After several major NZ companies pulled their ad spend from Magic Talk, Ben Fahy assesses an increasingly activist corporate communication posture, and how deep the commitment runs.

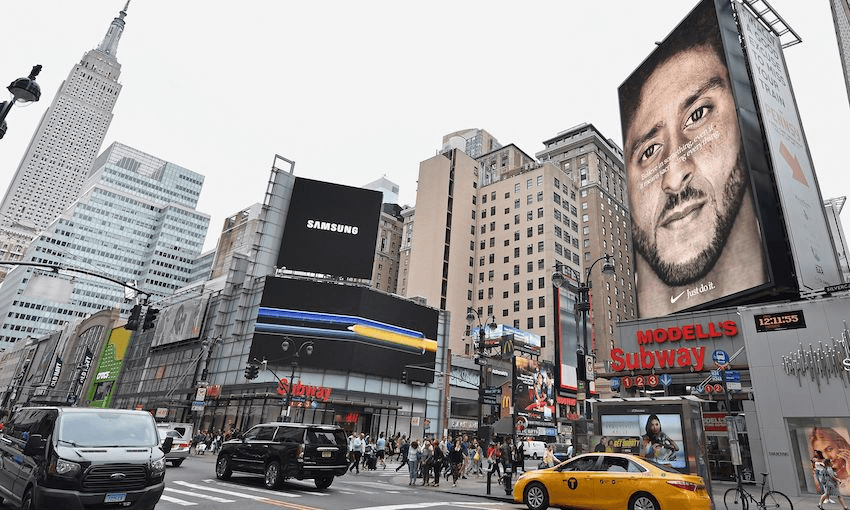

Back in 2018, Nike launched a campaign featuring NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, whose protest against police brutality directed at the Black community saw him take a knee during the national anthem. Many praised the company for backing him and a range of other athletes who “dreamed crazy”, while others burned their own Nikes in protest and questioned the wisdom of alienating customers who didn’t feel the same way.

Perhaps not surprisingly given the levels of polarisation in the US at the time, it was a very divisive campaign, but, as founder Phil Knight told Fast Company: “It doesn’t matter how many people hate your brand as long as enough people love it. And as long as you have that attitude, you can’t be afraid of offending people. You can’t try and go down the middle of the road.”

The middle of the road has traditionally been a very popular route for risk-averse marketers who often seem more interested in job preservation than rapid growth or pushing social progress. But, as the Nike campaign suggested, brands that claim to believe in something seem much more willing to sacrifice everything – or at least deal with the consequences of taking a stand. So are these companies legitimately concerned about these issues, or are they simply doing what companies do best and following the money?

Last year, a range of big brands boycotted Facebook because of growing frustrations around the platform’s attitude to hate speech and dis- and misinformation. This week, Facebook’s decision to pull news from its platform in Australia has sent shockwaves around the world – and led to major ad agency Phd questioning its safety as a place for its clients to communicate. And more recently, Vodafone, Kiwibank, Trade Me and Spark pulled their ad spend from MediaWorks-owned Magic Talk after racist comments from a caller were endorsed (and enhanced) by fill-in host John Banks.

Where companies choose to advertise is usually based on where they think their potential customers will be, but advertising is an implied endorsement and, as Dolly Parton so wisely sang: “I think you’re an angel / But folks think that you’re cheap / Cause you’re known by the company you keep”.

The pulling of ad dollars is often a temporary response to the blowtorch of public scorn; an attempt to limit the negative impact on typically well-curated brand associations. For some, the woke alarm goes off when they hear about decisions like this, but money – and particularly the threat of losing it – is a great lubricant for change. Larry Fink, the CEO of one of the world’s biggest fund managers, Blackrock, said in his 2021 letter to shareholders that “climate risk is investment risk” and “companies that are not quickly preparing themselves will see their businesses and valuations suffer”.

In marketing, reputational risk is also investment risk and, just as in politics, perception is everything. This means brands regularly conduct research to ensure they’re creating the right perceptions among customers and non-customers. They also study emerging cultural trends, attitude shifts and evolving media habits so they don’t end up on the wrong side of history.

Whether it’s through the use of colours, jingles, logos, fonts, tone, ads, slogans, sponsorships of teams, events or TV shows, or, increasingly, backing social and environmental causes, you can see why companies go to so much trouble to ensure they’re perceived positively when brand value is estimated to contribute an average of 19.5% of enterprise value. As business professor and podcast host Scott Galloway jokes, brand is Latin for “irrational margin”: “From the end of WWII until the introduction of Google, the gangster algorithm for shareholder value was simple – create a mediocre, mass-produced product and infuse it with intangible associations. You then reinforce those associations through cheap broadcast media, which occupied the average American for five hours a day.”

There are no mind control tricks at play here, however. There’s just a correlation between likability and likelihood to purchase, which is why the ad industry regularly promotes research that shows creativity can be a revenue generator. If you don’t like bananas and then you see a great ad for bananas or notice a banana company supporting gorilla rehabilitation, it probably won’t change your mind. But if you do like bananas, there’s a better chance you’ll choose one brand over another similar brand and potentially pay more for it if you like it. And it’s not just because those bananas are objectively better (even if they are): that more likeable brand might just make you feel a certain way or project a certain image.

While the conventional wisdom is that brands need to be consistent, they really just need to be relevant and embed themselves into the cultural context. Toyota, Ford and Hyundai, despite being Japanese, American and Korean companies respectively, have spent millions attempting to become more New Zealand-y over the years, and they’ve done it very successfully. In an interview with StopPress, ex-FCB strategist David Thomason talks about how Coca-Cola, a sweet, delicious fizzy drink with little to no nutritional value, connected itself to World War II, the Vietnam War and race relations. It wasn’t always overt, but its ads acknowledged the issues of the time and the brand went on to become a symbol of freedom and democracy (Pepsi, however, failed dismally in its attempts to be relevant in one of the most pilloried ads in history, so it’s a fine line).

Patagonia, a brand that was started by climbers and is now worn by teenagers because it’s cool, acknowledged environmental tension in its ads by famously telling people not to buy one of its jackets on Black Friday. Allbirds has done it too, by putting the carbon footprint of all its products on display and hoping the powerful force that is peer pressure will see its competitors follow suit.

Media and advertising tend to reflect culture, but they can sometimes create it. One of the most successful examples of sophisticated/manipulative social engineering is the diamond industry’s efforts to convince people that paying a huge amount of money for a reasonably common mineral was the best way to show your love for someone. This orchestrated campaign was purely for the benefit of the advertiser’s bottom line, but that cultural influence can also be used to push society in certain directions. These days, it’s not uncommon to see companies endorsing certain lifestyles, featuring marginalised groups, or attempting to quash taboos in their ads. Giving something tacit approval by showing or mentioning it publicly can help speed up acceptance and, in some cases, these brands’ policies are ahead of regulation because it’s something they believe in – and, just like publicly backing a movement or deciding not to support an unethical media channel, something they believe will eventually have commercial benefits.

Most large companies already have fairly comprehensive brand and advertising guidelines. So how does a company decide whether media is ethical or not? How far will companies go when it comes to switching off big, bad media channels? And could a new breed of marketing managers and culturally aware exec teams or CEOs force media outlets to start appealing to our better angels by threatening to pull ad spend?

Ads tend to follow eyeballs and many big brands still crave that next hit of sweet, sweet audience, as the Super Bowl and the 6pm news continue to show (despite its lack of concern for the truth, Fox News also just reported a 14% increase in ad spend in 2020, so for every advertiser pulling out of something on principle, there are many more willing to place ads purely to reach potential customers). A whole range of advertisers, including some of those that were involved in the boycott, are also still supporting Facebook (or one of its subsidiaries), even though it’s played a role in splintering society, doesn’t pay enough tax and regularly showcases a range of human terribleness. Many are also happy to run ads on YouTube even though, well, ditto. Pressure from advertisers and activists has led to some improvements on those platforms but, as journalist Kara Swisher says, social media’s business model is still largely based around enragement and engagement.

Vodafone’s updated advertising policy acknowledged that it wouldn’t always get it right (and that it wouldn’t use its ad spend power to pressure media into running favourable editorial). But companies are entitled to change their attitude when they receive new information. Most of us have experienced this ourselves: when good old Uncle Bob tells you Bill Gates is implanting tracking devices into our bodies through vaccines, when your best friend tells you he killed a man (don’t worry Tim, I’ll never tell), or when your favourite actors, artists or sportspeople have their chequered pasts revealed, it can change our relationship to those people and to their creations – and it’s next to impossible to un-know something once we’ve discovered it.

Cynics might suggest that brands aligning themselves with progressive ideas is the equivalent of paying for a few trees to assuage your crushing environmental guilt after a plane ride; “purposewashing” that aims to divert attention away from some bad behaviour or egregious profiteering. Humans despise hypocrites (and also, unfairly, Hippocrates) so expressing solidarity with a cause and not living up to it in real life, as some brands that made public statements following George Floyd’s death found, is the branding equivalent of the family values campaigner getting caught in the bondage club. The media (and the social media mob) will undoubtedly be on guard to keep those who publicly walk the path of purpose honest and hammer those valuable brand associations when they’re not. After all, character is what you do when no one is watching, while ads and statements are what you make when everyone is.

And in case you’re wondering, after a bit of a dip in Nike’s stock price when the Kaepernick campaign launched, purpose eventually led to profits and it hit at an all-time high this January.