Sam Brooks talks to internationally acclaimed opera singer Sandy Piques Eddy about the ins and outs of maintaining her voice, and how having a baby changed her career – in a way you wouldn’t expect.

Singing opera is like getting to the Olympics. Only the best of the best can do it professionally, once you get to that level you’re flown all around the world to do it, and there’s a four-hour opening ceremony (also known as an opera). And that’s before you get into the physical demands of actually singing it.

Beyond the clear artistry and technique that it takes to perform, often sans microphone to thousand-strong houses, I’ve always been curious about what it actually takes to maintain a career doing that.

The voice is an instrument, and just like any instrument, if you bang it against a wall one night and don’t take care of it, then it’s not going to sound as good when you take it out the next night. It’s simple cause and effect. Hell, even one cigarette after a few drinks can have you sounding like Tom Waits/Cookie Monster (choose applicable) driving a three-wheeled tractor down a gravel road the next day.

So what does someone whose entire career depends on vocal power, purity and artistry do to make sure their instrument stays in peak form? I could have, in theory, asked any singer or actor what it takes to maintain their voice. But why do that? Why not ask someone who is doing vocal Olympics all around the world?

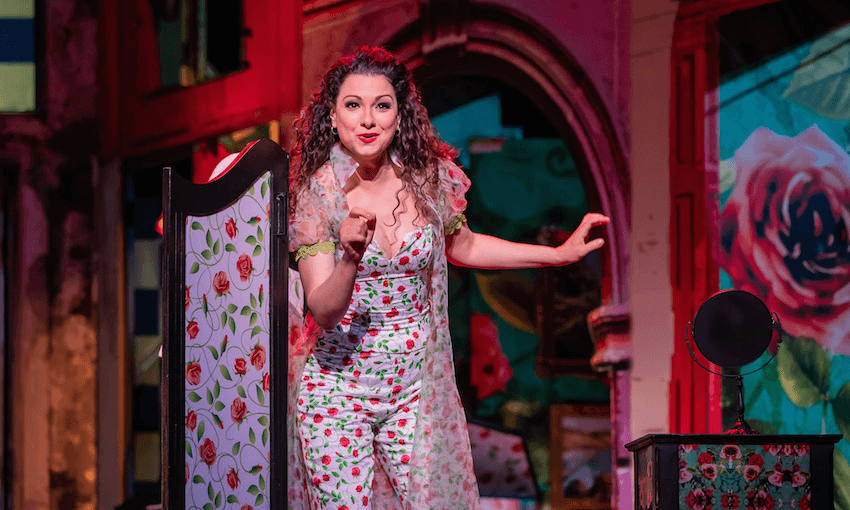

Enter Sandra Piques Eddy, who is about to perform Rosina in the New Zealand Opera’s production of The Barber of Seville. She’s performed in countless operas all around the world, including multiple critically acclaimed performances in the title role of Carmen in the USA, UK and Japan and, most interestingly, has heard her voice change from a soprano into a lyric mezzo-soprano register.

Who better to give me the lowdown on what it takes to maintain your voice, how your voice changes, and what the most dangerous thing to an opera singer’s voice actually is?

Let’s get straight into it: What does it actually take to keep your voice match fit?

A lot of people say that it’s like an athlete, and I can’t agree more, because this kind of singing, it reminds me a little bit of an Olympic sport, because there’s a lot of technical challenges. You have to be really on top of your game, so I’m getting up and I’m making sure that I’m doing exercises that are very fluid, but then also exercises for those quick coloratura fast notes. If I have to sing a note that’s this high then I try to go two or three notes above it. And then the same thing with the low notes.

So much of singing is physical, but it’s also about your range. It’s all in your head too! You’re like, “Oh, if I have these three notes above this high note then I’m good.”

I was talking to one of the singers here, and I said it’s funny that bel canto [literally ‘beautiful singing’], feels like I’m doing something very healthy and very good for myself, it’s like self-care – vocal self-care. Because you really do have to work on all the technical aspects of it, and you’ve got to do it so diligently outside of the practice room so then when you go to the rehearsal space you can make it look like it’s easy. I mean, that’s the goal, right?

The hope is that we make it look like we could do this anytime. It reminds me of figure skaters that do all these jumps. But we’re hoping that it makes it look super like, “Oh yeah, I could do this anytime.” It reminds me of figure skaters that do all these jumps.

They have to look like it’s effortless that they’re spinning in the air.

That’s exactly what this… this feels like Olympic sport singing. You know what I mean? It’s like fireworks. Vocal fireworks.

You’re just up in the air, vocally!

“Yeah, this? I could do this all day long.”

When it’s actually the hardest thing ever.

It’s like the salchows and the triple lutzes of singing, that’s what bel canto is. There’s a lot of trills and a lot of the extreme high notes down to the lower notes so it’s about trying to make it all look seamless. And it helps us singers, like if I went on to do a Mozart role after this, I would be very comfortable. If I went on to do Carmen after this, it would be very comfortable, because with bel canto you’re really exercising all of your range.

How do you protect your voice, when it’s your whole livelihood?

You know, the funny thing is, I think talking in loud spaces is possibly the worst thing you can do.

[I look around at this moment, making sure the space is quiet. Given that it’s just us talking in an empty conference room, we’re fine.]

Seriously?

After a show you’re excited, you’re in a big group, you’re having a glass of wine and trying to speak over everybody. So we just try to protect our voices in terms of drinking a lot of water, staying hydrated, getting enough rest, doing your vocal warmups before your singing, trying not to be around smokey places.

I think hydration’s the biggest thing though, honestly. And then trying to stay away from really loud spaces and having to speak loudly over the spaces. I always found that the speaking part was the most taxing, actually.

How so?

Because with the singing, it’s all actually supported with your breath, so we have to remember to do the same when we’re talking. I think that, thankfully, automatically, I start to support my speaking when I open my mouth. So my friends that don’t do it, they’re like, “You speak differently than I do.” And I’m like, “Oh, I do?”

If you do something in your head for twenty years you just start to pick up the techniques.

On that note, have you had a change in your over the 20 or so years that you’ve been singing?

Yeah, you develop.

And how do you deal with that?

It’s kind of like if you see yourself every day in the mirror you don’t really notice a change, but if you listen to your voice or you see pictures of yourself from ten years ago, you’re like, ‘I look different!’

It’s like looking at a stranger, some version of yourself from another time.

So when I listen to recordings from when I first started out, I had a lighter sound and a brighter sound. When I first started singing, during my undergraduate work at Boston Conservatory, I worked with kids. I was a choral director and a general music director, and I was singing soprano, so I was a higher voice type.

I taught for three years; sixth, seventh, and eighth graders, so 12, 13, 14 years old. So we had a lot of sopranos, a lot of altos and we had a group where it was only 12 baritones. So I would find myself singing with the boys. And then it was very easy for me to sing down in the lower register.

When I went back for my master’s degree a few years later, I went to a wonderful teacher named Susan Ormont and she said, “You’re either a soprano that is a middle-voice soprano, or you’re a mezzo-soprano.”

And it’s funny, because you, as a soprano, you sing the sweet young girl roles, and then as a lyric mezzo, when I was starting out, I was playing all the boy roles. We were doing Marriage of Figaro – I played the page boy – but even still now last summer I sang Orfeo in the Gluck Orfeo ed Euridice, the Greek myth.

I started off as really, like a soprano, a lighter, brighter voice. And then I went as the mezzo-soprano, and then I started singing this kind of repertoire, and I’m very happy that I’m still singing it. Carmen started to happen because my voice started to get richer after I had my daughter.

Really? How does that change your voice?!

Maybe I’m delusional but I think it’s for the better. I didn’t know I was pregnant at the time, but my voice teacher at the time went, “What’s going on?” She could hear something but no one else could hear it.

Afterwards, I found myself very grounded, vocally, just secure and grounded. And also I think I was just so happy, honestly, so much has to do with your mind set, and I was just so happy with this new chapter in my life, as cheesy as that sounds. I was just so happy to get the opportunity to be a mom. And after that, it was funny, the year after that it just seemed like everything just picked up.

And I don’t know if it was… you don’t know what, the chicken or the egg, but people that’ve heard me in the last five or six years they’re like, “Your voice seems like it’s gotten bigger.”

Everybody’s voice changes. So you just go with it. You have to always kind of listen with an objective ear and you have to get people on your team. I always say I have a good team, because I have a great teacher and I have great coaches, and people that I ask, “Please tell me the truth and let’s focus on this.”

And I feel like I never stop learning.

The Barber of Seville opens at the ASB Theatre in Auckland on June 6, and tours around the country until August. You can find tickets right here.