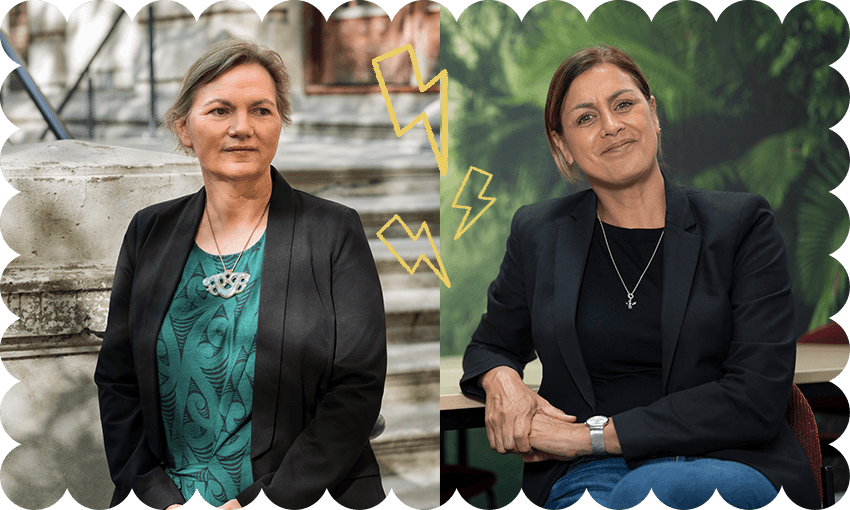

In December the University of Otago appointed its first wahine Māori dean, then just months later appointed its second. We asked professors Suzanne Pitama and Joanne Baxter what this means for them, the university and Aotearoa.

When it was published in 2019, the study Why Isn’t My Professor Māori? revealed Māori made up just 5% of New Zealand’s total academic workforce between 2012 and 2017. And that number was not increasing. The research criticised the universities’ diversity policies for having little impact on representation, and questioned their desire to build “sustainable Māori academic workforce” and their level of commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. And the lack of Māori academic staff has meant mātauranga Māori has struggled to find its way into course syllabus.

Perhaps that’s why, when two dean roles became vacant last year, Professors Jo Baxter and Suzanne Pitama weren’t initially going to apply – despite their qualifications. Between them, the pair has over 40 years of academic experience in many roles within Māori health academia, and both are well-known figures in medical circles for their staunch advocacy for Māori equity in health, public health and patient outcomes.

When Pitama was appointed to the role of dean and head of campus for the University of Otago’s Christchurch campus in December 2021, she became the first wahine Māori dean of any Otago medical school. She says she was encouraged to apply by colleagues who had seen her leadership skills develop since she started as a lecturer at Otago in 2001.

“I had not actually seen myself in that position. I didn’t visualise that that was my future,” she says. “It was peers saying, ‘you should go for it, this is something you should do’. In a big institution where there’s not a lot of Māori it’s quite overwhelming to have so much non-Māori support.”

Another landmark came months later when Baxter, a public health medicine specialist, was announced as dean of the Dunedin School of Medicine in February. Baxter says it was also that peer support that encouraged her to apply for the job.

“I was approached by a range of staff from the medical school telling me that they would strongly support my application and it felt like I was heading into safe territory. And that the people who I would be leading were keen for me in the role,” she says.

They’ve both previously held roles as associate dean Māori at their respective schools, and Baxter and Pitama are experienced in Māori leadership in Māori-specific spaces. Now they want to see that leadership and mātauranga Māori translate into roles with wider scopes.

“This is the first time in some time, my role has not been a Māori specific one,” says Baxter. “I think the timing is really good for having wide leadership expertise, including skills in how to implement pro-equity, pro-Treaty, anti-racist strategies, goals and objectives.”

She says those strategies that were ingrained into her work as associate dean Māori – upholding tikanga, manaakitanga, kaitiakitanga, equity – are just as important in her new role. She believes those qualities are essential to any person involved in remedying inequity in Aotearoa.

“It’s about figuring out what leadership looks like in this space. I happen to be Māori and have this expertise, but I think all leaders now ought to be able to lead equity, Treaty, anti-racism, and cultural safety.”

Pitama agrees – that kaupapa hasn’t changed between her role as associate dean Māori and her new role as dean of the Christchurch campus. Now, the experience she has working to improve Māori health outcomes is being applied across the whole medical school.

“What I’m hoping is the equity and social justice approach that Jo and I have used consistently our whole academic careers will help transform and make the medical school more inclusive, more diverse and more supportive of equitable opportunities for all our staff and students, as well as patient outcomes,” says Pitama.

Their appointments signal a gradual shift in the leadership styles that are valued in our universities, and wider society. They believe their appointments are a commitment from the University of Otago that tikanga and mātauranga Māori are recognised and respected.

“It’s one of the oldest universities in the country, but it wants to be at the forefront of creating change. Otherwise, I just don’t think it would have employed us, we’re way too sparky,” says Pitama. “If you wanted to keep the status-quo, you wouldn’t have put us in these positions.”

After years of being a very vocal figure at the university, Pitama had come to believe she wouldn’t be appointed to a prestigious role, especially one where she had more of a platform than ever. She thinks her promotion signposts the direction of change for the university towards a more equitable agenda, grounded in social justice.

“They knew what they were getting when they appointed us. We have not been quiet on the sides over the last 20 years that we’ve worked at the universities,” she says.

That shift has been gaining momentum across the country. In 2021, Khylee Quince was made dean of law at AUT, becoming New Zealand’s first Māori dean of law. But these appointments are about more than just opportunities for these individual women, says Baxter. She wants other young Māori and women to see them leading from the top.

“It’s super important for our communities and our young people to see us in these roles. And, to me, it’s a bit of a shocker that there’s been so few Māori in these leadership roles, but it’s also a bit of a shocker that there’s so few women.”

Pitama and Baxter want to use their positions to build a culturally competent health workforce, for Māori, for women, and for anyone who has been less represented in medicine in New Zealand. Baxter says leading the school is an opportunity to create a safe environment for students, colleagues, and patient outcomes to thrive.

“One of the things I think we bring is an optimism that things can be different, and that we need to persist, we need to draw on strengths. Then, how do we create space, so that the strengths of the young people that come through can be drawn out, so they can work to solve some of the equity challenges that we face?”

Eru Pomare, who became the first Māori dean of a medical school when he was appointed head of Wellington Medical School in 1993, has inspired both women and helped them understand what they could achieve. But they want to ensure that it doesn’t take 20 years before the next Māori deans are appointed.

“I’m hoping the legacy that Jo and I leave behind is that it becomes usual to have Māori in leadership within our medical school,” says Pitama.