Justin Latif sits in on a district licensing committee hearing, to better understand how decisions are made about liquor stores.

Given the well-reported harm alcohol causes in South Auckland, one of the most influential bodies in this region is what’s known as the DLC: the District Licensing Committee, which decides whether new liquor stores can open.

Following complaints about how difficult it is for people to make objections to licences, Auckland Council’s Marguerite Delbet wrote a letter to Glenn McCutcheon of Communities Against Alcohol Harm addressing these concerns. Delbet, as council’s then-democracy services manager, promised new efforts would be made to ensure objectors would be made to “feel heard”, thanks to a “more inclusive approach” by those running the meetings.

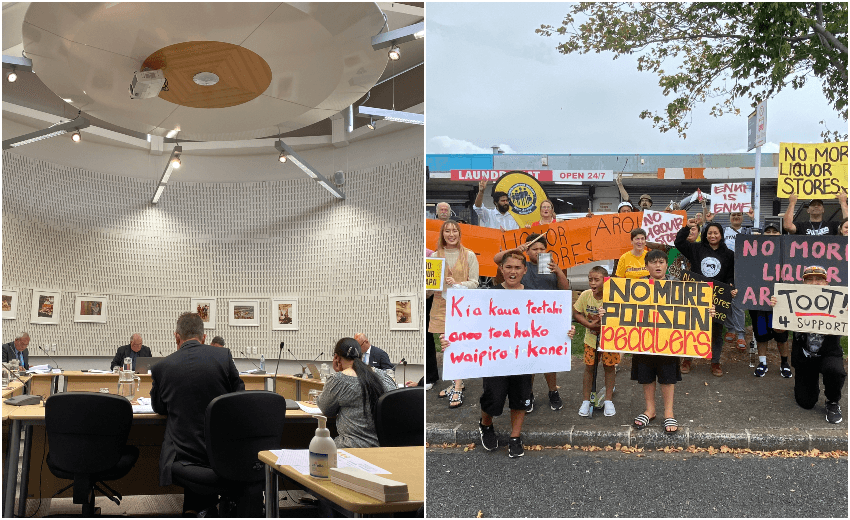

Had such an “inclusive” environment been implemented? I decided to attend a hearing myself.

The shades of justice

The latest application in South Auckland was for a new liquor store on Vine street, Māngere East. I attended the second day of the hearing, but also listened to 467 minutes of audio recordings from the hearings, plus skimmed over almost 100 pages of evidence and submissions.

In the lead-up the hearing, I also went to a community-led protest held outside the proposed location on a balmy Wednesday evening. Colourful chalk drawings scrawled on pavements and brightly painted signs waved by locals all decried the potential for a new store in their area.

A couple of weeks later, in two hearings at Auckland Council’s Tōtara Room, for the governmental reps, community objectors and the prospective liquor store owners in attendance, the colour palette was more hues of white and grey.

Like the tōtara, which is known for the girth of its trunk, the large squat room is round like a mature tree, with natural light breaking in from high windows. To break up the chalky shades, small photos of Pacific people in different poses adorn the walls, including a man processing fish in a factory, a woman weaving a mat and some brave youths trying to row a boat over a dangerous-looking reef.

After making a few light-hearted jokes, the DLC chair, Gavin Campbell, began the hearing by introducing the different parties in the room, which included the applicant, and a consultant assisting their application, plus a range of objectors (who had two pro-bono lawyers helping them).

Campbell then got a bit serious. He admonished one of the Māngere East locals for the rude way she had spoken to a council staff member, and then asked if anyone present was from the media.

“We don’t care if the media come,” he stated firmly. “But we don’t like to be ambushed. Wherever I’m the chair of a DLC, that question will be asked.”

Given these public hearings are recorded (how I noted this), it seemed an odd statement, but with these two matters out of the way, the meeting proceeded.

The early phases of the hearing focused on Sukhvir Singh and Gurpreet Kaur, who are married and co-directors of HS Judge Enterprises, the company under which the store would be run.

I felt sympathy for the couple as personal details of their lives and work histories were dissected by the various governmental agency reps seeking to ascertain their ability to run a store in an area known for poverty, crime and youth delinquency.

They were asked how many children they have. The answer: three, ages 8, 10 and 15. Who will look after them? Their grandmother, “who lives with us”.

What experience have they got working in a South Auckland liquor store? They had volunteered for two days at a friend’s liquor store in Ōtāhuhu.

The intrepid couple have also worked in an Indian restaurant in Hāwera, a Four Square in Rotorua and a superette in Flat Bush. But as the objecting agency reps kept reiterating they seemed to lack the “experience” deemed necessary to sell booze in an area like Māngere East.

The applicants’ lawyer Jon Wiles and accompanying consultant Robin Bryant are both tall, well-dressed men who spoke with the kind of confidence that comes from having appeared at many such hearings.

At one stage Bryant was asked if having a laundromat next to a liquor store was a risk. “In my society, they’re [laundromats] not needed, so I’ve got no idea what goes on in those places,” he said.

During another point in proceedings, Wiles stated that given his clients were part of the Sikh community, “you can draw an inference that they are kith and kin to people who undeniably have shown they are adept at owning and managing off-licences and are generally successful”.

Campbell interjected at this point, saying what community or faith a person comes from doesn’t necessarily correspond to how they run liquor stores.

The two most striking pieces of evidence came from the police’s alcohol harm prevention officer Keith Barker and Auckland Regional Public Health Service’s medical officer of health Stephen Galvin.

Barker was able to show that crime in the immediate vicinity around the Vine St shops had dropped 26% since there was a store in the area in 2016. He also noted that there had been a 17% drop in family violence call-outs and a massive 32% drop in serious assaults.

Galvin’s evidence carried far less good news. He pointed out that the area was one of the poorest in all of New Zealand, was among the most dense for liquor availability and also had some of the highest rates of alcohol-related harm for anywhere in Auckland.

Those giving evidence on behalf of the local community were a church minister, a politician and a retired woman. Māngere-Ōtāhuhu Local Board member Nick Bakulich described alcohol as a “stain” on the Pacific community. He said attending DLC hearings was beyond many of his constituents due to economic pressures. However, when he said he’d like to register an objection on behalf of the local board, the chair stopped him, reminding him that the board had in fact not sent in any objections, which in Campbell’s view was disappointing.

Bakulich then changed tack, saying the board’s objection wasn’t sent due to an administrative error, and that he was appearing in a personal capacity.

During her testimony, Reverend Emily Worman had to pause a number of times as the emotion of the moment began to overwhelm her. She shared how children had told her they are scared of seeing angry drunk people outside their homes and scared of seeing their own parents getting drunk and fighting.

“You know the research, you’ve heard how this will impact our community, but you will make the decision that we will have to live with, so I urge you to decline this application,” said Worman in a final plea to the DLC panelists.

The verdict

I attended the final five hours of the hearing in person. The weather outside was warm, with a gentle breeze. Inside it was colder, as the air-conditioning pumped incessantly in the background, while white fluorescent lights shone brightly on the stark proceedings. At times voices cracked with emotion and faces reddened with anger but the staid atmosphere helped keep any outbursts at bay.

It was as if the achromatic setting was able to hold back any vivid passions from bursting forth. And what struck me was that while South Auckland is such a vibrant and colourful community, it relies on pallid places like this to keep it safe. Does it work? In this case, after hundred of hours put in by locals, agency reps and two lawyers working pro-bono to provide mountains of evidence, the objectors prevailed. A few weeks later, on the morning of Good Friday, the news came through that the application had been declined.

Follow When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey’s essential weekly guide to the intersection of economics, politics and business on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.