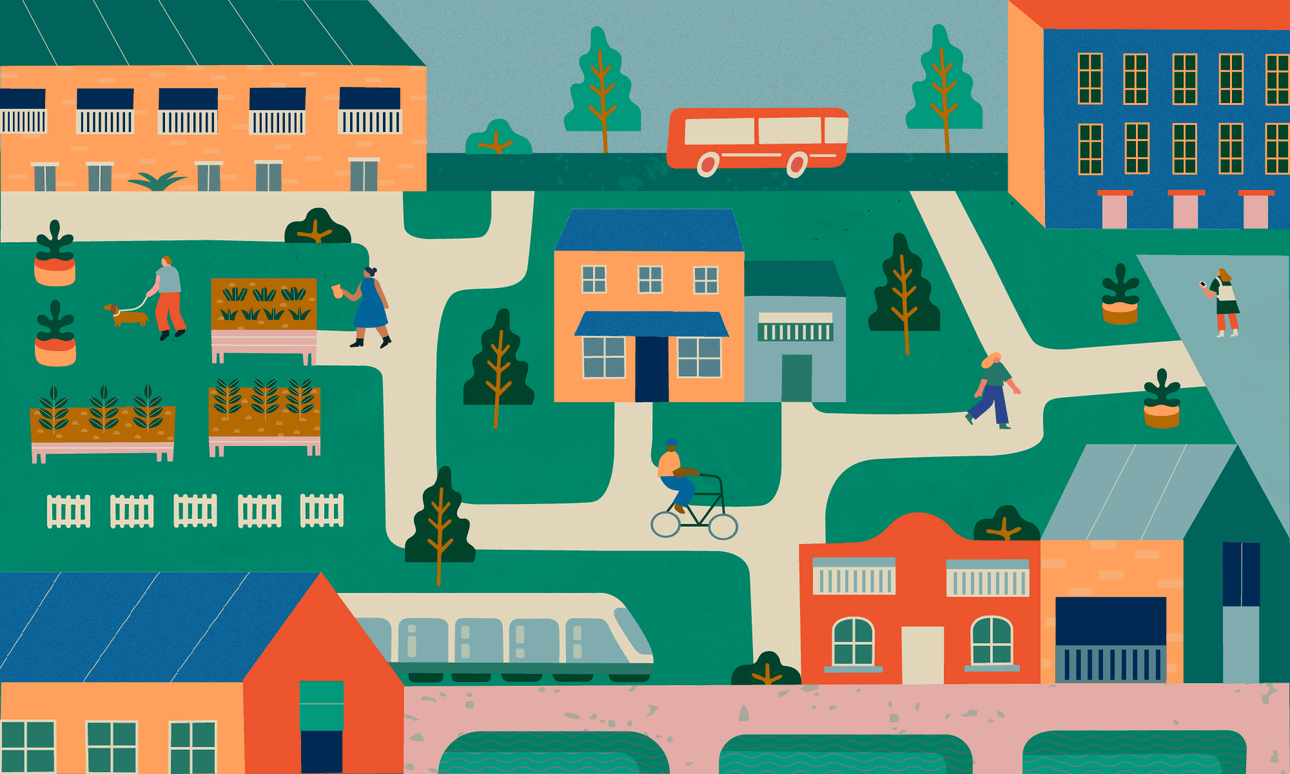

At the heart of many of New Zealand’s major transport and infrastructure projects is a vision of a sustainable, affordable, safe and diverse future. What will it take to realise this vision?

From Auckland’s ongoing City Rail Link to plans for linked-up rapid transit networks, major transport projects are capable of transforming the communities they will service. The trajectory of New Zealand’s future relies on these metamorphic projects, which aim to provide catalytic networks that change how people experience, live and move around their cities, towns and regions.

Large scale projects generate a spin-off of small-scale projects, which also have a significant impact on enhancing communities’ connections with the spaces they inhabit. As Christchurch began to rebuild after the earthquakes over a decade ago, social enterprise Gap Filler was born out of wide-spread dormant spaces to inspire a city whose vibrant CBD had been suddenly decimated. Initiatives like the “Dance-o-mat” – a coin-operated washing machine powering speakers over an open-air dance floor – reactivated places and gave new life to the rubble which had become so much of the Christchurch cityscape.

These macro and micro projects work hand-in-hand to connect communities and neighbourhoods, enhancing places and spaces by encouraging activity, engagement and a sense of ownership and pride.

So how can we ensure New Zealand’s infrastructure is built to meet the demands of the future? How do we get public buy-in on projects that might have some teething issues? And how do we advance our infrastructure while recognising the importance of its history?

The term “placemaking” is a response to these questions; a framework centred on creating spaces where people want to work, play and live. It’s a holistic approach to landscape, community and infrastructure design that celebrates the connections between people, the natural and built environment and strengthens both immediate and long-term wellbeing.

Alan Whiteley, head of landscape architecture and urban design at WSP New Zealand, says one of the most important principles of placemaking is engagement between developers, mana whenua and the community they’re seeking to operate in. “When everything is done, if they can see their faces in their places they feel ownership, and that ownership creates stewardship,” Whiteley says.

For those countries that are high on the happiness index – often Scandinavian countries – one of the common factors is that citizens feel like their government has their best interests at heart, and that it’ll work with them to co-design outcomes.

Co-development and stewardship is an important part of the longevity of a project – when the community is behind something, we can work together to protect, grow and nurture it, says Whiteley. “That meaning and connection to a place essentially creates identity and happiness for communities and encourages people to connect together socially; and helps them to have more frequent interactions with others, with nature and the landscape, and participate in the vibrancy of their public realm.”

The story of Aotearoa has a whakapapa of “place” that is embedded in our landscapes, histories and our cultures. WSP principal urban designer Haley Hooper says understanding and expressing Aotearoa’s indigenous culture and place in the Pacific is crucial when it comes to growing the futures of our environments, ecosystems, cities and towns.

“We’re looking to create places that really evoke a sense of community for people, from what they’ve been for many years before, all the way through to what they could be in the future,” says Hooper. “There is a generosity, sensitivity and richness in collaboration – which reveals poetic and unique aspects of sites that you just can’t get from flat technical evaluation.”

Creating a shared vision that is founded on these elements informs design that is responsive and reflective as well as functional, distinctive and expressive. The importance of those aspects, like the layered cultural importance of sites, informs how people relate to the place and how successful the project has been alongside the interests and priorities of the people. Nurturing and working sensitively with the history, and existing situations and contexts of places also ensures a balance is established between now and what is proposed – one which integrates current peoples and place so that communities are supported and don’t get driven out when changes do inevitably come.

One of the most cited international examples of what can happen when urban design doesn’t take into account the communities it’s impacting is the New York City High Line – a city garden and walkway built on over 2km of unused raised rail line through Manhattan’s west side. Since it opened in 2009, millions of locals and millions more tourists have visited the High Line to take advantage of the unique perspective it gives on the Hudson River and the west of the city.

But the real outcome of this huge influx of foot traffic is a soaring demand for property and development (and a commensurate steep increase in the cost of living) in an area of Manhattan which was previously a “mix of working-class residents and light-industrial businesses,” according to the New York Times.

Approaching all of these major infrastructure projects as parts of a wider ecosystem, where each area has its own history, character, needs and challenges, will ensure that when the city does become more interconnected by things like public transport and housing density, the unique cultures of individual communities aren’t homogenised, but their diversity is celebrated and integrated into the changes to make better outcomes that are more representative of all.

New Zealand has one of the highest car ownership rates in the world, with 818 vehicles per 1,000 people, according to 2019 Ministry of Transport data. Frederik Cornu, market leader for sustainable places at WSP says that when he moved to New Zealand in 2019 after working in Europe and Asia, he couldn’t believe the amount of above-ground parking buildings here.

“Most of these multi storey car parks have been built over the last 50 years. I don’t know any other country like that – the number of high-rise carpark buildings here is mindblowing, notably in the centre of cities.”

That reliance on cars is a symptom of the government’s decision back in the 1950s to lean into the “freedom” of car ownership – building motorways and investing in roading projects while also taking away many of the public transport options in our major centres.

“New Zealand used to have a very good public transport system less than a century ago – and very high patronage actually – so we know it’s possible. This is where we need education at all levels, for people to realise that there is another way to live than having to take your car everywhere,” says Cornu.

Ultimately, promoting a change from the “quarter-acre dream” so prominent in New Zealand to a more accessible, denser and safer “four-kilometre block” is the challenge that city planners and developers now have in our main centres.

“We’ve been used to this very expansive way of living and we maybe haven’t yet come to a place where we can also look at what the advantages and the different values of being in closer spaces and having much greater amenity at your reach are,” says Hooper.

To get to that stage, she says, we need strong and critical decision-making by central and local governments and developers, alongside a population empowered to participate in creating the visions for their community’s future.

“We need to be bold – bolder than we are – to make purposeful changes that lead our country through into ways of working that reflect who we are and how we can live in Aotearoa. And we have to also keep pushing to step outside and question what has been known as New Zealand’s ‘business as usual’. We need to take the ingenuity that’s inherent in our culture, and really lean into how we work in our cities; our communities; our places.”