Why osso buco is on the menu this week.

This is an excerpt from our weekly food newsletter, The Boil Up.

One of my earliest food memories doesn’t involve me eating at all – only the unrivalled joy of watching two plump middle-aged men cook and taste their way around Italy on the BBC series Two Greedy Italians.

In our home, Antonio Carluccio recipes are bible, but onscreen, Gennaro Contaldo is my favourite. The way he exclaims “look how beautiful!” as he unwraps the meat, “oh my gosh, oh my my, that is so good, yeah!” as he scrapes the caramelised bits from the bottom of the pan, stirring them into his soffrito. His enthusiasm is infectious, as is the way he handles his ingredients in a manner simultaneously utilitarian and reverential: “good salt” sprinkled liberally on meat ribboned with fat, “stock is important” he tells the camera solemnly as he pours golden liquid into a steaming pan.

The video I am describing is actually of Gennaro on Jamie Oliver’s channel (he’s the one who taught Jamie to cook Italian food). And the dish he’s cooking? Osso buco, my plan for dinner on a stormy Wednesday night.

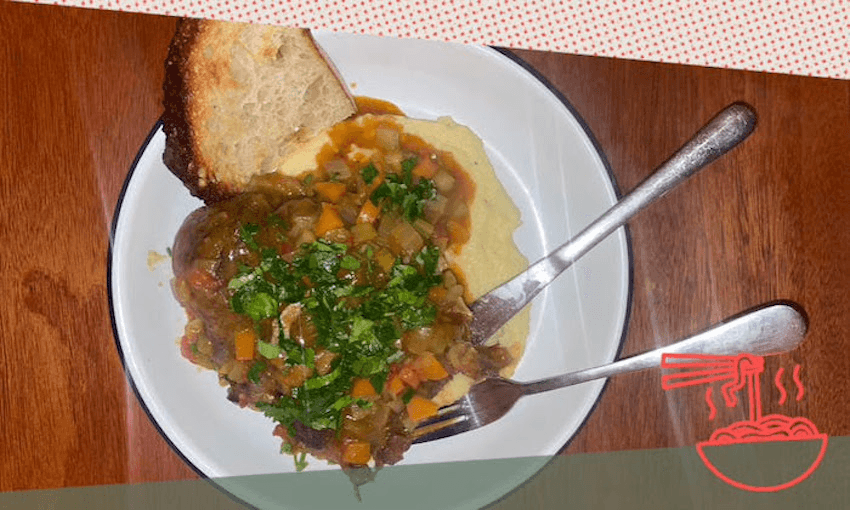

If you’ve never had osso buco, do. As Gennaro explains, it is a classic cucina povera dish, a rustic way of cooking developed by Italian peasants to create maximum flavour despite a paucity of ingredients. Traditionally made of bone-in veal shin, osso buco is braised low and slow with onions, white wine and stock – the other ingredients and details vary from region to region, chef to chef. Gennaro’s recipe is a Tuscan one, and so he adds carrots to his soffritto as well as tomato passata. For mine, I added a rib of celery and used rosé in lieu of white – sacrilege to some, but in the spirit of cucina povera, given I had a bottle already open.

While osso buco is no longer the cheap cut it once was (due to the worldwide popularity of what was once a meal eaten only by the rural poor), cooking it did remind me of this underlying philosophy of cucina povera: use what you have, cook it with love and care, and turn what might otherwise be wasted into an opportunity for flavour. At its heart is creativity and the understanding that eating well has any number of definitions. In this seemingly unending cost of living crisis, we can glean a lot from cucina povera – below are some of the lessons I’ve learned.

- Value the ingredients you have, plan thoughtfully, cook carefully.

- Don’t demonise carbs. Pasta started out as a cucina povera food, mainly in the south where it was made without eggs, simply flour and water. Stale bread was never wasted, turned into dishes like panzanella while breadcrumbs used to stuff vegetables or coat foods for frying. Polenta, rice and potatoes (including gnocchi) were also staples of peasant cooking, used to stretch meals further.

- Embrace pulses! Tinned beans and lentils are excellent in a pinch, but dried lentils are extremely economical, nutritious and delicious. Italians love thick, bean-based soups and each region has its own version of pasta e fagioli (pasta with beans). Add pulses to any soup to boost the portion and the protein.

- Buy cheaper cuts of meat (including nutrient-packed offal) and cook long and slow with bases of sautéed herbs or tomatoes and black olives.

- Preserve! Back in the day this looked like drying, salting and curing meat and fish so it would last longer – think capocollo (that’s gabagool to the Sopranos-heads), mostardella (made from leftover pork and beef combined with aromatics), but also baccala’ (salt cod) or stoccafisso (air-dried cod). For us, this might look like buying in bulk when ingredients are cheap and freezing, or making pickles or ferments with fruit and vegetables you might otherwise not use up.

… and if you do make osso buco, don’t forget to scoop the buttery marrow from its bone – it’s the best bit.