Auckland fish and chip shop Marsic Bros opened its doors in 1967. After 55 years of deep frying, the owners share some of their insights on the art of fish and chips.

Number 92 is announced from behind the till. A beaming customer steps up to collect their order. Marsic Bros Fish Shop in Glen Innes town centre has been serving fish of all kinds since 6am (yes, you read that right); they’ll close tonight at 6.30. It’s just past three and the shop has a steady stream of customers picking up fish and chips, fresh fish and their signature “all natural” smoked fish.

Passersby peek through the front window to survey the cabinet that today is filled to the brim with smoked mussels, salmon and roe, punnets of raw fish, and whole and filleted fish of various species. You can buy fish heads or bags of fish bones for $5 too, but today, I’m here for the classic: fish and chips.

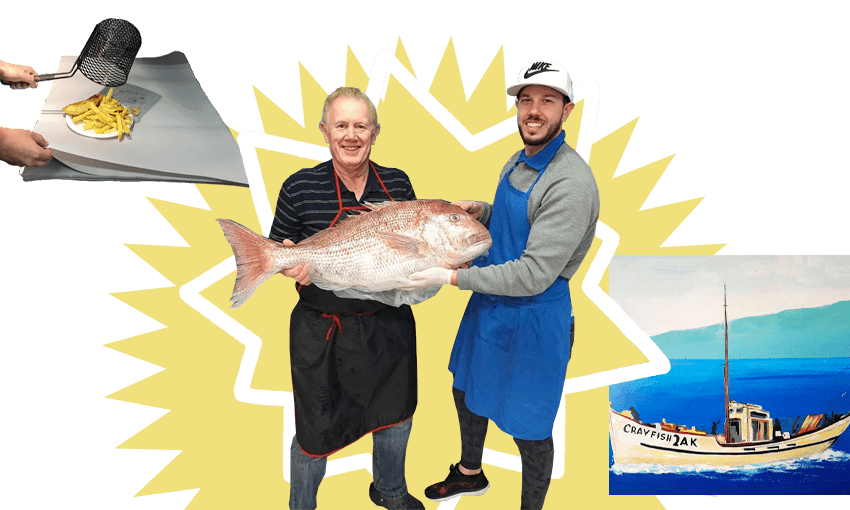

Marsic Bros was opened in 1967 by brothers Wally and Ivan Marsic, both born and raised in Croatia. It’s still a family affair. Ivan has now retired, but he still pops in to help out. Wally’s son Daniel and daughter Stephanie have joined the business and other family members and friends help out when there’s a need. Wally, now 74, is up at 3am most days of the week to buy fresh fish for the day from the central city fish auction or to smoke fish out the back.

When the shop was first opened, it was flanked by Samuel’s General Store and a hardware shop. Back then, Glen Innes was newly established as a hub of state housing, and eventually had the highest density of state homes in the country.

Despite Croatia being a nation of seafood, fish and chips was an unfamiliar dish to Ivan and Wally when they first moved to New Zealand. Mastering the art of deep-frying relied on shared knowledge among the local Croatian community, as well as some friendly competition from other Croatian-owned fish and chip shops. Fish and chip shops became a way for immigrants at the time to establish themselves in a new country, explains Daniel Marsic.

Things have changed in Glen Innes more recently. The suburb has been a focal point for discussions around gentrification in Auckland, especially since the controversial eviction of more than 180 families from their long-term state homes between 2012 to 2018 as part of a regeneration plan. Despite these upheavals, for now at least, the eastern-fringe suburb has retained its diversity and vibrancy.

Fish and chips is an extremely democratic dish, explains Daniel Marsic. It’s not unusual for tradies in hi-vis, pensioners, high-school students and local politicians to be standing shoulder to shoulder (or perhaps more socially distanced these days) as they wait eagerly for their number to be called. At the end of the day, they’re all eating their dinner off a piece of newsprint.

At Marsic Bros, the deep fryers start cranking at 6am. “We do a lot of preparation in the morning,” explains Marsic, “so my dad and uncle have always figured, ‘oh well, you might as well be open and make some extra money’.” At that hour of the day, customers are often workers on their way home from a night shift, but also people who just feel like a steaming parcel of chips to start the day – and they sell an incredible amount of hot chips in winter. Assumptions around the nutritional merits of fish and chips aside, the shop offers food as fuel, a meal cooked with care for people who work non-standard hours and have limited eating-out options.

Customers are mostly locals, but some will make a mission across town. “Especially some of the roadwork boys that have been up all night,” he says. “Some of them come out just from out west or out south to get a feed.”

The diversity of the suburb is reflected in the lack of wastage of fish by the shop. “That’s what I really do like about GI,” Marsic says. “Where one group of people might not eat a particular part of the fish, it’s a delicacy to other people.

“You look at the fish as a whole, like a snapper,” he says, making the outline of the shape of the fish with his hands. “And really, by the time we’ve dealt with it, there’s nothing left, the only thing that’s left is what’s inedible, which might be the guts.” Even then, that might be used for bait or burley, instead of being tossed in the bin. This has benefits both culturally and environmentally, but low waste helps to keep costs down for the business and their customers too.

The mathematics that take place in a fish and chip shop when it comes to pricing or portion sizes are pretty mysterious, Marsic admits. But in essence they’re equations of fairness. Daily decisions like judging what constitutes a scoop of chips, or what $4 worth of chips means in practice, or the price for a piece of deep-fried gurnard, simply come down to being reasonable, he explains. For example, when it comes to the elusive nature of a scoop, “one scoop of chips would be a good feed for one, but not enough to put you to sleep”. If you want to feel sleepy after your meal, Daniel recommends ordering one-and-a-half scoops or maybe even two.

Beyond the basics – like having clean fat, good-quality fish, cooking at high temperatures and draining the food – there are no real trade secrets to good fish and chip shop deep-frying, says Marsic. Instead, it’s all about consistency.

“The hardest thing is people’s expectation on what they think fish and chips should be,” he says. Their dedication to precise consistency, which has kept the shop afloat for 55 years, means customers know exactly how to communicate whether they’d like their order crispier or soggier than normal.

There’s a pressure in maintaining consistency in a food business that’s been open for so long – a rarity in the fickle Auckland hospitality scene. Physically, Marsic Bros’ ties to the past are manifested in old hand-painted signs, the mural on the shop wall, the walls of the smokehouse tarred black from years of use, and an ancient-looking metal electric potato peeler that Marsic reckons could be almost a century old.

Marsic Bros customers often grew up eating food from the shop, and come in for a taste of their own history. The family is dedicated to maintaining that steadiness and recognisability, and they know how important it is to their customers. “If we turn into a real slick commercial type thing, it would kind of lose its charm.”

The importance of maintaining that charm has been underlined by the pandemic. Since the beginnings of Covid-19, some have noted that our taste in food has been leaning toward nostalgia. Essentially, there have been suggestions that we seem especially drawn towards the meals we ate as children – a literal taste of the “idealised” time before the pandemic. Marsic agrees and says more than ever, customers seem to relish the experience of tasting something from “back in the day”. Within a New Zealand context, fish and chips might offer familiarity in a time that is largely uncertain. Even more so because it’s a dish shared across different generations, class groups and ethnicities. “Maybe when things slowed down it gave people the chance to think about how they spend their time, too,” he says.

In a more practical sense, fish and chip shops provide a safer form of dining out in that they’re made to be taken home, eaten at the beach or even off the car bonnet – which “makes the fish and chips taste even better”, says Marsic

Is deep-frying fish, chips, hotdogs and oysters an art, though? Marsic thinks so. “Everything’s got an art to it, doesn’t it?”