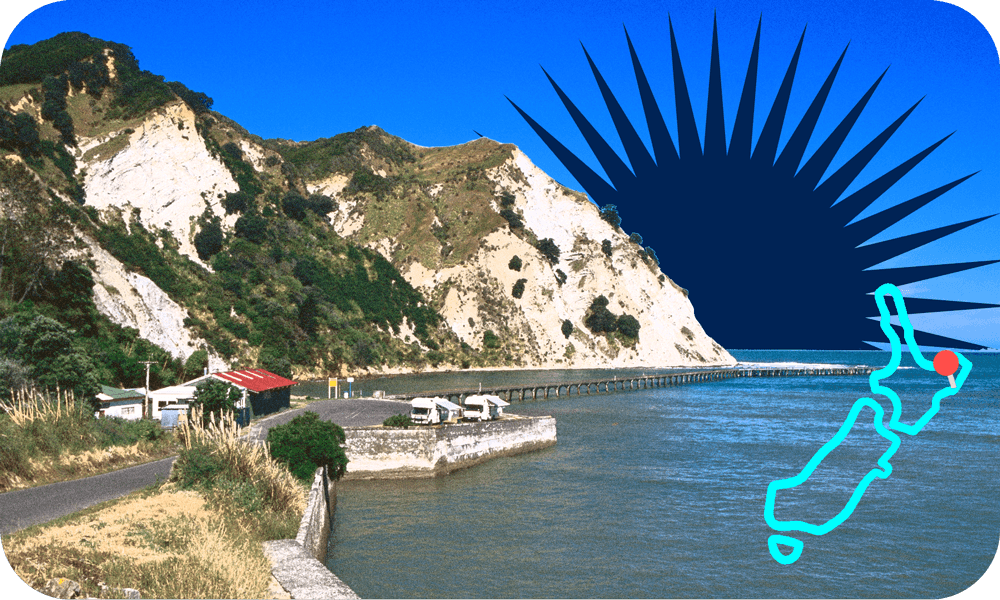

In this story from the Electric Highway, Don Rowe learns how residents and organisations in Tāirawhiti are dealing with the first-hand effects of a changing climate.

The locals in Tairāwhiti are getting used to extreme weather events. During the flooding in March, Zak Horomia, chairman of the Hinemaurea Marae, told me 100 year storms are turning into annual events. In one six-hour period, Te Puia had almost 240mm of rainfall. The broader region experienced more than three times the expected monthly rainfall in a single day.

Diluted sewage flowed through the awa as the Gisborne District Council was forced to open emergency valves to release the intense pressure. Urupā narrowly avoided being inundated by the torrential rain. Bridges were washed out and roads shut, with the only access to some areas by inflatable rubber boats. And the most heavily affected were those living rurally, who often have unique health needs and are vulnerable to being cut off from medication and treatment.

The flooding in March came just four months after the previous storm in November when residents were evacuated from settlements like Mangatuna. Academics and locals agree – the increasing severity of storms is being driven by climate change. In places like Ruatoria, droughts and northwesterly winds drive dust from the Waiapu awa through town, soiling washing and vehicles.

But June and July are also the rainy season on the coast. When my roadtrip in the BMW iX took me to Tairāwhiti, I found a region still working to repair the damage from the last big weather event. And with winter approaching, I wanted to know what was being done to prepare for what might come next.

—

This story from the Electric Highway is brought to you by BMW i, pioneering the new era of electric vehicles. Keep an eye out for new chapters in Don’s journey each week, and to learn more about the style, power and sustainability of the all-electric BMW i model range, visit bmw.co.nz or click here.

—

With the March clean-up expected to take anywhere from 18 to 24 months, up to $500,000 was made available from Work and Income’s Enhanced Taskforce Green scheme, helping local jobseekers find mahi restoring their communities. Another $175,000 came from the Mayoral Relief Fund as well as an additional $150,000 earmarked specifically for the region’s farmers and growers, but the total cost is expected to reach into the millions.

Tairāwhiti Civil Defence Manager Ben Green says that the effects of weather events on critical infrastructure mean TCD response operations can be hamstrung by closed roads and damaged bridges.

“The impact on roading networks means patients can’t access medications or specialist care. Power outages impact those who are reliant on medical equipment, for example dialysis machines which mean they either have to relocate or back up power options like generators are provided.”

The Tairāwhiti Emergency Management group has identified the region’s ageing, declining population and increasing income inequality as risk factors in the event of natural disasters. Land clearance from pastoral farming since the 1880s has accelerated soil erosion and large increases in coastal flooding is expected as a result of climate change-induced sea level rise, affecting surface and stormwater drainage.

Around 90% of landslides in New Zealand are caused by rainfall which is expected to increase alongside greater frequency of droughts as the climate worsens, posing threats to the few roads in and out of settlements in the area. Up to 85% of people in the region say they can survive on their own for three days, says Tairāwhiti Civil Defence, but mental distress following emergencies remains a concern.

“There are [mental health concerns] on a number of levels – livelihoods are at risk, for example forest operations can’t operate due to roads out,” says Tairāwhiti Civil Defence Manager Ben Green. “There have been back-to-back events and resilience is tested with many having suffered extensive damage or impact on their lives. Then there is dealing with the process post-event; people deal with the stress of navigating insurance – or no insurance – upheaval, and recovery.”

Some marae like Hinemaurea have installed their own floodgates, averting the worst of the latest weather events. Others are still vulnerable, particularly those situated around awa or near sea level. Community outreach remains a challenge, with some whānau unwilling or unable to evacuate at a moment’s notice. Last year, following a 7.1 earthquake off the east coast, kaumātua like Horomia coaxed residents out of their homes to safer ground.

The stunning isolation of Tairāwhiti – the air of timelessness, of an Aotearoa gone by, where homekill isn’t just a marketing term – is what draws countless tourists into the rohe. It remains one of the last hubs of New Zealand Gothic, where the main street is silent but for the clop-clop of horse hooves and the shaky treble of a radio playing through an open window. But that same distance, that same insulation from outside forces, can become a logistical nightmare when the storms roll in.

In the past, critical supplies have been flown by helicopter into isolated settlements in the area. But locals living rurally historically suffer worse outcomes broadly, and face unique challenges in times of natural disaster. While the rubber boats seen in March’s storms were a volunteer effort from a local surf lifesaving club, extreme measures like air support are only possible, says Green, if the weather is conducive.

“Beyond that there are no other options, so the community messaging is to have supplies in preparation of being cut off.”

Major steps are being taken to try and improve the region’s preparedness. Green mentions a new emergency coordination centre and bespoke new flood modelling systems – the latter being created using a combination of Niwa and regional council data – which should allow for more effective proactive and responsive care. Civil Defence are also undertaking an extensive community education and training programme, as well as the provisioning of 20 emergency pods containing communication equipment, shelter and kai for isolated marae and communities around the region.

Green, like many from the region, knows that these events will keep coming – at the time of publishing, another severe weather warning had just been issued for Tairāwhiti. But the whenua, and the people, are resilient. And when the waters recede, as they always do, Tairāwhiti will retain its warmth, its mana and its beauty. The hope for those who call the region home is that they’re given the support to ensure those qualities can be retained not for decades, but for generations to come.