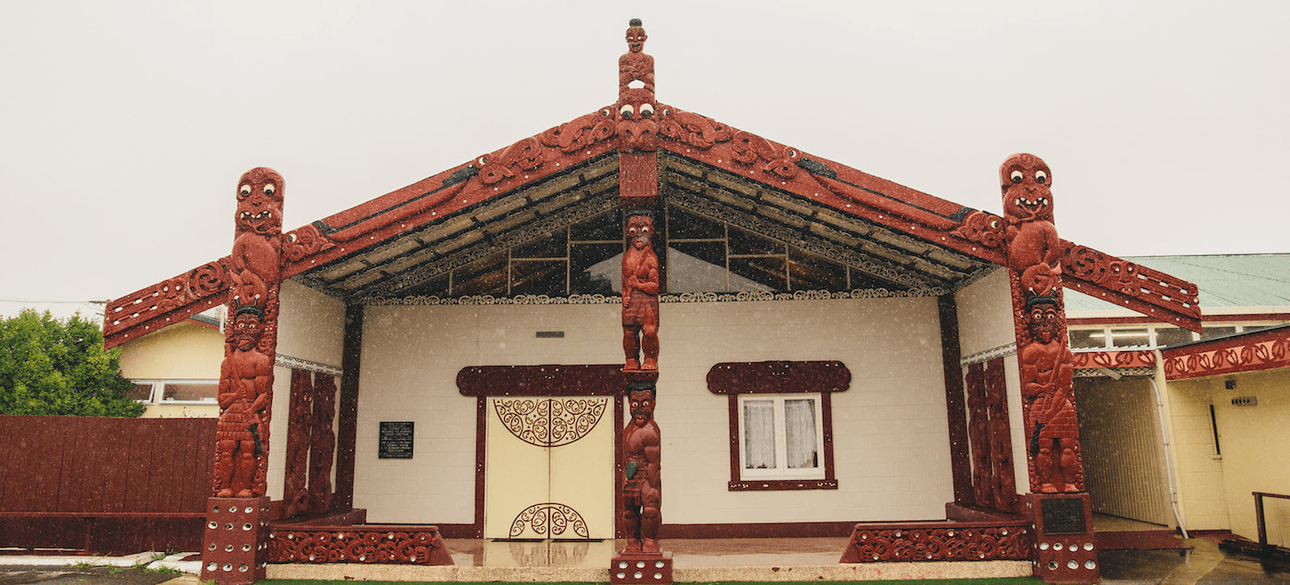

Te Puea Memorial Marae has become the epicentre and symbol of Auckland’s homeless families. The Spinoff’s Madeleine Chapman spent a week volunteering there to compile this report. Photography by Qiane Matata-Sipu.

The Warehouse has agreed to match all donations delivered through this story – scroll to the bottom for information on how you can help.

Two teenage boys wearing school uniforms walk out through the marae’s back gate. They’re passing a rugby ball between them and cracking jokes at each other’s expense. A woman walks by with shopping bags and they help her carry the groceries back inside before resuming their game. They look tidy, happy, normal. And if we were anywhere else but Te Puea Marae, I wouldn’t have given them a second glance. As they head down the driveway and off to school I wonder if their classmates and teachers know where they’ve just come from every morning.

When I first heard that Te Puea marae was providing food and shelter for the homeless, I imagined rows of mattresses on the floor and hot coffee in styrofoam cups. That’s my memory of marae sleepovers in primary school.

Instead, when I arrive on Monday to drop off some food, I’m stopped by a warden in the middle of the road. Once it’s clear I’m simply dropping off a donation, I’m directed to a makeshift front office where Crystal, the wardens team leader, greets me. She thanks me more than once for my very modest offering and asks that I sign the koha log book. There are pages and pages already filled with donations from the past month. I ask her if they are still needing volunteers.

“Oh yes,” she says quickly, “we always need volunteers.”

Is there a particular day that is usually short on help? I had planned to volunteer and, like a true philanthropist, wanted to cram all my charity into half a day. Crystal thinks for a moment.

“Probably weekdays, because people have work and stuff.” There is a pause before she adds, “actually Sundays are usually pretty quiet too.”

I don’t say anything and wait for her to complete the week by saying that in fact, Saturdays are the quietest days of all. Instead she concludes cheerily “just any day you can help is awesome!”

Despite the outpouring of support from New Zealanders in the form of food, clothing, toiletries, and koha, Te Puea still finds itself lacking in volunteers to help with the daily running of the marae. What started as a simple call on Facebook asking what the marae could do for those whānau sleeping in cars has turned into an extraordinary accidental Kickstarter for social services, with 93 (as of this week) people passing through Te Puea and being placed in either temporary or permanent accommodation.

*

When I arrive the next day at 9am there is a small group of people waiting to be given their initiation. I join two friends who are also volunteering for the first time (“we’re on holidays and my Mum told me about this place”) and we are shown around the grounds. I’m assigned to work with Taehuri, who monitors all food and clothing going in and out of the grounds as operations team leader.

From what I can see, no one actually sleeps inside the marae. The majority of residents are in rent-a-room containers, the kind you see at construction sites being used as temporary offices.

I get assigned to can duty, meaning sorting and labelling the donated canned food that sits in the corner of the clothing room. I’ve never seen so many cans in my life. There are pillars of boxes filled to the brim. Baked beans, spaghetti, fruit, soup, fish and vegetables. A lifetime supply of cans, not to mention the mountains of rice, pasta, and other foods in the next room. Before I can help myself I’m wondering whether there might somehow be too much. Surely they don’t need this much food.

But just as quickly I remember going grocery shopping as a child with my mum and how we used to fill up two trolleys every week. “It takes a lot of food to feed ten kids,” my mum would say. I look around at the rent-a-rooms and the communal kitchen, the cardboard boxes waiting to be used for food packages. There are a lot more than ten kids to feed.

“The first thing they come for is a cup of tea. If they’re hungry, we feed them. Want a shower? We chuck some towels at them and they grab a shower. If they need clothes we find them clothes. After that we have an assessment to see what it is they need most and first. We have WINZ there to make sure that these people are getting everything that they’re entitled to.”

That’s Johnboi, resources team leader, speaking to a visitor as he gives them a tour. It seems simple because it is simple; people come to the marae in need and the marae tends to those needs as efficiently and best they can.

Some days are easier than others. It’s raining outside and will continue to rain all week. Johnboi knows that rain makes for more work.

“At the end of the day we always have donations coming,” he says. “The rain doesn’t keep those away but the volunteers it does. We have about 16 of our family members on site who have dedicated their time to our kaupapa – but we always need more hands.”

Every once in a while I am snapped at by someone in charge in a way that reminds me of getting told off by my Samoan aunties at family reunions. There is an inherent understanding that everyone is there for the same reason and so polite niceties are not a top priority. At the same time, it is made clear on numerous occasions that my help is appreciated and I’m free to leave whenever I feel I’ve had enough.

After a few hours, a hot lunch is provided to all the volunteers. We sit at trestle tables in the dining hall. A number of today’s volunteers are new, like myself. We are all still marvelling at how much Te Puea is able to achieve in half a day.

“If this is what you guys are doing, what is the government doing?” It’s the question on everyone’s lips, having just been voiced by a new volunteer, and one that has yet to be answered. The older women just shrug and continue eating what is actually one of the tastier lunches I’ve had in some time.

This is not bad, I think to myself as I look around at the pork stew and freshly baked biscuits waiting to be taken out to the residents’ eating area. This is not bad at all. But 20 minutes later I’m on the bus heading home to my own bed in my own room. Because despite the small home comforts – the clothes, the showers, the baking, the fact that they’re called “residents” – these families are still without a home.

On the second day I see no volunteers from the day before and Taehuri is pleasantly surprised to see I’ve come back. Suddenly I’m in charge of showing new volunteers the ropes. Besides the full-time staff, it’s rare for people to volunteer on consecutive days. While I’m stacking bags of flour I hear people talking about a visitor walking outside.

“Who’s that Pākehā man? Is that John Keys?”

“I doubt it.”

It’s not John Keys. It’s Labour MP Phil Twyford, looking very out of place in a business suit and white skin. He and his briefcase are being given a tour of the marae. They pass through the food store room where I’m sorting and labelling.

“You’ve got a lot of food in here,” he says in a tone that sounds familiar. Whether or not he remembers going grocery shopping as a child remains to be seen. A few moments later I hear him filming a segment for his Facebook page out in the clothing room.

When a volunteer arrives at Te Puea, they are assigned to one of three areas: Kitchen, Food, Clothing. Except no volunteer gets placed in the clothing department because there’s a small group of Māori women who run the show and have been there from day one. Nobody messes with the clothing department.

When Phil leaves, I hear the clothing team having a talk next door. There had been a heated exchange earlier and one of them had gotten upset.

“We’re a family,” I hear someone say, “if you’re family and you want a break, take a break. Make the most of the volunteers who have given up their time to be here because there’s no use in us burning out.”

No wonder everyone seemed a bit short with me yesterday. The leadership team can’t put a lot of effort into making volunteers feel like they’re changing the world. They have far too much shit to do to be spending time stroking egos. Most of the time there aren’t enough hands to complete all the tasks but every once in awhile a group of volunteers will show up at once and suddenly there are too many bodies in the tiny rooms. Taehuri has had to turn away volunteers before (most recently a group of young offenders on probation) and laments a wasted opportunity.

“I hated turning away those volunteers but sometimes when a whole bunch come at once, it’s just too much,” she says. “It breaks my heart because these people’s spirit and soul bring them here and I just can’t organise them all at once.”

On Thursday morning I arrive at Te Puea to the news that I have been promoted. “Do me a favour please and be in charge here for a little bit.” Taehuri is hurriedly sorting out odd food donations in the office. “I’ve got a meeting in the marae. I’ll be back in half an hour.”

I sit down at the desk and try to look busy. Just as Taehuri returns, a young man drops off some baking and we take it down to the residents’ kitchen. A young woman is eating breakfast when we enter and she exclaims about the new treats.

“Did you try that brownie that someone dropped off yesterday?” she asks Taehuri excitedly, “It was double chocolate oh man it was good! There’s still some left for you.” Taehuri laughs and promises that she’ll try it after lunch.

Throughout the week I have heard volunteers talk in a way that suggests they live on the marae too. I start to wonder if perhaps they are actually residents and are helping out while waiting for a home but soon learn that for some of them, like Johnboi, who’s lived there for almost nine years, the marae is their home. They are not simply inviting whānau into their community, but literally into their home.

“It’s opening our home, and so we should,” he says. “We never lock our doors on our marae. People come in to the whare tupuna [ancestral house] who just need guidance, maybe just need a cry too. We’ve seen some people like that.”

On Friday, my last day, a lot of the senior volunteers are absent. They’ve gone to Wellington for the weekend to perform kapa haka at Te Papa for the Matariki festival. I’m a little sceptical about how things will go while they are gone but everything runs as smoothly as ever. Of course, there is a lot of bickering.

These people aren’t trained in social services. It is not their job to house the homeless and organise for government agencies to help. But they do it anyway, and Johnboi hopes that soon someone else will step up.

“We’re just here to support during winter and we’re hoping that the agencies, the government, have opened their eyes by then.”

Back in the cans section I’m once again treated to the gossip and good music of the clothing department. All week they have been nothing but gracious, humourous, and hardworking. They swear occasionally but ultimately speak as you would imagine your dear aunties to speak. Then somebody mentions that a woman had come in to the room yesterday and tried to take over.

“She just tried to act like she was in charge.”

“I was like ‘no’.”

“Then she wanted to check our bags to see if we’d taken anything.”

There is an outburst of shock and disgust at the assumption that they, volunteers who have worked overtime to sort and bag mountains of donated clothing, would try to steal some of it. Why would she think that? The answer comes in a calm, quiet voice from one of the aunties.

“Because she’s a cunt.”

I try not to laugh too loud in my can corner as the rest of the women murmur their agreements.

Unbeknownst to me, something better than an aunty calling some woman a cunt is about to happen. Today is the day that B and her family are leaving the marae. B, her dad, and her four siblings have been at Te Puea for 12 days. B’s cousin drowned at Hunua falls in March and soon after she was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Her family moved to Auckland from Hamilton so that she could undergo treatment at Starship Hospital. After staying with nine others at their aunty’s house, B’s family had to leave and had nowhere else to go, so they went to Te Puea.

After B’s story gained traction online, a state home was soon found for them to live in.

Everyone is ordered to stop whatever they’re doing and head into the marae to farewell the family.

It’s a small ceremony with a few media outlets filming. B and her two younger brothers are seated at the front while a welcome prayer is said.

The whole affair is very short. I was expecting a long meeting with multiple speakers and songs. Instead there’s a short intro and marae chairman, Hurimoana Dennis, speaks briefly about how it’s bittersweet to say goodbye to a Te Puea family.

“We’ll never forget you… it has been our privilege and honour to help you get on with your lives. That’s all these people want. They just want to get on with their lives.”

In less than half an hour, it’s over. A huge moment for B, her family, and the marae. Many tears are shed as each and every volunteer embraces B and wishes her luck in the future. Promises are made to keep in touch and to keep fighting. The marae has done its job and helped a homeless family find a home. Through the help of the public’s donations, the volunteer hours, and yes, the government agencies, a family in desperate need has been given a fresh start.

But now everyone has to get back to work. There are more families without homes. So Te Puea’s work goes on.

A version of this story will appear in a forthcoming issue of Mana magazine.

How you can help:

Donations – There are a few specific items that Te Puea are always in need of so The Spinoff has teamed up with the fine folks at The Warehouse to help make this happen. Click on the image below – or here – to purchase any of these items and not only will The Warehouse match your purchase with an equal donation of their own, they’ll deliver to the marae for free. Legends.

Volunteers – Volunteering is the cheapest and most direct way to help and here’s the great thing, it’s pretty easy to do. Te Puea marae is extremely close to a number of bus routes, especially if you live in and around the city.

304, 305, 327, 328, 348, and 354 buses all leave fairly regularly from Britomart or Midtown and travel through UoA, Newmarket, and Epsom. Hop off at the first stop after the Southwestern motorway bridge and it’s a five minute walk to the marae. Easy as!

To donate directly to Te Puea’s Givealittle page, click here.

Te Puea Memorial Marae

41 Miro Rd

Mangere Bridge

Auckland 2022