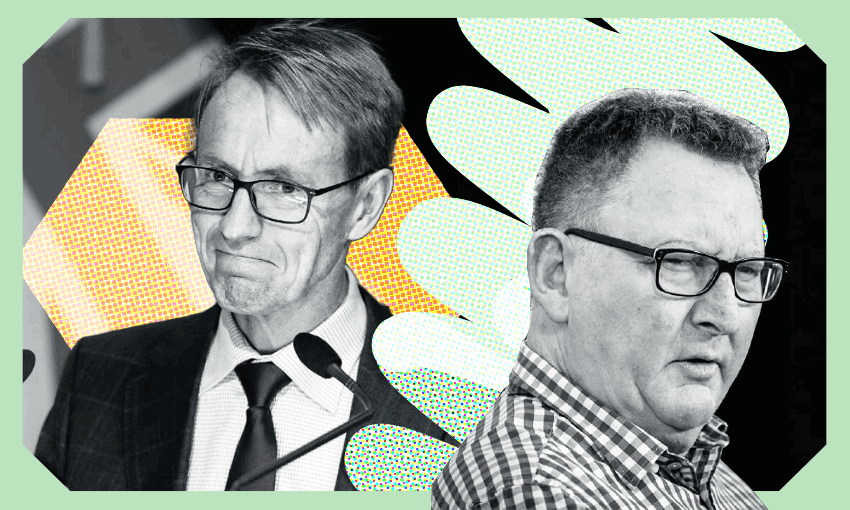

Adrian Orr is the new Ashley Bloomfield, whether you like it or not, says Duncan Greive.

On December 30, in one of the last set-piece news stories of the year, we learned Ashley Bloomfield was to be knighted. The former director general of health rose from anonymity to become an icon of the Covid-19 pandemic, surely the most unanimously popular public figure of that dark and fearful era. His unflappable demeanour and impressive recall of figures made him a platonic sex symbol and saw him lauded by slightly flustered New Zealand writers locally and on major mastheads around the world. His resignation and new title brings a satisfying conclusion to Ashleymania – but also leaves an opening for a new civil servant to draw hyper-scrutiny and quasi-fandom as we move into this new era.

Enter Adrian “cool the jets” Orr, governor of the Reserve Bank, the man whose simple and relaxing job it is to control the speed of our entire economy. His case to take Bloomfield’s mantle is unimpeachable. Like Bloomfield, he leads a bureaucracy which few think much about in ordinary times, but suddenly has a huge impact on our lives. His press conferences are guaranteed to lead the news, as he fronts decisions which have a decent chance at swinging election outcomes. Bloomfield was grounded by his unthreatening Baptist faith, Orr by his Irish-Cook Island background and working class origin story. Each carries a similarly formidable job title – governor and director general are each tinged with an earned combination of international intrigue and comic book simplicity.

Most obviously, just as Bloomfield taught us that we needed to prioritise health over the economy, Orr is now here to symbolically reassert the economy’s primacy over all other aspects of our life. Bloomfield became a pop culture figure, to a somewhat nauseating extent at the height of his popularity – fan fic, Etsy merch, cloying illustrations. So far Orr is a long way from developing a similar cult of personality. Data journalist Keith Ng’s good tweet bragging about still buying pastries despite Orr’s admonishments exemplifies a kind of simmering Daddy-culture waiting to develop, but it’s extremely nascent and uncertain to arrive at all. Still, it’s hard to deny that it’s Orr time now.

The Adrian Orr Show

If he never achieves Bloomfield’s fame, despite having Bloomfield’s impact, it’s likely to be due to chronic under-exposure. The Spinoff’s Anna Rawhiti-Connell memorably called the 1pm Covid-19 briefings “The Ashley Bloomfield Show”. These were a daily, extremely high-rating spectacle which featured Bloomfield using his knowledge and preternatural calm to talk us down from the worst of our fears.

The Adrian Orr Show, on the other hand, comes but seven times a year, in the form of scheduled Monetary Policy Statements and Monetary Policy Reviews. But even allowing for frequency, the vibe is off. The Ashley Bloomfield Show was like Shortland Street – a PG-rated spectacle for the masses, epidemiology we could all (mostly) understand. The Adrian Orr Show is more like a gritty HBO limited series – think the trading floor scenes from Industry, sadly without the drug-fueled sex.

The most recent Monetary Policy Statement was a classic of the type. Orr appeared in his banker’s suit, adroitly splitting the difference between the major parties through his royal blue-striped shirt and sombre maroon tie. He stood at the lectern to admonish us in grimly technical terms: “the productive capacity of the economy is constrained”, he said, because of our cursed inability to hold back “aggregate demand”. As a result there was little choice: “monetary conditions need to tighten further”. He wound up the terse opening statement with an ominous warning: “the committee remains resolute”.

Follow Bernard Hickey’s When the Facts Change on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

The overall tone is of a very exasperated head principal watching five million children refuse to come in from spending playtime and thus requiring a mass cash detention. Orr has none of the cutesy charisma of Bloomfield – but nor does he want it. He needs to be feared, not loved – all the better to achieve his ends.

The more we’re able to restrain ourselves, to Orr’s mind, the less fiscal pain he’ll have to inflict on us. Theoretically, if New Zealanders can just buy a few less pastries and robot vacuum cleaners, he won’t have to engineer a recession to get inflation under control. He has only a few tools at his disposal; the main one is the official cash rate, which dictates how much it costs to borrow money. He also has “forward guidance”, which is how much he says it will likely cost to borrow money in the future (which he can always change).

The last one is perhaps the most underrated: telling us off. That’s where “cool the jets” came along – it was Orr moving from the technical language of the central bank economist to the vernacular phrasing of a normal-seeming person. “Think about saving rather than spending – I know that’s a strange concept,” he joked (I think it was a joke). While some were mad about it, viewing it as deeply ironic that someone who fuelled the jets in the first place now demanded we cool them, it nonetheless achieved exactly what it was meant to, vaulting from the dry confines of a monetary policy press conference to the top of the 6pm news.

I want to defer to my colleague Rawhiti-Connell here for a spell. She not only wrote the first Ashley Bloomfield-as-pop-culture-figure piece, but also was first to theorise Orr as his replacement at The Spinoff’s recent Christmas party. I asked her to elaborate on her theory of the transition from Bloomfield to Orr, and she drew a line between their contrasting but compatible approach at the lectern.

“Orr’s press conference on November 23, contained traces of the direct, affable and confident style of communications that made Bloomfield so very good at the job of speaking to people, at a time when we needed someone to be very good at that. It’s not quite a ‘team of five million’ rallying cry, but he did, as Reserve Bank governor, stare down the barrel of the camera and suggest everyone could take on some level of responsibility for what most of us like to blame on ‘wider macro economic trends’, or just ‘the government’.

“Orr asked us to ‘just cool the jets’,” Rawhiti-Connell continued. “Specifically he said: ‘Think harder about your spending. Think about saving rather than consuming.’ On some levels, it was an absolutely outrageous thing for a Reserve Bank governor to do. There was a real risk that it could sound like moralising or overreach from a public servant whose job most of us assume involves invisibly and quietly twanging economic levers. It takes some guts to ask people, a month before Christmas, to stop spending. It was not necessarily appreciated – he was labelled a grinch, a Christmas-killer. But he landed a line very well. ‘Just cool the jets’ is a clever little bit. Like so many of the early Covid communications, it was simple, it worked well in headlines and it was an uncomplicated-sounding request for collective action.”

Most eras have had prominent civil servants occupying a disproportionate mindshare, from Susan Devoy’s vigour as likely the last Pākehā race relations commissioner to Christine Rankin’s weirdly swaggering time atop the MSD. For now, there are no other strong candidates for the role, and while Orr’s public profile does not yet match his predecessor’s, he is gaining. The pair are dead level on Google Trends over the past few months, and were it not for Bloomfield’s new year’s honour Orr would likely be ahead. But rest assured we’ll be thinking a lot more about Orr over the next 12 months. He’s just been reappointed for another five years (a move which initially infuriated the right, until they realised a recession would likely put a strong breeze into their election sails), and his pronouncements will be persistently analysed by everyone from investors to mortgage-holders.

We have to be aware that Orr and Bloomfield are very different personalities, built for different moments. Even when he was telling you to stay inside or you might die, something about Bloomfield made you warm to him. It feels grimly of a piece with the general trajectory of the world and stolen summer that he’s being replaced by a slightly dour economist threatening doom if you can’t keep your wallet in your pants. But that’s where we are in 2023, and perhaps what we need – Adrian Orr is in charge, and we have no choice but to pay attention.

The next episode of The Adrian Orr Show drops on February 22.