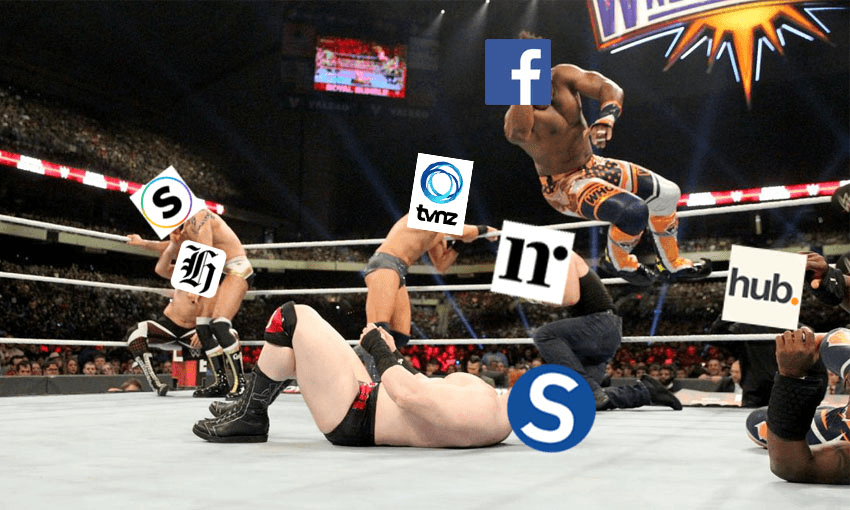

A just-released cache of Nielsen data shows the impact a series of Facebook algorithm changes has had on New Zealand’s online media (spoiler: it’s not great).

“How’s your traffic been?” a friend who works at one of the big media companies asked me recently, and even in asking we both knew the answer. It was late July, and we were coming off the end of a near month-long chill. I told him what he already knew: that it had been a slow month.

For 20 straight days we didn’t crest 60,000 pageviews – our marker for a good day – even once. It had come from nowhere: between the start of June and July 3rd we had 10 days over 60,000, and a pair just shy of 100,000. Our simultaneous on-site number sat in the 200s for hours on end, and pieces we had been certain would become huge hits seemed to start trending down far faster and harder than we had anticipated.

It breeds a kind of neurotic angst – always an occupational hazard in this industry – in editors and journalists. A paranoid second-guessing of what might be the cause. Have we lost our edge? Has all the negative coverage of our TV show (a note on that at the bottom of this story) impacted the site? Are people just sick of us now?

“I bet it picked up about 10 days ago,” he added. “Facebook eh,” he said, shaking his head. And he was right, it had. I felt the relief of a problem shared and halved wash over me. The answer was what it always is: Zuckerberg had tweaked his algorithm again.

Facebook is the great equaliser of online media in New Zealand and just about everywhere – this mighty wind which rears up from nowhere, without warning or reason, that we all feel in our bones. While The Spinoff is still young, still not yet four years old, we’ve been around long enough to know what these swings do to your traffic. They don’t decimate it – just take the top off it. Take the edge off a big story, and keep it from running nearly as long as it would have in the past.

Zuckerberg’s creation arrived with this extraordinary message for publishers: we are where everyone is. Build audiences here and your best work will find its way to the right people. It promised a seductive democracy – that on Facebook, we were all a lot more equal. A terrific story could circle the world from anywhere.

A classic example was Toby Morris’ ‘on a plate’ Pencilsword comic. It went viral globally, gaining two million views for The Wireless, a further two million on Imgur and coverage on many huge international sites on its way to being translated into 10 languages. (By way of comparison, the biggest-ever post on The Spinoff – Lucy Kelly’s first person account of working at an abortion clinic – has had 500,000 views.)

Audiences, too, were told Facebook was the internet (in large chunks of South-East Asia this is literally true: it provides the internet and the platform is the only available product) – that you should go there for everything from funny videos to keeping up with family to buying second-hand cars to knowing what to do this weekend. Along with being the best place to consume journalism about what was happening in the world and your neighbourhood.

You know what happened next. Trump happened, and Brexit, and Cambridge Analytica. Suddenly Facebook couldn’t stand the heat, telling publishers that they were about connecting friends and family and that they had little to offer them.

The first of many hard algorithm adjustments hit last year, and they have come sporadically ever since. January saw a major shift toward ‘friends and family’ content and the suppressing of video – which went from a privileged form to just another post.

The only thing certain in this strange world is that whatever the current situation is, it won’t last long. The opaque dictatorship is the new reality for media, and if it can swing elections and referenda without major commercial consequence you can be sure that the fate of New Zealand’s national media organisations is not high on its priority list.

To illustrate the point, an explosive recent report in the Guardian, from a round of consultation New Zealand media also attended, quoted the brutal carrot and stick: a Facebook exec telling media that Zuckerberg didn’t care about them on the one hand, while also balefully threatening firms which didn’t collaborate with the “hospice”.

It’s a real scene out there.

This matters because training the media to find people through Facebook also trained people to use Facebook to get The News. But because it’s just another item in the feed, who could tell if the frequency with which you see news dials back from one post in eight to one in 12? Or in 20. It just gradually slips away.

The problem is we have long relied on the internet to ultimately save the media. Trends around legacy media distribution channels are well established – newspapers are fading, magazines are fading, linear TV is fading, radio is somehow hanging on. Those behaviours aren’t coming back: younger New Zealanders aren’t going to magically hook up their TVs and start buying the paper. Even Sky, the monster of subscription linear TV, is openly talking about its end. The bright spot, the future – that was the internet. With Facebook the biggest driver of them all.

The idea was that we were at the start of the curve. That as these legacy forms trended down, the internet would trend forever up. That audience significantly outpaced revenue was not ideal, but so long as the audience was there, the idea went that the revenue piece could be figured out.

This is why you saw investment flowing into digital even as it continued to lose money. NZME has just this year launched YUDU for jobs and OneRoof for houses, while Stuff now wants to sell you broadband, electricity and movies. Chaos – but a beautiful, exciting chaos; an unmapped future replete with possibility. We were only working out the detail.

What I’m about to do is pivot – a classic internet move – to statistics. To data. Online stats are not regularly reported on – to find numbers of any kind you kinda have to follow the right people on Twitter, or perform educated guesswork through services like SimilarWeb.

It’s complicated, and the numbers are difficult if not impossible to compare across platforms. My favourite trans-media survey is Glassdoor’s epic biennial work for NZ on Air, which seems the most non-partisan and was just released last month. It’s New Zealand’s little brother to Mary Meeker’s much-followed annual Internet Trends data dump and shows that many of the forces at work here are truly global ones. Still, ultimately it’s genuinely very difficult to count between different media forms.

But within online media? That’s not hard at all. And while all online media companies collect their own data, all of which is as close to perfect as any in the industry, it is only rarely and very fragmentarily released.

Until today, when Nielsen released a parcel of data which, while limited, is also richer than any we’ve had in public for a while. Here are a few key statistics from it, which show how a basket of local media organisations are doing online.

A caveat: the stats Nielsen released are confined to two organisational categories, and thus arbitrarily exclude some key NZ media (I’ve worked around that by adding them in in places, where the data was already public). And it’s worth remembering that most news media are broadly defined by pace (Stuff publishes roughly twice as many stories in a day as we publish in a month, for example) and by style (the Herald, Newshub, TVNZ and Stuff tend towards briefer, newsier content; The Spinoff, Noted and Newsroom towards longer pieces leaning into analysis, opinion or feature writing).

I’ve broken the second set of stats up into two groups: Stuff and the Herald versus The Rest. The big two have an enormous lead over the rest of the online media, to the point where graphs start to look pretty screwy with them involved. With that in mind, here are some insights into how the online media in New Zealand is currently performing, broken down by a few different metrics.

[Spinoff app users click here]

Monthly Unique Audience is the industry standard

This is one of Nielsen’s core online measurement metrics – it’s aiming for unduplicated reach which can be used for comparison across different media. Its methodology is not dissimilar to the way TV audiences are surveyed, in that it is a measure of actual viewing versus claimed behaviour – in the online case, data is collected from a panel of 3,000 people, balanced for demographics, monitored constantly – which is probably part of the reason they recommend it for market comparisons. (It doesn’t currently measure mobile apps – which now represent around 10% of our traffic, for example – though that tech is coming soonish).

The above chart is made up of the newly-released Nielsen data combined with other Nielsen data released by journalists prior to now. It broadly shows a series of battles of different scales: Stuff and the Herald at the top, Newshub and TVNZ a few rungs back, RNZ on its own in fifth before a chasing pack running from regional monster the Otago Daily Times on 220,000 down to the NBR at 75,000 (very respectable for a largely paywalled specialist publication).

Unique Audience is the most commonly reported number. It aims to cut through the multi-device noise, which might see the same person appearing as three different IPs (desktop, laptop and phone) and give a real humans number. It’s also worth noting that online traffic is unlike broadcast audiences – it starts revving up around 7am and stays strong through the late evening. There is no primetime. While it’s a useful metric, it’s interesting to see how it rubs up against a few of Nielsen’s others.

[Spinoff app users click here]

Daily unique browsers is a proxy for loyalty

Visiting a site once a month is not a particularly committed act. Visiting each day implies a far more serious kind of relationship. The daily data is harder too – rather than being extrapolated and demographically calibrated from 3,000 people, it’s the raw numbers from the on-site pixels. So they will be inflated to an extent by multi-device/multi-browser users and cookie deletion, but the narrowness of the time period should keep a lid on that.

It also shows just how extraordinarily dominant Stuff and the Herald are by comparison to the rest of the New Zealand online media. Each are north of a million unique browsers a day. Yet Stuff’s lead over the Herald starts to look really intimidating – it’s nearly half as big again as the Auckland-based powerhouse on a daily basis. This shows the value of the early commitment to online, as well as truly national coverage.

Frustratingly Nielsen’s categories keep some key sites like RNZ, Newshub, TVNZ and the NBR out of this release, but data seen by The Spinoff shows Newshub has a small lead over TVNZ with each well over 200,000 a day, while RNZ has a very steady audience of over 100,000 a day in fifth.

The figures also show a bigger gap between the ODT and The Spinoff than the monthly figure might indicate, and that both ZB and BoP news site Sun Live (which I confess to having never knowingly read) have significant daily audiences.

Further down we see that the relatively recently launched Noted (German publishing conglomerate Bauer’s home for Metro, The Listener and North & South’s work online) and Newsroom have relatively small daily audiences, showing the challenge of building committed audiences at scale from standing starts. Newsroom’s is of particular concern – after a strong debut last year its daily audience has halved in the past nine months.

[Spinoff app users click here]

Monthly page impressions is (often) a proxy for revenue

The big one. For the giants of the industry, this is the largest part of their digital revenue. Page Impressions create ad impressions – the more you have the more you make. Here again Stuff shows just how enormous it is: over 50% more views than its nearest rival at the Herald.

The dropoff is steep: Newshub in third has less than 10% of Stuff’s page impressions (though it likely plays a higher percentage of video, which is a more lucrative ad placement). Sun Live and the ODT show the value of a committed regional audience.

In the magazine-style space, The Spinoff has a sizeable lead over the more recent startups Noted and Newsroom, with more than twice as many views as the pair combined.

It’s important to note the incentive structure at work here: Stuff, the Herald, Newshub and the ODT all derive a majority of their online income through CPM-based advertising (in which page impressions are all) – this plus time on page are the big KPIs. None of the big media companies has a paywall, though the ODT announced one in 2016 (it’s still not implemented) and the Herald has signalled one coming later this year – the NBR is the only publisher at scale which has made one work. The Spinoff and Newsroom have very similar funding models – partner content and audience contributions, with the latter having a ‘Pro’ email service which isn’t captured through these metrics. Noted has a combination of advertising and user contributions.

Time reveals all wounds

Page impressions are likely the firmest metric we have online – triggered by a discrete event. Time is the hardest. Read later apps, a row of open tabs, single-event sessions, plain old making a cup of tea while your laptop screen sits open – there are any number of social and technical reasons why this remains hard to measure. Of course, that’s even more true of other media too: the idea that the television has your rapt attention while ads play is farcical; the idea that you can truly know the extent to which a magazine ad or a bus back drives a future purchase decision sillier still.

Yet because digital is inherently more measurable it is often held to a different standard than traditional forms. Still, that’s a perennial complaint from digital media, and these numbers are at the very least comparable within types of digital media.

Stuff remains predictably at the top, yet its margin is significantly trimmed. The Herald’s larger and earlier investment in both an investigative unit (leading to longer-form stories of national significance) and, perhaps, an emphasis on volume video through NZH Focus and the likes of Mike’s Minute (itself often 2-3 minutes long) could each have played a part in reducing Stuff’s total time lead from what you might expect. It also has a market leading 3:08 per session duration, and a Herald source says the publisher has shifted from views to engagement as the key metric as it prepares for its paywall launch.

Thereafter it flows largely as expected – the only major outlier being Newsroom, which has a daily audience around a third that of Noted, but less than a fifth of the time on site.

The last twelve months

As I mentioned above, the last little while has been a trip. Facebook has been on a hard swing away from media, and no one has been immune. The election campaign this time last year provided an event-specific traffic windfall – The Spinoff had well over three million pageviews in September of last year, for example, an event we haven’t come close to matching since.

Yet if we compare an average of the May-July periods over the past two years, it’s clear that the algorithm jags have taken their toll. Both New Zealand’s biggest news sites are down on traffic and audience by roughly 10% over that time. Some of that might have been down to the pre-election rumbling, but the campaign had largely been uneventful until late-July. It shows, yet again, just how short-sighted the Commerce Commission decision to deny their merger was.

What does it all mean?

Basically, things are freaky out here. Facebook has turned from eager accomplice to surly acquaintance in what feels like the blink of an eye. In July 2017 social supplied 52% of The Spinoff’s web traffic; last month it was just 30%. So while our traffic and audience have increased year-on-year, it was a far more diverse and complex method of building an audience than before.

Despite the reprieve I talked about at the top, the Facebook chill is very much still here. Worse, it’s been here long enough now that we in the media (and, by extension, those interested in democracy and all that) need to understand Facebook’s capriciousness as the new normal. As… reality.

For media companies on the internet it demands an emphasis on loyalty and on brand – on creating an audience that either pays for your work directly, or reliably returns to consume it. It also demands the creation of alternate methods of distribution. You’ll notice that newsletters (like our excellent daily Bulletin) have come back into fashion, with Stuff launching a bunch lately. Suddenly we care about our apps again (ours is now free!). We’re all pushing our podcasts. And trying to squeeze more revenue out: hence the increasingly hard-to-avoid pop ups, pre-rolls and scrolling ads on the big sites. If you’re really paying attention, you’ll be able to sense a tension from newsrooms across the country as we all grapple with this new reality.

As a news consumer – if you’ve made it this far (apologies for the length, but it is complicated), what does it mean to you? It means that you need to take a bit more responsibility. Trusting social media to sort what’s good and important and bring it to your attention doesn’t wash any more. You need a another plan. The hierarchy of homepages is essentially broken, thanks to the crappy incentives baked into CPM. So you need a little discipline if you think knowing about this country matters. Signing up for emails seems a great solution. Subscribing or micro-paying works if you have the income and time to sustain it. Following your favourite journalists on social media helps for some.

But you probably need to do something different if you consume news digitally and want to keep doing it. Because Facebook has proven itself a distinctly unreliable companion, and many of us over here are shivering as a result.

A note on The Spinoff TV’s numbers

There’s another set of numbers which it would be remiss of me to ignore, even though explaining is losing and all that: The Spinoff TV debuted on Three in mid-June, to some extremely excellent numbers: the highest in the timeslot in ages. Then it basically halved over a couple of weeks. Knowing why is a fool’s game, but a combination of intuition and focus groups suggests that it might be because it was very much a work-in-progress in its first few episodes.

After four episodes it was moved an hour later, to 10.45pm, which is quite late. At which point, its ratings did what all shows do when they’re moved from 9.45pm to 10.45pm on a Friday – they tanked. This was extensively reported on by competing media, which is all in the game. (Four Mike’s Minutes is a lot though – maybe a record?)

Since then we have bounced around in low numbers, not disastrous, fairly normal for late on a Friday.

We know the show hasn’t been a smash on linear TV. Our forever antagonists The Taxpayer’s Union (to show just how excited they are about targeting a private organisation, check out exactly who they follow on Twitter) just put out yet another press release assailing the show, praising a National MP’s bill for greater accountability for NZ on Air under the admittedly pretty good headline “Spinoff TV Memorial Bill”. For what it’s worth, I would be heartily in favour of more metrics for publicly funded shows.

That is, so long as it’s all the relevant metrics: The Spinoff TV was pitched as an internet-first show, with a compile for TV on a Friday. That we would place the clips ad free online as soon as they were done, with more made than we could put on the TV.

The big idea was that we valued an online viewer as much as a TV viewer, and the proposal was adamant that a screen was a screen was a screen. The internet is the dominant media distribution channel for many under 40s, traditional media for most over 40s; yet the majority of government funding goes to shows that are first and foremost for linear television.

We wanted to try and break that, to try a different way to make a show. We’ve done that. And since we figured out what we were up to the online ratings have picked up:

We basically figured out what we were about around episode six. Since then every week it’s been getting better, and our views have picked up correspondingly. We don’t match the likes of Jono and Ben, obviously! But they’ve been going for about as many years as we have weeks.

The show isn’t for everyone. Even some of our biggest fans hate it! But it’s also picked up a bunch of people who really love it. Love that it’s fronted by two women, that it uses more than token te reo, that it uses talent who aren’t conventional TV performers, that it has more gay people, people of colour and young people on screen than we typically see elsewhere. That it intentionally breaks some of the formality and aesthetics of TV, again, exactly what we said we’d do in the pitch that got funded.

It’s also halfway through its first season. It’s about at Thursday on week two, if it were a daily current affairs show. So – honestly – we’re incredibly happy with its quality and its performance. It’s a real thing and its growing fast; and the focus on the linear ratings really doesn’t tell anything like the whole story.