Our box-fresh prime minister sat down Auckland’s CEO set for his first public audience yesterday. Duncan Greive was there.

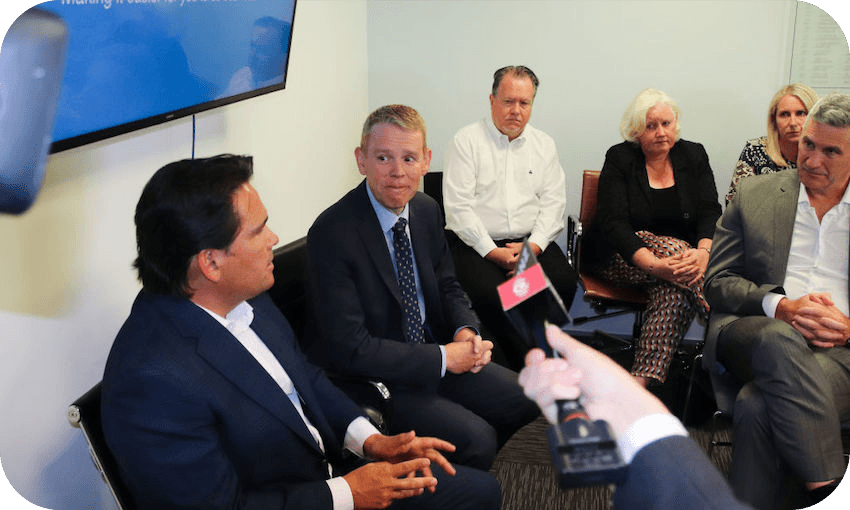

“I did say we wanted to get closer to business,” quipped our very new prime minister, Chris Hipkins. He sat alongside former National leader, now Auckland Business Chamber CE Simon Bridges, and stared down an audience of 40 or so leaders of the country’s biggest businesses. Hipkins was referring to the way the Chamber’s boardroom was crammed knee-to-knee with CEOs on office chairs, not a table in sight, all eager to make his acquaintance and share their views on exactly what he needs to do to win back, if not their love, then at least their grudging acceptance.

Earlier that morning a package on RNZ’s Morning Report had made it clear just how poisoned the relationship between small business and the government had become. They called a dairy owner – he was mad. They called a caterer – she wasn’t happy. They called a man who owned a provincial airline – he was displeased. They called a farmer – he was downright furious.

Labour doesn’t exist to make friends with the business community (there’s a clue in the name). But neither does it want to cultivate the kind of brazen hostility which characterises the current perspective of many in the private sector. It wasn’t always this way. Grant Robertson has often spoken to business audiences, establishing a level of real respect, while Jacinda Ardern established the Prime Minister’s Business Advisory Council to solidify a formal channel for the communication of their views. It’s perhaps telling that its founding chair was Christopher Luxon, then the boss of Air NZ, now leader of the opposition.

The project worked for a while, but has decayed markedly over the past couple of years. It’s easy to miss just how septic the relationship has gotten, and Hipkins nodded at this with remarks acknowledging the length of the Auckland lockdowns, a festering source of discontent which can sometimes feel forgotten by senior politicians and the press gallery. But it goes beyond the immediate realities of the pandemic response, and more into its profound echo.

The group of businesses canvassed by RNZ neatly encapsulates why. The dairy owner has stopped the very profitable sale of cigarettes to deter thieves. The caterer has found immigration settings so tight she can’t hire a chef. The farmer saw climate change regulations as penalising him while many other countries have yet to price farming emissions. All have absorbed an extra public holiday and five more sick days, which if fully utilised would reduce work days by more than 2%. Elsewhere, fair pay agreements, unemployment insurance and a more inquisitive Commerce Commission.

Above it all, the highest inflation in decades, stubbornly refusing to be tamed, with concomitant pressure on wages. For some businesses this is almost something to be shrugged at – New Zealanders have no choice but to use petrol retailers and supermarkets, which can simply pass on their increased costs. For many other businesses there is no such facility, and they are understandably freaking out over margins squeezed to the red. Mediaworks’ CEO Cam Wallace wasn’t in the room, but that’s what has driven his announcement that 90 jobs are to be cut from the radio and outdoor advertising giant.

Many voters, particularly Labour’s natural supporters, will have little sympathy for the plight of the CEO, especially given that Covid brought supernormal profits to some businesses. But Hipkins knows that publicly grumpy bosses of major businesses might well be enough to sink his already difficult path to re-election. He spoke of their shared interest in creating good jobs, and made a commitment to “getting rid of any impediments to that”. The room looked sceptical, and before long the doors were closed to allow for a “free and frank conversation”.

What was discussed will remain known only to those who stayed in the room. The whole event felt intentionally symbolic. After five years under Ardern in which the stated focus was on child poverty, on improving relations with Māori, on reforming systems which have failed the most vulnerable, Hipkins’ decision to make his first public appearance as prime minister with an audience of older, grouchier business people powerfully signalled his intentions.

This should not be read as an abandonment of Labour’s core constituencies, more an acknowledgement that without repairing this frayed relationship, there might be no plausible path to power. It remains quite difficult to achieve your policy goals from opposition. It’s unlikely that an hour in a crowded room of suits will be enough to win over the country’s big employers, but the group will appreciate having its role in society acknowledged with this conspicuous place on Hipkins’ schedule. It’s yet more evidence that despite his strong ties to the old regime, this prime minister intends to try and convince the electorate that it doesn’t need a change of government, because it has already had one.

Follow our politics podcast Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.