It was founded in 2022 with big dreams to explain the centre right’s worldview to New Zealand. Then in September last year, it abruptly ceased publishing.

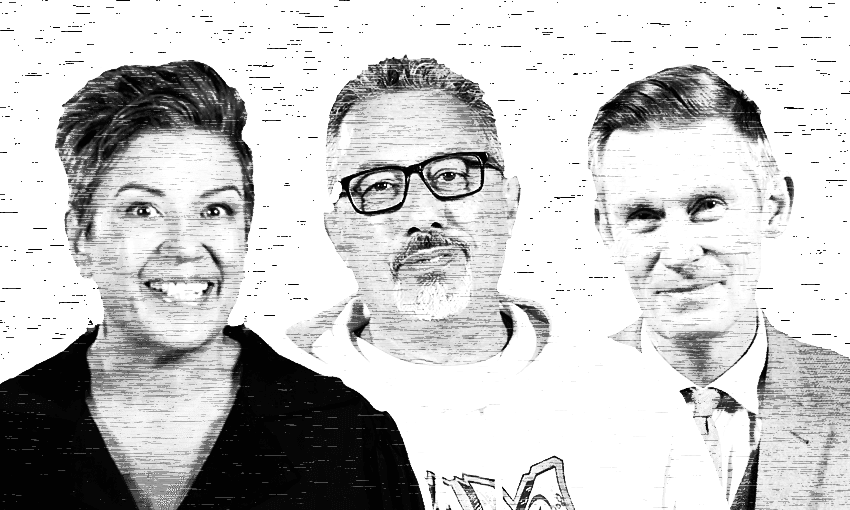

In the first of a new bi-weekly media column, Above the Fold, Spinoff founder Duncan Greive tracks down the founders of The Common Room to find out why the popular platform slammed to a halt.

August of 2023 should have been a period of huge excitement for the backers of The Common Room, a new right-leaning media platform aiming to bring socio-political views that its founders felt were missing from the mainstream discourse, wrapped up into slick videos made for social media. They wanted to advocate against hate speech laws, for being tough on crime and gentle on farmers – fairly generic conservative positions, delivered in punchy five-minute clips.

The election was looming, which always causes a surge in interest in political content, and they were well-placed to leverage that into expanding their audience. This is because the specific issues the Common Room wanted discussed had become very present in the campaign, with co-governance, growth in the public service and inflation all subject to vigorous debate, driven largely by the Act party and a resurgent NZ First, having come from nowhere to impressive polling numbers.

On August 27 the Common Room sent out an email promoting a video starring Josie Pagani, a former Labour candidate and Alliance press secretary. The video asked “should we ban offensive words?”, spurred by the move to delete certain passages deemed offensive to some from new editions of Roald Dahl’s novels. Pagani is often shorthanded as a left-leaning political commentator but, like fellow travellers Martyn “Bomber” Bradbury and Chris Trotter, she has drifted from favour due to scepticism of the modern left’s intersectional analysis of inequality, emphasising race and LGBTQIA+ issues over class and income.

Pagani’s video fit squarely into the Common Room’s approach, describing what she felt was overreach on the part of Dahl’s publishers, Puffin, in removing phrases which have over time become offensive to some modern sensibilities. “This is about freedom of speech and artistic expression, not sensitivity”, she said, while a cartoon chainsaw hacked through some cartoon books. There was nothing about it which suggested anything other than business as usual for the Common Room.

The following week though, there was no email. Nor the next week, or the one after. Their once bubbling social channels were silent too, as was a website which had recently been regularly publishing or syndicating content from the likes of then-anonymous Substacker Thomas Cranmer (since unmasked as lawyer Philip Crump, now installed as editor of ZB+) and Graham Adams, the former chief sub editor at Bauer media who has become a popular and stinging mainstream media critic for a variety of right-wing platforms.

The election came and went without a peep from The Common Room. On October 29, I texted Lou Bridges, the Common Room’s co-founder, asking what was going on. She replied saying “we are taking a break for a bit”. When I asked if she or her co-founder and The Common Room funder Mike Ballantyne would explain why, she declined.

Within a few weeks, the coalition had formed. Its chaotic beginnings were covered in granular detail by a whole panoply of right-leaning media platforms, including a number of which had started within months of The Common Room. Many had a somewhat triumphant attitude toward the end of the Labour government’s approach to race and justice. But the Common Room’s more cautious and slow-burning content was nowhere to be seen.

An empty space

For decades the idea that there was room for a right wing media ecology to develop would have seemed fanciful. The mainstream news media, in New Zealand and elsewhere, seemed to exist to reinforce much of the status quo. It reported breathlessly on crime and was suspicious of activists and those who sought to disrupt majority consensus views of society. Columnists were almost all older pākehā men, typified by the likes of Michael Laws, a Stuff columnist who wrote widely and angrily about Māori and women and referred to “Chow-ick” and “Paku-langa” in asking questions like “Do we want more Chinese and oriental Asians, or do we not?”

Over the last decade, that has shifted. Our biggest newsrooms are younger and becoming more diverse. The coverage they create is more likely to embody a progressive worldview than in decades past. Most have dedicated te ao Māori sections and reporters. The Herald’s “protest free zone” Waitangi Day coverage of 2014 is fairly unimaginable now. Most emblematically, you can see the way John Campbell’s columns, stridently and unequivocally critical of the new government, are now given the prominence befitting his title of chief reporter at TVNZ. Two decades ago his equivalent north star of journalism and commentary was Paul Holmes – a brilliant broadcaster, perhaps our best, but a flinty centre-right populist too.

The news media has been dealing with declining revenues and a squeeze from social media platforms, but has certainly trod lightly around certain coverage areas, from trans rights to co-governance to the economic impacts of extended lockdowns, all of which had sizeable constituencies extremely interested in them. This sense of an absence is what drove the establishment of a significant number of new right-leaning publications, most of which were created by people mad that an issue they considered very important was being under-covered or ignored by mainstream news media.

It’s worth listing them off, because the sheer volume of launches is quite staggering, for a small country – and there has been no equivalent flowering on the left. A small sample: The Platform, founded when Sean Plunket was forced out of MediaWorks. Centrist, which bundles doctrinaire right-wing talking points with a fixation on “vaccine injuries”. Bassett, Brash and Hide, where three former senior Pākehā politicians talk often about Te Tiriti. Reality Check Radio, founded by anti-vax wellness influencers with former TVNZ broadcaster Peter Williams prominent. The Daily Telegraph, which features a grab bag of anti-vax content, free Julian Assange content and Russian propaganda. And The Facts, which aims for a firm research basis but has a clear ideological through-line.

The outlier

Then there’s The Common Room, the most mild-mannered and sober of the lot. It debuted in August of 2022 with a video from former deputy prime minister Paula Bennett explaining her journey to right wing politics. In the following months it put out dozens of tightly-edited videos, featuring an array of commentators (notably a good many National and Act politicians), espousing perspectives which expressed mainstream right-leaning perspectives – small government is good, inflation is bad, the bureaucracy is too big. Over time, along with its weekly videos, it published a number of written pieces, which its founders say performed very well for the site, but still largely stayed within its lane.

I found its approach refreshing, and sharply contrasting with the often inflammatory tone of its competitor set, and kept pestering them to talk about what had happened. I finally convinced its founders to meet in January of this year, and they told me that it shut down for two broad reasons. The main one was a sense that New Zealand’s politics and media had become more open to the kind of debates they felt were missing from our discourse.

“I think that a lot of these things that were off the table suddenly came on the table, during election year,” says Ballantyne. “Co-governance would have been one. The size of the bureaucracy, the amount of spending. A lot of that stuff suddenly started to come under the spotlight. Even some of the stuff around free speech and hate speech laws. We’ve gone from a period during Covid, where it was very controlled or felt very controlled. But around the election that seemed to open up and it did open up. I was quite surprised by what was being published.”

The second reason for its cessation was financial. Ballantyne, the main funder, had burned through the money he had allocated to it. He did have conversations with a number of other individuals who admired what he was doing, and expressed an interest in helping contribute to it financially. Yet when they had more substantive discussions he felt their motives differed from his own in crucial ways. “I think it dawned on us pretty quickly that there were strings attached with any money that you bring in.”

Those potential funders would have pushed to open some doors Ballantyne felt were better left closed. He’s opposed to a referendum on te Tiriti, and believes many of the divisive, hot button issues of this era are better left alone. “We didn’t want to get into the whole vax debate,” he says. “We didn’t want to get into transgenderism. Lately, the whole Israel-Palestine thing.” Those issues prompt huge cut-through but are also deeply polarising, where Ballantyne and his co-founder Lou Bridges believed reasoned debate could help heal divisions.

The gap it leaves

Others in and around the right-leaning commentary sphere, who contributed to the Common Room, uniformly mourn its loss. “I feel sad about this as one of their earlier contributors,” says Liam Hehir, author of the Blue Review, a popular conservative-leaning Substack. “The New Zealand media market is so small and the political media market smaller still. But they can be rightly proud of producing good, professionally made content that didn’t go down the easy route of just trying to make people mad.”

Sean Plunket (who expressly denied that the Platform had any political leaning), was similarly complimentary, while expressing doubts about their business model. “General impression was they were committed to their ideals but probably weren’t planning a sustainable media business.” Philip Crump, who started a popular Substack under the name Thomas Cranmer before being recruited to run the ZB+ commentary platform, described it as “a high-quality and innovative operation which addressed topical political issues, privately funded on a not-for-profit basis,” adding that “it was a popular and useful addition to the pre-election conversation”.

Popular, perhaps – but not popular enough. Bridges says that the noise of the election felt like it overwhelmed their slower-cooked content. She says as it drew near, they felt their “content – being much longer lead time, thoughtful, crafted – it wasn’t going to fly in that really busy space. A lot of the more centre right media voices started posting and publishing several times a day.”

That wasn’t something they felt capable of doing, so when the first tranche of money ran out, Bridges and Ballantyne had a conversation and decided to let it lapse. They were satisfied with the numbers, which ranged from the hundreds to the thousands on their videos, but didn’t feel like the cut-through was sufficient to justify the investment. Ballantyne says he was disappointed to discover that “the average punter doesn’t engage – doesn’t really think deeply about our political system, the power of their vote.”

In some ways their agreeable, even-handed version of conservative thought felt slightly anachronistic in the hyper-partisan world we live in. Election campaigns have a frantic, high stakes energy at odds with the contemplative nature of their videos. The surviving right-leaning platforms (and the granddaddy of them all, Newstalk ZB), all make their bones with high volume, specific and pointed content. The Common Room is consigned to history as an experiment which never quite found an audience large enough to justify its considerable investment.

For Ballantyne though, it still scans to him as a worthwhile experience, one which taught him something about the media, and brought him into spheres he would never otherwise have encountered. Bridges, for her part, would do it again in a heartbeat, and says friends told her its work changed their minds. “We did something,” she says proudly. “And it would have made a difference somewhere.”

Follow Duncan Greive’s NZ media podcast The Fold on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts.