In an interview to launch the new podcast series Venus Envy, the prime minister calls for more ‘conversations around consent and healthy relationships’ in the wake of the global outrage sparked by the Harvey Weinstein revelations.

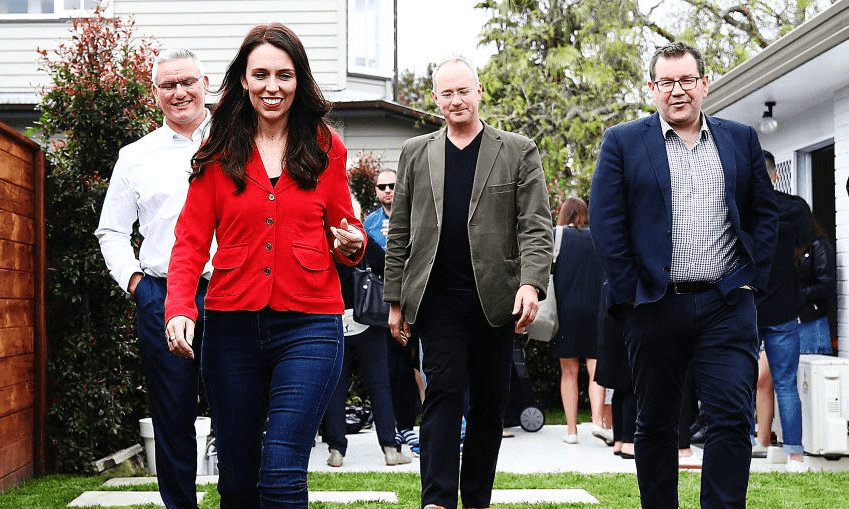

The New Zealand prime minister has called for the energy of the #MeToo movement to be translated into action. Speaking to the Spinoff as part of a new podcast series in collaboration with the Auckland Museum, Jacinda Ardern said that the sharing of stories risk equating “to nothing in real terms” if there is no resulting change.

“What we need to do is then say, OK, well what next?” Ardern told Noelle McCarthy in the first of the podcast series Venus Envy. “You don’t want a movement, really, of women continually feeling like they need to tell stories that then equate to nothing in real terms. And so that’s the question that I’m interested in asking: what next?”

The challenge was to change the view around what was acceptable behaviour, she said. “That to me comes back to that respect question, of how we treat one another, of conversations around consent and healthy relationships.” These were “things we should be talking about in our schools, in safe places, where we learn and kind of our social norms, before people are entering into the workplace”.

Her remarks come in the first podcast in the Venus Envy series, which forms part of Are We There Yet? Women and Equality in Aotearoa, an exhibition at the Auckland Museum focused on “celebrating the historic anniversary of suffrage in Aotearoa, while also looking at the successes and speed-bumps of gender equality in New Zealand”.

The Venus Envy podcast: Download (right click to save), have a listen below, subscribe through iTunes (RSS feed) or read on for a transcription of the conversation with PM Jacinda Ardern in full.

The solutions to the issues raised in recent months needed to have both a cultural and policy dimension, she said. “When you’ve got a country where you have such high rates of violence against women, you want to remove every barrier so a woman can make a choice, have a choice about her future. And, so long as we have women over-represented in low-paid work, or unsupported as carers, the choice is removed.”

The wave of #MeToo stories had prompted women to revisit the ways they’d faced similar abuses in their own lives, said Ardern. “You’d be hard-pressed to find a woman who hasn’t had an experience that they look back on now and think you know that fell into that category, and then start to do the assessment of why did I not say anything, how did it make me feel, what stood in my way of really questioning that behaviour?”

Of her own encounter with harassment, the details of which she declined to specify, Ardern said: “Relative to some of the experiences I see women sharing, which are devastating to read about, mine was minor in comparison, but at least it gives me that insight that probably other women have of when there’s a power imbalance and you have those experiences it does make it quite difficult … Every workplace will have someone with a story, and we cannot simply think that it’s particular industries that are affected.”

Speaking before the birth of her child, Neve, the prime minister emphasised the role men had to play in redressing the inequalities that had been laid bare by the #MeToo revelations. “I’m a pragmatist as well, so when I talk about feminism I talk about equality, my view is, you know, men not only can be feminists, they should be feminists, and if they feel if they believe in basic principles of equality, then they need to get on board and start rowing as well.”

Ardern also addressed her role in the Women’s March, the global demonstrations which followed the election of Donald Trump to the American presidency in 2016.

“I spoke that day about those issues, of violence and financial security because I will always stand in solidarity with women globally, particularly around issues of maternal health and wellbeing, but we can never forget we need to get our own house in order, too,” she said.

The prime minister said that the relative rarity of a woman as head of government only really hit home on the international stage. “When I go overseas it does become more obvious to me.”

At the Commonwealth leaders meeting in London recently, “there were 53 world leaders and we were all standing around getting ready to go out and line up and they put us in a particular order and I said to the person that came to position me, ‘Oh, so it will be boy-girl-boy-girl?’” she recalled.

“And they looked at me blankly, not realising I was just making a sarcastic joke with them. Looking around a room like that you do stand out.”

Prime minister Jacinda Ardern talks to Noelle McCarthy for Venus Envy: full transcript

Noelle McCarthy: In terms of gender representation, what does ‘getting there’ look like to you?

Well probably when it comes to leadership and representation, I won’t go to a school anymore, and be asked by the young women there, “What’s it like to be a woman in a place where there’s underrepresentation?” and “How do you overcome discrimination?” Because young women ask me that, and I find that interesting. Is that because they see it or they just anticipate it?

Because my experience, as a 37 year old women in politics, is that actually relative to other countries we do quite well, but more broadly what does it look like? It looks like a place where women have financial security, and personal security, where everyone has choices that aren’t determined by gender and that we stop having to ask the question around what we do to overcome some of these significant issues.

Legislation is one way to enact change, how important is culture though – culture change? I mean [Prime Minister Richard] Seddon, when he gave women the vote he was a canny operator, and he knew that there was a groundswell of political support for this.

Yes, and you’re right, legislation is but one tool and so when I think about things around pay equity, it’s an important tool _ you create the mechanism by which you rectify some of these issues.

And you know when you look at that landmark deal around homecare workers, legislation played a critical role to reinforce what I think was already a cultural shift. But when you talk about some of those other measures of women and equality, things like the fact that they’re more likely to experience violence, then of course we’ve had legislation that opposed that for a long time. We’re now trying to embed protections into other places like our workplace around being able to seek support if they experience things like intimate partner violence, but we also have to create a complete is zero tolerance for it, we have to build these notions of respect and healthy relationships, and that is a much wider discussion.

I don’t know if you agree, but it feels like to me there is a crystallization of anger among women – women are angry, they are angry not just all over the world, they’re angry in New Zealand.

You talked about violence, about the lack of pay equity – we read recently about the motherhood penalty, and that you earn less if you take time out of work. Where can you put the anger, where’s the place to put it?

And you know that anger I think is probably if you were to express it in a New Zealand frame, we are such a fair minded country that when we see something that is unfair, I think it really gets to our core, and some of the issues that we’re seeing are just a question of fairness. Is it fair that you experience that deduction in your lifetime earning because you’ve taken time out to have kids? Is it fair that because of the particular field of work you’re in that you can expect to earn less relative to others?

There’s a question of fairness and I think that speaks to New Zealanders psyche a little bit, but that anger, you know for me the anger side of things that’s when we’re getting to issues that are just basic respect.

And finally we’re seeing – well not finally, there’s always been rebellion against – but we’re now seeing this international wave of people responding to what I’ve always interpreted as just the use of power and a lack of respect for women. And that’s how I would really drill right down into it and sort of simplify it.

Personally speaking, does this make you reassess, I mean for me I had a moment I worked on the story for The Spinoff about Pavement magazine in Auckland in the early 2000s, and this reckoning in terms of gender relations has made me go back and look at issues and situations that I’ve been in that I took for granted – I didn’t question because that’s how it was at the time, do you have that?

Yes, and I think that I’ve even heard women who are a few decades older than me, do exactly the same thing and say, “Gosh you know, show me a woman who hasn’t experienced that.” And I think what’s happening now is we’re questioning how is it that we could normalize that? We shouldn’t normalize that.

But yes, I think you’d be hard-pressed to find a woman who hasn’t had an experience that they look back on now and think you know that fell into that category, and then start to do the assessment of why did I not say anything? How did it make me feel? What stood in my way of really questioning that behaviour?

Is there anything that stands out in your memory?

Uh, yes. You know there’s a couple of workplace experiences. … which I have to say as much as people always think politics is a really difficult place I think the thing that I’m really mindful of is actually every workplace will probably have stories, I don’t think there is an industry or workplace that would be free of it.

That’s probably, if anything, what my experiences say to me and also just the fact that if you feel like you’re a junior like you are finding your way in your organisation – if you’re young that tips the scale and that does make it hard to stand up.

So what was yours? Were you young at the time or were you in a position where you didn’t have as much power as–

I don’t, and again this is probably quite a New Zealand response, I don’t want to overemphasise it. Because relative to some of the experiences I see women sharing – they are devastating to read about – and mine was minor in comparison, but at least it gives me that insight that probably other women have of when there’s a power imbalance and you have those experiences it does make it quite difficult.

I remember being distinctly asked, not so many years ago, by someone via email to support a women’s mentoring programme, and I was really keen to do it. And I said yes and they sent through to me their speech notes of how they would introduce the work they were doing to support women in professional careers, particularly young women by pairing them up with women with more experience in the workplace.

I remember reading these notes and not having met this woman and some of the experiences she’d had in the workplace were horrific – just blatant sexual harassment – and I remember thinking in my mind, of who it was that I might meet on the other end. I literally thought I was going to meet someone who’d came through their career in the ’70s, and then I arrived and she was my age, and I just remember thinking that was extraordinary that I’d made that assumption that surely we’d progressed.

I remember saying that to her, that’s again what’s made me think every workplace will have someone with a story, and we cannot simply think that it’s particular industries that are affected.

There’s a momentum – it feels like there’s a momentum – to these movements, to these movements in women’s solidarity in particular Time’s Up, #MeToo, do you think we’ll keep it? And if so, what will come of it, you know these provide fulcrums for political change, don’t you think?

I think as long as those experiences are being had, we’ll keep it, I think what we need to do is then say, “Okay well, what next?”

You don’t want a movement of women continually feeling like that they need to tell their stories that then equate to nothing in real terms. And so that’s the question that I’m interested in asking, what next? I come back a little bit to, “How do we ever create a situation where anyone thinks that’s acceptable behaviour?”

And that to me comes back to that respect question, of how we treat one another, of conversations around consent and healthy relationships, and you know, these are things we should be talking about in our schools, in safe places, where we learn our social norms before people are entering into the workplace.

[Prime Minister] Seddon, I mentioned how he saw what way the wind was blowing in terms of women’s suffrage, what would you like to be pushed into as a leader?

Ha, that’s a good question. I push myself into quite a lot of things, what would I want to get ahead of before the change came anyway? Look, when it comes to issues around women, the legislative framework, in a lot of ways exists, but again we’re getting now onto some of those soft more cultural values issues. I think now with things like #MeToo of course harassment in the workplace, we already have the legislative framework to say that is not okay, but do we have the environment where people don’t perpetuate that kind of inappropriate behaviour, in the first place, and an environment within our workplaces where people feel safe to speak.

And so probably what we need to be pushed on is starting those conversations. I use the word, ‘the soft side’, but it’s probably actually the harder part of the conversation, the legislation is sometimes the easy bit and in a lot of ways it exists.

Probably the things I’ll keep being pushed on and what I’m trying to get ahead of probably are some of those challenging things out in the environmental space and wellbeing space and inequalities.

But they relate, don’t they?

They absolutely do, and so when I talk about financial security for women, when you’ve got a country where you have such high rates of violence against women, you want to remove every barrier so a women can make a choice, have a choice about her future. And so long as we have women over-represented in the low paid work or unsupported as carers, the choice is removed.

And that’s the nub of it. Because a lot of this anger I’m talking about that’s been crystallised, we’re hearing from white middle class women you know, you know women who are going on the marches and who are tweeting and who are writing the op-ed’s, but how does that change actually trickle down to women of colour, or women who are working on the minimum wage?

Yeah, and again, I probably haven’t thought through some of those different connection points, but I see the importance of the #MeToo movement but it does not change the emphasis that I, at a personal level, feel around issues of violence and financial security.

When did you realise that being a woman was going to affect the rest of your life? Or did you, have you had that moment when you go, ‘Oh this is different for me because..’

It’s probably a little bit different for me because I grew up in a religious environment, where those different roles were set quite early on, so I had an expectation that certainly by the time I was 30, and at least by the time I was 30, I would be married at had kids already, and I never actually thought about too much, about career. I thought I would go and I thought I would do work I enjoyed and it would be hopefully fulfilling, but it was never the emphasis, when I was growing up, because that just wasn’t what I thought would be the future for me.

I remember once my dad saying to me, that I would be 30 and unmarried, and I thought it was the most insulting thing you could possibly say to me, as a young person. Because in the world that I grew up in, if you were 30 and unmarried, then you were on the shelf. Life was over. So, I think probably my experience is a little bit different in that regard and it has – I’ve talked about this before – it has taken a bit of a readjustment for me because that hasn’t been my life, for a time I didn’t even know if I would have children in my life, and yet that was such a huge part of me growing up as a young woman.

But it’s become part of you as a political leader now, you know you were always frank about wanting a family.

Yes. Yes I was, I perhaps didn’t talk about it too openly in the beginning when I didn’t necessarily have the other part of the equation. I spent a long time early on in my political career being single as well, so my life just has not panned out, in any way, as a young woman how I would have expected it to. And that has taken some adjustment. Leaving a church that I was so closely connected to, which I still have huge respect for, in my twenties was a huge adjustment.

And yet things evolve, and things change, have you always been more of a sort of ‘show ‘em don’t tell ‘em’ type of feminist, Jacinda Ardern?

Yeah, probably. And, you know I’m a pragmatist as well, so when I talk about feminism I talk about equality, my view is men not only can be feminists, they should be feminists, and if they feel if they believe in basic principles of equality, then they need to get on board and start rowing as well. But I am a pragmatist, and so for me it’s about, it is about what we can tangibly do to fill those gaps if they still exist.

And what’s it like for you, because symbols are so important in these sorts of conversations – you know whether it’s front page of broadsheet or a placard or whatever it is – but you have a symbolic role as well as a very busy real role as a political leader. But what is it like for you when you’re at APEC or you’re in Buckingham Palace and you’re looking around and you’re not necessarily seeing counterparts.

I constantly underestimate the symbolism element, perhaps in part because I don’t dwell on it too much. I’m lucky enough to be in a country where I’m not unique, I’m the third female prime minister, when I go overseas it does become more obvious to me but actually often what becomes more pronounced to me is that I’m both a woman and a progressive. Because in the current political environment that’s also rare. When I was at CHOGM (Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting) there were 53 world leaders and we were all standing around getting ready to go out and line up and they put us in a particular order and the person that came to position me I said to them, “Oh so it will be boy-girl-boy-girl?”

And they looked at me blankly, not realizing I was just making a sarcastic joke with them, but looking around a room like that you do, you do stand out.

Is it lonely?

No, no perhaps because being it politics it always means I’m slightly out of proportion in terms of representation but actually even that’s improved. But actually you can equally walk into a business environment where that’s the audience, or a group of representatives in particular workplaces, and see that imbalance and know that there are other women experiencing the same thing.

And there’s a solidarity in that. You marched in the Women’s March – there’s a placard from that in the museum exhibition, there’s a woman holding up a sign that says, “I can’t believe I’m still protesting that shit.” What got you out there that day?

Yeah, I spoke at that march. For me that wasn’t about anyone particularly. The trigger for many people of course was the election in the United States – for me, it was… we have to be constantly vigilant, keep our own house in order.

And I spoke that day about those issues, of violence and financial security because they are… for me, yes I will always stand in solidarity for women globally, particularly around issues around maternal health and wellbeing – but we can never forget we need to get our own house in order too.

There’s an irony isn’t there? You mention Kristine Bartlett and the care workers, and that sort of huge shift in culture that had to happen before that could go through, it was almost as though women were being penalized for what they do well.

Yeah, and when you look at the care sector. That’s exactly probably how it felt to the care sector as well, and you know we’ve been talking about the priorities we have as a government, and we talk a lot about earning and learning.

I was sitting recently on a plane and I thought: that doesn’t tell the full story about what we value, about the way we use our time. And so now we have this mantra that our goal as a government is a place where everyone who is able is either earning, learning, caring, or volunteering.

If you’re caring, you’re playing a huge role, you are a huge part in our society, we undervalue that greatly. Whoever you are, whether it’s, you know, your partner Clarke who’s doing the caring – we should value that.

This content is brought to you by the Auckland Museum. On now, Are We There Yet? Women and Equality in Aotearoa celebrates the 125th anniversary of women’s suffrage in Aotearoa – but asks how far has New Zealand really come since women gained the vote? On display at the Auckland War Memorial Museum until Wednesday 31 October.