regular servicing and the machine usually failed completely after a few years.

Industrial Research Limited (IRL), a former Crown Research Institute now part of Callaghan Innovation, developed a cryocooler with a compressor that is hermetically sealed. It means the bad stuff stays out of the working space and the cooler can keep running indefinitely.

Initially Fabrum thought its key market would be for cryocoolers producing on-site, on-demand liquid nitrogen, such as that used in artificial insemination. Then the Christchurch team received an unexpected call.

A US project was developing bioshelters for the American mining industry. The bioshelters are an underground haven in the event of an emergency and contain enough bottled air to keep miners alive for 30 days.

The only practical way to store that much air is in liquid form, with one litre of liquid air equating to 750 litres of the breathable version. Up until that point safely creating liquid air had been the preserve of scientific agencies such as NASA, but the Fabrum coolers paved the way for liquefying air on site. “We were approached because they needed a robust cryocooler. So along with (the US mine safety people) we developed the first liquid air plant,” Boyle says.

That development opened the way for myriad other uses. Anywhere on-demand liquid oxygen is required, from air ambulances to remote military bases, are now potential Fabrum customers.

Alan Caughley was the scientist behind the original IRL breakthrough. “Creating a mid-range refrigerator that produces a useful amount of liquid has been something of a holy grail,” he says. He likes to point out that scientist Sir Paul Callaghan – for whom Callaghan Innovation is named – said New Zealand’s strength lies in the “weird stuff” others don’t think to exploit. “Who on earth would have believed that in New Zealand we’re making a world-class cryogenic refrigerator?” Caughley says.

But inventing a cool piece of tech is one thing. Developing it for the commercial market is another.

Boyle and his business partner had been involved with the technology for a while and had done their market research. They formed a joint venture with French cryogenic engineering company Absolut System, and began working with Callaghan Innovation in 2014 to commercialise what was still a lab-based technology that sort of worked.

“In a period of three years we took it from a very green concept to a fully commercialised product,” Boyle says.

One of Fabrum’s customers is Robinson Research, the Victoria University-based superconductor research institute.

Superconductors are materials that conduct electricity at very low temperatures – hence the need for cryocoolers. They are used in technologies such as MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), and are gaining in mainstream use particularly in the power industry, deputy director Rod Badcock says.

The key difference with the Fabrum coolers is the reliability. Most existing cryocoolers are laboratory-type equipment and are not rugged enough for an industrial environment, he says. “We need the cryocooler to sit there and just run. We don’t want to be maintaining it on a weekly basis.”

Robinson Research is working with the Chinese Fuxing Hao high speed train network on developing high temperature superconducting transformers. “Longer term they’re looking at the potential for Fabrum cryocoolers to be the cooling system,” he says.

On Chris Boyle’s estimate that the market for Fabrum coolers is worth up to $100m a year, Badcock points out that Fuxing Hao wants to build 350 superconducting transformers. “Just on the transformers you could reach that,” he says.

Boyle says developing the cryocoolers has been a “four or five-legged Christchurch approach”, involving not only Caughley’s team which is based in the city but also Canterbury University and many local suppliers.

Leeann Waston, CEO of the Canterbury Employers’ Chamber of Commerce, says the tech sector is New Zealand’s third largest exporter, a fact which often gets overlooked, and Christchurch has a thriving and supportive innovation ecosystem.

People are now looking at the post-earthquakes city as a place of new opportunities. A number of tech companies are running pilots in the region, such as flying taxi operator Zephyr Airworks and electric vehicle ride sharing venture Yoogo Share, she says.

“It’s a great easy place to live, it’s affordable, you attract good staff, so all of those things make it quite a compelling proposition for businesses to either relocate here, or like Fabrum, to stay here.”