Off-peak electricity is often greener and more affordable due to lower demand. A new Green Meter by Electric Kiwi shows consumers just how green their power is.

By now, most of us know the drill. Faced with the double-whammy of chilly winter temperatures and a skyrocketing cost of living, we’re eking out extra savings on our power bills by moving our electricity usage to times of day when prices are lower. If you’ve ever set yourself a mid-evening reminder to start the washing machine, run a bath, or plug in the EV, you’re among the hundreds of thousands of Kiwis regularly “load shifting” to take advantage of cheaper off-peak electricity on a time-of-use plan.

It’s fairly widely understood that when there’s a lot of demand on the electricity grid – at breakfast time, for example, or when people are getting home from work – electricity is more expensive to generate. But fewer of us realise that the CO2 emissions of our electricity supply are also subject to peaks and troughs. That’s why Electric Kiwi built the Green Meter, a tool that helps consumers understand the predicted “greenness” of their electricity usage at any given time.

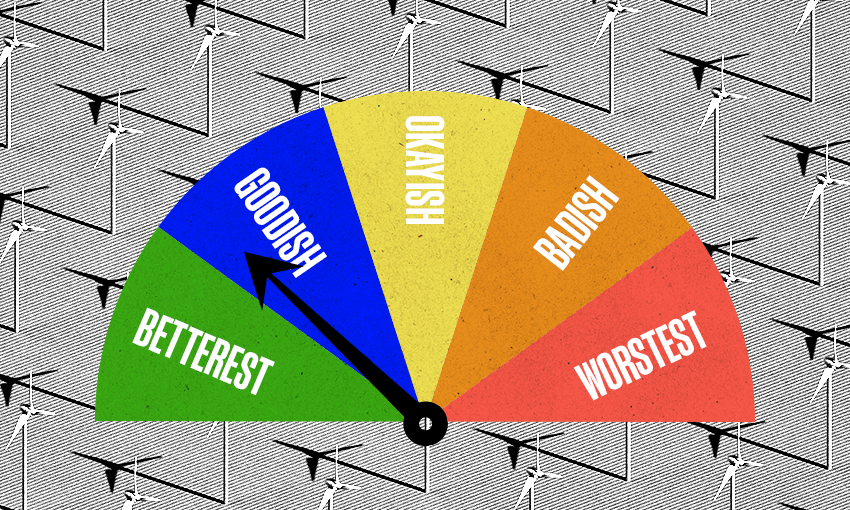

Using recent emissions data, the Green Meter produces a constantly updated CO2 forecast for the Aotearoa electricity grid. Carbon emissions are ranked from “Betterest” (less than 50 tonnes of CO2/half hour) to “Worstest” (a scary 400+ tonnes of CO2 produced every half hour), with “Goodish” and “Okayish” somewhere in the middle. There’s also a Carbon Insights graph showing actual average emissions for the last few months, plus forecast data for the next few days. Just like with a weather report, the short-term forecast is very accurate; the longer range one a little less so.

Peak carbon emissions often happen in tandem with peak demand on the grid. On a cold winter’s night, when most people are at home with the heating on, our renewable electricity sources (hydro, geothermal and wind) are less able to keep up with demand, and fossil fuel generation (e.g. coal) has to be called into service. But that’s far from the full story, according to Andy Cooper, Electric Kiwi’s chief customer officer. There’s also the supply side to think about. “Cold nights tend not to be a very good time for wind or solar energy” he says, “and while the lakes are full at the moment, when our water levels are low that’s also a worse time for carbon emissions.” Higher than usual emissions from electricity generation can be an issue in both summer and winter, and at any time of the day.

As the country moves into its electrified future, concepts like load shifting and emissions monitoring are only going to become more important. The electric vehicle revolution is an unprecedented opportunity to “swap dirty, imported fuels for clean, homemade ones”, Cooper says. But the electrification of our vehicle fleet is also going to put a huge strain on the national grid, and the sooner the potential impacts are put on people’s radars, the better. “We need financial incentives, we need good information and we definitely need some clever technology to help consumers do load shifting at scale,” he says. “Because the cost of not doing that is that our networks probably won’t cope and our costs will skyrocket.”

Creating a Green Meter is part of the effort to get consumers thinking about the carbon footprint of their electricity usage, and how small adjustments can make a big difference. Given that New Zealand’s energy supply is already predominantly renewable, load shifting is by far the best thing you can do to lower your electricity emissions further, Cooper says. He’s concerned that power companies selling “green certified” electricity are confusing the issue. “We’ve potentially got the most engaged customers in the country thinking that they should change power companies rather than change behaviour – in my opinion those companies need to have a good hard look at themselves.”

The Green Meter is also laying the groundwork for an electricity innovation that hasn’t had as much attention as EVs, but could prove just as impactful. Within the next year or two, with the help of smart home technology, electricity suppliers like Electric Kiwi will be able to manage the supply of electricity to customers’ homes, allowing water heaters, EVs and other electricity-hungry devices to be charged at the lowest possible price and with the least impact on the climate. It’ll all be automated on the customer’s behalf. “I think ultimately that always proves to be the most successful option,” says Cooper. “The less people need to do, the better.”

And that’s where the Green Meter comes in. “We want more and more people to think about this stuff so that, as those automations come along, they’ll understand what’s going on and be ready to take part in those new propositions that make life easier, make things cheaper and help us meet our climate goals. So it’s a bit of a win-win.”

Because it’s a forecast of the entire electrical grid’s emissions, the Green Meter is relevant to every electricity consumer, whether they’re an Electric Kiwi customer or not. Why not wall it off? “I think when you’re in an industry like ours, you have a pretty big social responsibility to do the right thing for the country, rather than yourself,” says Cooper, who’s quick to admit that encouraging load shifting makes good business sense too. Anything that flattens electricity demand now helps reduce the need for expensive new electricity generation infrastructure in the future.

If you’re on a time-of-use electricity plan, you already know the financial benefits of shifting your power use to times of day when demand is lower, and when fossil fuel-powered generation is likely lower too. But load shifting is about a lot more than just the effect on your back pocket – it’s also better for the environment, and for the health of the electricity grid as a whole. When you put it like that, having your bath an hour later seems a small price to pay.