The greatness of The Last of Us Part II lies not in the gameplay, but for the conversations it will start, writes Sam Brooks.

Major spoilers for The Last of Us follow, but no spoilers for The Last of Us Part II.

In the seven years since the release of The Last of Us, the landscape of video games has changed hugely. We’ve lived through one Gamergate, the rise of streaming, the dominance of battle royale shooters, and the release of Final Fantasy 7 Remake. Conversations about gaming that were once on the fringes, conversations about representation and accessibility, are now nearly unavoidable if you’re paying attention. But we’re at the end of another era now. Just as The Last of Us marked the end of the PS3/XBox 360/Wii U era, The Last of Us Part II marks the end of the PS4/XBox One/Switch era, and it’s a lightning rod of many of the conversations that marked that era, and that will mark the next one too.

It’s also as much of a response to The Last of Us as it is a sequel to it. The first game was set in the aftermath of a viral pandemic that turns people into “infected” (read: zombies) and revolved around Joel, a grieving father, and Ellie, a girl who turns out to be the one human immune to the virus. In classic Naughty Dog fashion, it was an incredibly immersive and cinematic experience, with some of the best action set pieces you could ever hope for and some top-notch shooting gameplay. It was also very much a game that was about the cost of life, ending with a crushing blow. Joel chose to save Ellie’s life, by murdering an entire hospital worth of militants who wanted to harvest her brain to develop a vaccine to the virus, and dooming the entire country to post-apocalyptic hell.

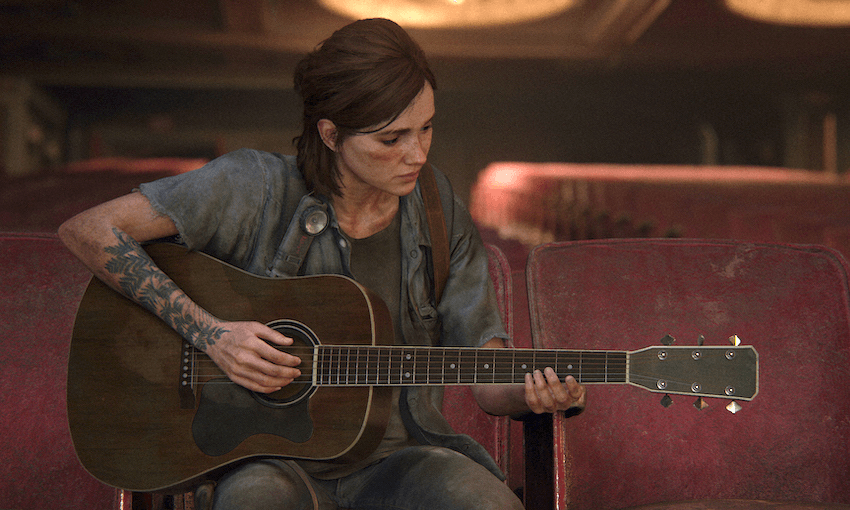

The sequel finds the player in control of Ellie, four years after Joel’s choice. The world is still in the grips of a pandemic, with small pockets of community surviving, if not necessarily thriving. The shadow of Joel’s choice is a spectre that hangs over from the first one, and it’s that choice that eventually sets Ellie off on her path, one marked with violence, zombies and murder. You know, as you expect from the post-apocalypse.

Technically, the game is an improvement in every way over the predecessor; Naughty Dog is very good at making this kind of game (albeit at a cost), and they only make them look and play better. The original game played well when it came out, but gamers expect a fleeter, more reactive experience now, so that’s how Ellie plays. Stealth, already a core part of the first game, is even more crucial here, and so is the need to be reactive to the way both zombies and humans can move. It gives each skirmish a tense fluidity; enemies can flank the player and will change up their tactics depending on what you’re doing. If you play as an Ellie who slaughters indiscriminately and loudly, the game will respond. If you play as an Ellie sneaking her way through, the same. It’s superb, faultless gameplay, one with stronger bones than its predecessor, and it’s the kind of game that will remain fun even as trends march onwards. Even while the game itself can be emotionally gruelling, the gameplay never is.

The game also gets around the fact that post-apocalyptic games can look, well, rather dull. The apocalypse apparently doesn’t just rob the world of happiness, it robs it of colour too. The Last of Us avoided this in a genius way – depicting a country overgrown with green, as though nature wasn’t destroying humanity but actually draining from it to heal itself. The new game takes this further by incorporating snowscapes, a city that seems to be drowning both in despair and literal water, and a hospital so existentially terrifying it could be in the Silent Hill franchise. The one downside is that it’s yet another triple-A game that cribs, liberally, from the western genre for its aesthetics. It makes sense, given the actual setting (the very literal west of the US), but it does make me wish that some of the most talented visual artists in gaming were given scope to work with a wider palette.

For a game that can be so hard, emotionally, to play, what’s most remarkable about it is how Naughty Dog have made it easy to play. The accessibility options are amongst the most incredible I’ve ever seen in a video game, with extensive options available to people who are visually or aurally impaired, and even options to relax the game, making combat much easier (one option lets you be entirely invisible if you’re crawling) and navigation a lot simpler. With the right options toggled, someone who is entirely deaf or blind could play the game with no barriers. As much as the game seems to punish emotional investment, The Last of Us Part II is clearly a game that wants to be played, and played with as much engagement as possible. The bar is now set, and other games shouldn’t just hope to reach it, but should be required to do it.

A lot about The Last of Us Part II will make the worst people on the internet angry – the kind of people who are angry not just that the main character, Elle, is queer, but that she’s supplanting the first game’s Joel, who looks and sounds like scores of men at the centre of gaming’s most recognisable titles. But let’s not worry about that anger, it will come and go. Instead, let’s focus on Ellie, easily the most prominent queer character in gaming (with the exception of BioWare games and their opt-in queerness), and that queerness is very much front and centre. She has a girlfriend, they kiss, they have feelings and everything. It’s groundbreaking for a game of this scale to do romance well, for it to do queer romance well is nearly unfathomable.

The game also treads the line between being noticeably diverse and effortlessly diverse; the former only because of how badly every other mainstream game does in this regard. It’s maybe the first mainstream game I’ve seen where the cast actually reflects reality; everybody, regardless of how they look or sound, is written as a fully-realised human that has a life even when they’re offscreen. Naughty Dog spins this particular plate very deftly; the developers practice deliberate inclusivity in such a way that even the most critical (read: bigoted) eye couldn’t call laboured or pandering. It’s a masterclass in how gaming can do inclusivity, and, similar to its approach to accessibility, it sets the bar for the rest of triple-A gaming. It shouldn’t be a hope, it should be a requirement.

That gets us to another issue of tension around The Last of Us Part II. While it’s an incredibly immersive and engaging experience with some of the most robust running-and-gunning I’ve ever played, it can also be an incredibly punishing experience, emotionally. This is not a happy game, and it’s a game that goes to lengths to punish happiness and complacency, whether it’s punishing the characters or the player. The saying goes, “No matter how dark the night, morning always comes.” Naughty Dog flips that; no matter how light the morning, night always comes to shit on it. It doesn’t lessen the brilliance of the gameplay, or how well written and structured the narrative is, but it leads to a monotony that dulls everything a bit down. When you know that things aren’t going to get better for anybody in the game, just progressively worse, it makes any of the game’s observations or brilliances feel hollow. It’s very hard to see shades of grey if all you’re looking at is darkness, and you cry hardest after smiling.

It’s a darkness that’s inherent to the setting; a post-pandemic apocalypse is hardly the best foundation for a cheery comedy. That darkness is also inherent to the game’s genre – a run-and-gun survival action gamer is also not necessarily the best foundation for a cheery comedy. There’s only so much exploration can do within such tight confines, and this extends to the kind of thematic material that Naughty Dog is able to explore with the game. I’d love for the game to explore Ellie’s queerness more, or the inner lives of the rest of the cast, but a zombie apocalypse isn’t necessarily the best or most effective place to do so.

What the genre does lend itself to is an exploration on the nature of violence, so much so that addressing it feels obligatory rather than intentional. The Last of Us is a violent series, by design; the gameplay in its entirety is about traversing a post-apocalyptic world full of starving infected and murderous humans and doing so in a murderous way. It’s even unavoidably violent; while the player can get through the game only carrying out a handful of violent acts, that’s unlikely, and the game still depicts violence in such a way that it feels like it’s being forced on you, rather than a choice. It’s as brutal as the violence I’ve seen in any game, made even more so by the realistic graphics and the ultra-present soundscape.

The story presents the cycle of violence as a choice, one that circumstances lead the characters into, but the player is only given that choice occasionally. It dulls the potency of the message when it feels like it’s the only message the game can have and still justify its violence, and frankly, the audience’s expectations. Naughty Dog clearly set out to make a game with thematic heft, and there’s no way to do that within these confines without justifying, or at least addressing, the violence inherent to it. This isn’t the Uncharted series, which can play off Drake’s mass murder as swashbuckling fantasy. If they want to make The Last of Us Part II a game that means more than a zombie murderfest, it needs to address violence.

Which, despite genre forcing the game’s hand and the game forcing the player’s in turn, it actually manages to do pretty well. Violence is a well-trodden theme across nearly every art form, and gaming is an especially fitting place to explore it. It’s one of the few forms that lets you actually enact violence, and feel the thrill/horror of it (depending on the game). If you do choose to play this game murdering everybody you come across, you’ll hear your enemies yell out the name of their teammates, reinforcing the fact that these are real people. The narrative of the game also enforces this kind of acknowledgement of real people; your enemies are not faceless mooks, they’re people who you care about. Sometimes the game can go a bit overboard with this – dark at the expense of depth, edgy at the expense of subtlety – but when it works, it’s effective as hell. Naughty Dog clearly wants to interrogate the violence they’ve built their two latest franchises on, and it’s not a moment too soon.

To put it generously, The Last of Us Part II carefully treads more than a few difficult lines – the line between representing queerness and centring it, the line between choosing to be about the cycle of violence and being forced to address it, the line between being an immersive experience and being a punishing experience. The fact that it’s doing any of these at all is admirable. To put it less kindly, and realistically: The Last of Us Part II is right in the middle of many unwinnable battles, and like its protagonist, it comes out winning, setting bars across the board, but definitely not unscathed. There’s only so much you can do when you’re bound with the restrictions of not just your genre, but by the expectations of a triple-A sequel to one of the most critically acclaimed games of all time. So while it sets all those bars, what I think the lasting legacy of The Last of Us Part II will be, rather than an incredible sequel to a much-loved game (and there’s no question, Cyberpunk 2077 pending, that it’ll be getting dozens of game of the year awards), is that it will go down as a lighting point for conversations. Conversations around accessibility, around representation, around violence in video games. They’re important conversations to be had, and it’s long overdue for them to come from the fringes into the mainstream, and a credit to The Last of Us Part II that it’s a lightning rod for what it is doing, rather than for what it’s not.

Some games are great because they play well and they’re fun. I think The Last of Us Part II plays well, but is not especially fun, and I think it’s a game that does not want to be fun either. Other games are great because they change the way we talk and think about gaming. The Last of Us Part II will be that game for a huge amount of people, perhaps millions, and for me, that’s what makes it great.

The Last of Us Part II was played on a review copy provided by Sony, and was completed once.