Over the weekend, New Zealand signed on to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership trade deal, also known as RCEP. What on earth is it, and what does it mean?

What’s the top line on this?

In the most basic terms, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP from here on out) is a trade agreement between the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Brunei, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines) and the six countries with which that group has a free-trade agreement. New Zealand is one of those countries, along with China, Japan, Australia and South Korea.

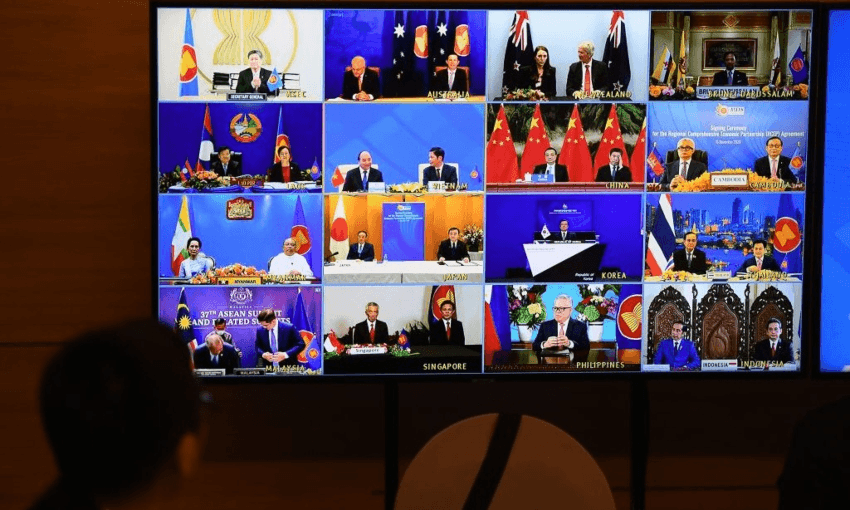

Technically, India also has a free-trade agreement with ASEAN, but after being part of the negotiations for many years, the country pulled out of RCEP. There’s a fast-track mechanism to allow it to come back in if it wants to. The whole thing was largely led by ASEAN, and negotiations have been thrashing around for most of a decade. It was formally signed over the weekend at a virtual summit.

Some of those are pretty big countries.

Overall, RCEP will cover about 30% of the world’s population, and cover about the same portion of global trade. As the foreign affairs and trade ministry (MFAT) summary put it,”the relative importance of the RCEP region continues to increase in the global context”. It probably shouldn’t escape anyone’s notice that many of the countries involved are those that have done a good job in getting Covid-19 under control, and are thus in a better position than many to accelerate economically out of it.

But not India? What’s that all about?

Securing a free-trade agreement with India was one of the major reasons New Zealand got involved in the first place. However, in the end Indian negotiators had some concerns that were too big to get around. A less important reason for them appears to have been the prospect of New Zealand dairy exports getting much more access. And a more important reason for India appears to be the current tensions with China – both in terms of being flooded with Chinese manufacturing exports, and some diplomatic and military skirmishes that have been taking place recently.

So what does New Zealand get out of RCEP, exactly?

Because New Zealand already has free-trade agreements with everyone else in the agreement, there’s not a lot in terms of market access for exporters. NZ International Business Forum executive director Stephen Jacobi said there have been some minor fixes to existing agreements, particularly with getting more goods into Indonesia, and some extra services trade in a few other countries, but they’re not wildly significant.

However, Jacobi said one advantage of RCEP is that it will consolidate trade rules into one place, which will make things a lot smoother for exporters. “And secondly, particularly in the trade facilitation space – the way goods move around – we have been able to make good gains. One is that all the RCEP members have agreed to a target period for clearance of goods through ports and customs, down to six hours. That is quite a big deal.” He added that there’s a new agreement on “non-tariff barriers”, and a speedier dispute settlement process around them.

We must be making a ton of money though?

Ah, no. Not really. MFAT estimates that the difference to New Zealand’s annual GDP will be between 0.3 and 0.6% higher as a result of RCEP going through, with it likely to be on the lower end of the scale, given India’s non-involvement. It’s not nothing, but it’s not exactly transformational either.

What about the wider message that trade deals send, in a diplomatic sense?

There’s a reason foreign affairs and trade are part of the same ministry in New Zealand – governments of both stripes have long held that they’re deeply interconnected in terms of the national interest. And for a small country, New Zealand is liable to be bullied without rules in place – trade minister Damian O’Connor said “it shores up support for international trade rules which small countries like New Zealand rely on, at a time when we’re seeing increasing protectionism”.

Jacobi put it even more simply, saying, “if we weren’t at the table, then these people would be making rules that we didn’t have a chance to have a say in. When we’re not at the table as a small country, we always lose. When China and Japan are negotiating arrangements, you can’t really rely on them to think of New Zealand.”

Who exactly is ‘us’ when it comes to major trade pacts?

Some would argue that New Zealand as a whole benefits from trade deals, so “us” means everyone. But one concern being raised by activists against RCEP is that the beneficiaries of trade deals aren’t necessarily representative of the country as a whole.

Edward Miller from the activist network It’s Our Future said “us” is whoever has the most effective lobbying capacity for the government. “So generally, our primary industry exporters and a few other major industries. Workers and unions, environmental or development organisations, digital privacy groups and others don’t enjoy the same kind of access and input throughout the negotiation process. For most of the country (and indeed most of the RCEP countries), trade and investment agreements are something that is done to them rather than by them.”

There were huge protests against the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. Why not with this?

Partly, it’s because some of the most controversial aspects of the TPPA (later renamed the CPTPP) weren’t included in this one. Professor Jane Kelsey, who staunchly opposed the TPPA, said those absences showed that citizens had become “wary and weary” of such deals. In particular, she noted that “there is no chapter on state-owned enterprises or government procurement, no right for foreign investors to enforce special rights through investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), some intellectual property rights for Big Pharma are absent or diluted, the electronic commerce chapter left out some rules and is not enforceable.”

When the TPPA protests were happening, the ISDS system and the prospect of Pharmac being weakened were two of the really big sticking points mentioned a lot by protesters. Also, this particular trade agreement wasn’t really heavily trumpeted by those pushing for it – they largely got on with it in secret, and the full text has only just been released.

Sorry, hang on, RCEP was negotiated in secret?

Yes. That’s not necessarily unusual for trade agreements, or any sort of negotiation really – secrecy about what gets said in the room allows those doing the negotiation to speak more freely, and trust the process more. But for many opponents, there’s something quite sinister about powerful people sitting in (possibly) smoke-filled backrooms, making decisions on behalf of millions of people. The current government has sought to counter this impression through a feedback and consultation process run over recent years, called Trade For All.

What about Māori interests, and the Treaty of Waitangi?

There are two points to make here, said Chris Karamea Insley, the chair of Te Taumata, an entity that champions the views of Māori in trade negotiations. The first is that Māori businesses are generally over-represented in the primary industries, and so the ability to export is crucial. “We know that one in every four jobs that gets created in New Zealand is directly derived from international trade. Jobs are so fundamentally important to our Māori people. We need trade enabled for products from our farms and our businesses, in order to be able to employ our people at home.”

And the other important point is that RCEP enshrines the pre-eminence of the Treaty of Waitangi within New Zealand. Karamea Insley said that in recent years, this has become normal for New Zealand’s negotiating position – but that wasn’t the case in the past. And other countries are now aware that “it’s not negotiable that it’s not included” for New Zealand.

So RCEP is now in force, whether we like it or not?

Not yet. The full agreement will take several years to actually implement. And in the world of international trade agreements, that’s not really slow, given it took eight years to get over the line in the first place.