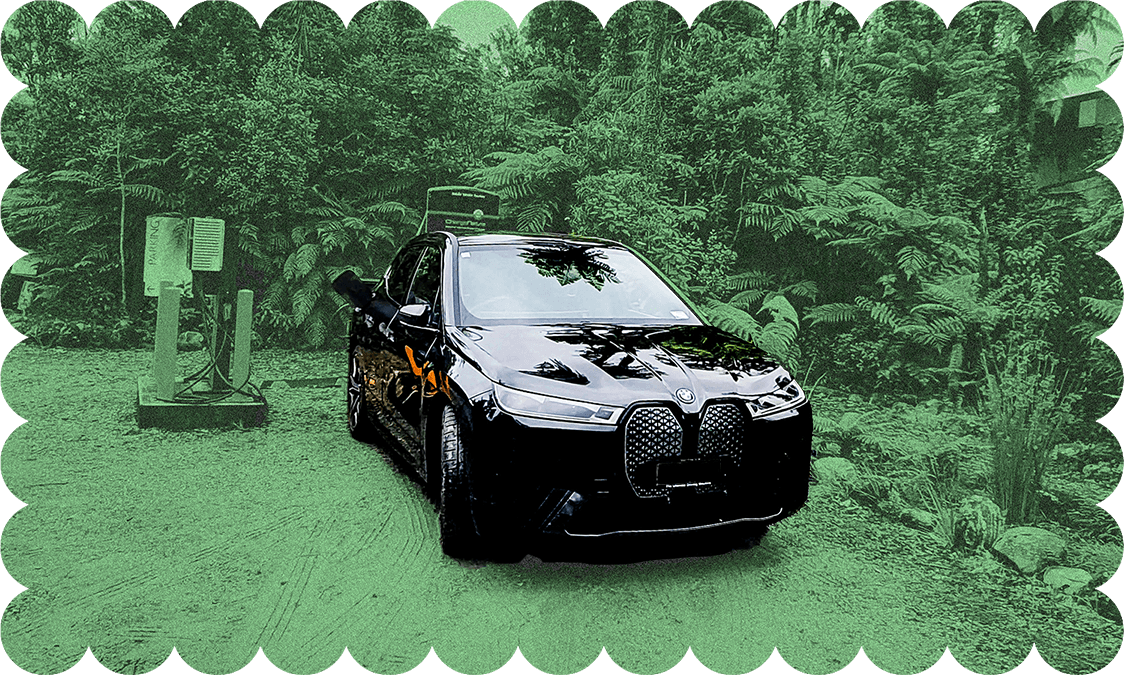

In the first part of a brand new series, Don Rowe dives into the infrastructure putting the Aotearoa EV revolution in motion.

Talk to almost any electric vehicle neophyte and they’ll probably start with two questions: where do I charge them, and how far can they go?

At the end of 2016 there were just 20 commercial electric vehicle charging stations in New Zealand. Today, six years later, that number is closer to 300 public rapid chargers across both islands, with many more likely installed on public and private properties. That 1500% increase was seeded in large part by a 2016 partnership between ChargeNet and BMW, announced by then minister of transport Simon Bridges who said charging infrastructure was a “vital part of the ecosystem” necessary to make electric vehicles a success.

The ChargeNow partnership saw the two companies install more than 100 direct current stations around Aotearoa, with a view towards creating an “Electric Highway” spanning the country and unlocking long-distance travel for EV drivers. Since then ChargeNet has installed hundred of additional fast charging points with the support of New Zealand Government’s Low Emission Vehicles Contestable Fund administered by the Energy Efficiency & Conservation Authority.

Karol Abrasowicz-Madej, managing director of BMW Group New Zealand, says BMW saw the same chicken-and-egg problem of charging infrastructure and EV uptake. But in a country with 80% renewable energy on the grid, the problem also created an opportunity.

“Entrepreneurship is a part of our DNA and a part of that is futuristic thinking. If we believe that the future of mobility will change, we need to think like our customers,” says Abrasowicz-Madej. “We need to ask ourselves ‘what will the customer need in order to consider a purchase of the vehicle that we provide?’ The first thing that comes to mind is charging infrastructure. We might have a fantastic product but if there is no chance to charge them up…you can’t drive them. That’s why we partnered with ChargeNet on the rollout of their network.”

—

This story from the Electric Highway is brought to you by BMW i, pioneering the new era of electric vehicles. Keep an eye out for new chapters in Don’s journey each week, and to learn more about the style, power and sustainability of the all-electric BMW i model range, visit bmw.co.nz.

—

Charging infrastructure is one of two key psychological pain-points facing potential customers, says Abrasowicz-Madej, the other being range anxiety. And so, as the ChargeNet network grew BMW introduced the i3, one of only two fully electric vehicles available to buy firsthand on the market at the time. In 2015 it was awarded the AA New Zealand Car of the Year award.

“We knew that bringing a pioneering vehicle onto the road would help our customers to adapt to a new market. This is a car that perfectly fits areas like Auckland. We were confident that the distances the car would cover are enough for the daily commute – an average New Zealander drives 22km a day, maybe 40km in Auckland if someone is living outside of the CBD.”

The success of the i3 encouraged BMW to continue to grow their range of electrified vehicles, attracting customers through what Abrasowicz-Madej calls ‘the power of choice’ – give the customer options, and they will come. New Zealand lifestyles often demand more than a hatchback runabout, so models like BMW’s X3, a full size SUV, were electrified, offering hybrid models alongside traditional internal combustion engines. And now, with the release of the iX, BMW has brought a fully electric SUV to market.

But in order to provide the choice of larger vehicles, with longer ranges, the network needed to expand.

Today, following six years of investment from ChargeNet and its partners, electric vehicle charging stations are near ubiquitous; from Kaitaia to Kaikoura, Turangi to Tekapo – even halfway up Arthur’s Pass – the softly humming towers can be found. Along New Zealand’s state highways, a charger is available roughly once every 75km. And most chargers are placed strategically near cafes, supermarkets and attractions like the National Army Museum in Waiouru, removing another pain-point: boredom.

Unlike automakers like Tesla, whose charging stations are hard-locked to their vehicles, the ChargeNet chargers on the Electric Highway are available to all. The availability of hundreds of chargers across New Zealand has helped power a historic growth period in the electric vehicle market, which has doubled annually from 2016 to 2019. Today, there are around 38,000 EVs on New Zealand roads, up from 25,000 this time last year – and significantly more than the 5000 registered in 2020. The Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority predicts that number to grow to up to 165,000 vehicles by the end of 2023.

“Putting in the chargers means that already at the time of purchasing the vehicle, it is not only convenient for our customers but it is future-oriented,” says Abrasowicz-Madej. “We are working towards customer satisfaction, not building barriers to create stickiness to a charger. Instead we created stickiness to a product.

“Customer satisfaction comes from the use of the product. We want them to charge wherever, whenever, and we want them to stay mobile in the premium environment we have designed for them.”

But, says Abrasowicz-Madej, there is no premium experience without sustainability. BMW breaks sustainability down into three areas, he says: governance, social responsibility and environmental responsibility. BMW considers where the car is produced, who is working in the factories, and where the energy is coming from that powers the plants – in their case the majority of energy is generated through wind and solar panels.

“We also look at the sourcing of cobalt and lithium which we believe should come from extremely controlled and clean sources, which we buy through our own systems from Australia and Morocco then deliver to manufacturers. We look at the use of raw materials in order to avoid the deterioration of the climate, and secure our aluminium from suppliers who produce it using green energy. We use things like fishing nets for the production of floor mats.”

And although transport accounts for around 20% of New Zealand’s carbon emissions, a shift to electric vehicles alone will not solve the problem of emissions globally – electrifying every light vehicle in New Zealand would increase electricity demands by around 20%. And so electrification is only one part of a wider move towards sustainability which must encompass the entire supply chain, says Abrasowicz-Madej.

“We look at every single element and try to reduce the CO2. That is why we have the goal of 80/40/20, which is an 80% reduction of CO2 emissions in the supply and production chain, a 40% reduction on the unit emissions per car, and a 20% reduction in the end phase.”

Reducing emissions will take the intervention of governments, investors, automotive manufacturers like BMW as well as the public at large. A key step is the accelerating shift to zero emission vehicles spurred by the increasingly ubiquitous Electric Highway, but progress remains a collective effort. No one party can drive change alone.