After 15 years as an MP and six as finance minister, Grant Robertson is moving south to take on another challenge: the University of Otago. Having farewelled parliament, he caught up with Toby Manhire to talk tax battles lost, the Covid legacy and the lure of Dunedin.

Of the 20 years Grant Robertson worked at parliament – five as a staffer and 15 as an MP – the final lap, it’s fair to say, was not his favourite. After his close friend and colleague Jacinda Ardern quit as prime minister in the first breath of election year 2023, Robertson (having twice come within a whisker of the Labour leadership before) checked the gauge on his own tank and forwent the job, backing another close friend and colleague, Chris Hipkins.

Shortly afterwards, the income insurance scheme he’d sponsored was aflame on Hipkins’ big policy bonfire. Then the tax switch, complete with a new wealth tax, that Robertson championed alongside David Parker was unceremoniously snuffed out by the then prime minister via a statement from Lithuania. As finance minister, Robertson had to swallow a big boondoggle-flavoured rat in the form of the GST off fruit and veg policy. Oh, and the election was lost, calamitously, with Labour shedding almost half its 2020 votes. Can’t have been much fun.

“I mean, it wasn’t great,” he said. “But, on the flipside, right now watching what the government is doing is the very reason why despite those things not going the way I wanted them to, I was still there to fight. Because there was a lot more to fight for than just those policies. In the case of both the tax and the income insurance, I feel like they will have their day. Eventually, people will think we need to have something more comprehensive for a big economic shock when people lose their jobs. And on the tax, I’m convinced that will happen as well. Timing is everything in politics. And my timing was probably a bit off on those particular areas. But I still believe in them. And I still think they’re important. It’s important work.”

At times it must have stung, however, given the big job was for a moment his for the taking. “I thought about it. Obviously I thought about taking the job … But I stand by the decision. I knew I didn’t have inside me what I knew the job required. And I was happy to carry on and support Chris, and hopefully get us another team. But I don’t regret the decision.”

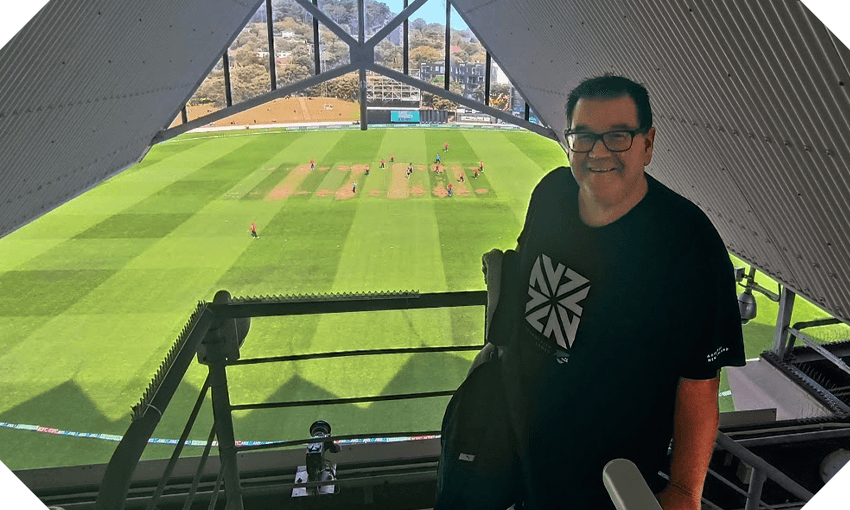

We were talking between clunks of leather on timber, blasts of music and orbiting sirens at the Basin Reserve (a ground which, Robertson was willing to put on the record in bipartisan accord with his successor as sports minister, Chris Bishop, is unequivocally the home of New Zealand cricket).

We’d chosen the location not just in the hope of achieving the first ever politics podcast episode recorded at a New Zealand cricket ground, but as a kind of bookend alongside another interview I’d done with him at Wellington’s great sporting roundabout, during a men’s test in 2016. Then, I asked the opposition spokesperson for finance which Black Cap he most resembled. “I’d like to think I’m a cross between Kane Williamson and Ross Taylor. I’m here to steady the ship. But I’ve been around for a while now, got a few games under my belt. There to do the hard work in the middle order,” he said, before straight-batting an attempt to extend the metaphor into Taylor’s fraught experience of leadership.

Today, it’s the third T20 between the New Zealand and England women’s teams. So which White Fern would Robertson – whose time as sports minister stood out for his advocacy of women’s sport and hosting a trifecta of women’s world cups, in cricket, rugby and football – resemble? “I think I have to identify with a retired White Fern, don’t I?” he said. “So probably Katey Martin,” he decided, nodding up from our seats in the RA Vance Stand towards the commentary box in the eaves where Martin was describing another New Zealand slump against England.

Political punditry for Robertson then? Not for a long time, he was quick to stress. Not given the status of his next gig, as vice-chancellor of the University of Otago, on the campus where he was once student president. There’s been a bit of pushback on the appointment of a non-academic to the position, but “that was pretty expected”, said Robertson. “There hasn’t been a non-academic in the vice-chancellor’s role ever, in 154 years. So I think that had to be expected. And maybe a little bit of [questioning around] can I make the transition out of politics to this, but I’ve got a pretty long history with Otago. And I like to think of myself, to use a Jacinda-Ardernism, as academic-adjacent.”

But back to tax. In his valedictory address, Robertson plainly underscored his view. “New Zealand’s tax system is unfair and unbalanced,” he told a packed chamber. “I felt like I needed to say it,” he said a few days later from a rather more ordinary, plastic seat at the Basin, his arms folded around the New Zealand Commonwealth Games logo on his T-shirt. “I mean, it’s no secret to anybody that I have had a couple of cracks at trying to address the unfairness and the lack of balance, both when we worked on CGT [a comprehensive capital gains tax plan] when we were in government with New Zealand First and the Greens, and then latterly in the package that David Parker and I were working on.

“Circumstances conspired to mean that those two efforts didn’t succeed. But it doesn’t change my view on that. And Chris Hipkins spoke a little bit about that in his speech that he gave on Sunday. And I think, you know, there has to be action in that space.”

The speech was the Labour leader’s laying out of values, which invited a discussion on the reforms required to a tax system which Hipkins assesses as both “inequitable” and unsustainable”. If only, I suggested, Labour had had an opportunity to address that with something like, you know, a historic one-party MMP majority government.

“Yeah,” he said with a brief wistful laugh. “And, as I say, I had a plan that was heading in that direction. Obviously, Jacinda had made some comments about what she was prepared to do and not prepared to do,” he said, in reference to the former prime minister’s guarantee, following NZ First’s full handbrake application, that she would never introduce a CGT. “We had to work our way through that. We wanted to get it right. I felt like we were heading in the right direction. Chris didn’t. And he was the leader. And I think we had to respect that. So, yeah. The three years of majority government was definitely a period where I felt we could make that change. But we just didn’t quite get there in the end.”

Which of the two – a comprehensive capital gains tax or a wealth tax – would he prioritise? “I think both are doable … Both would make a difference to that fairness question. Obviously, a CGT is a more known quantity, there are more of them in existence around the world. But they also come with exemptions and exclusions and things. A wealth tax is less tried, but does take to the super wealthy, for whom you feel that there really is a gap in what they’re paying. So I think either would be doable. And either would be a really good start to addressing some of the issues we’ve got.”

The challenge that towered above everything in the Ardern-Robertson years, of course, was the pandemic. The Covid response, which included a massive injection of money into the economy, is what Robertson will be judged on – for good or ill – for years to come. To take one impact, however: how does he feel today about the ripples of what might be called a K-shaped recovery, which saw the property-owning classes get richer while efforts to tackle poverty stalled?

That was a function of the fundamentals of New Zealand’s economy, he said. “Unless we did an intervention that fundamentally changed the nature of the New Zealand economy, the people who were in a strong position were going to do well … We were trying to hold still. We were trying to make sure that people kept their jobs, that businesses stayed afloat. And as a result of that, the status quo got expanded, almost. And the Reserve Bank do make decisions independently about what they’re going to do. They … injected money supply into the economy. The banks then lent that money, in the same way that they always lend money, largely to property. So in the absence of an intervention that undid that very, very deep-seated structure of the New Zealand economy, that was one possible result.”

He said: “I accept it. I accept that property values did inflate. Again, we were in the unknown. We had no idea what was going to happen. We were trying to cover all our bases. And ultimately, when I put the scorecard together at the end, I’m happy with what we did.”

Among other things, Robertson is looking forward to being closer in Dunedin to his mum. “As I said in the speech, I have spent a lifetime trying to match my mother, in a way. She’s an extraordinary person, in so many ways: intellectually, compassionately, just as a person generally … A lot of the value basis that I have in that, and that my brothers have, comes from mum and her outlook on the world. And she’s still very interested politically …”

If he’s not available for punditry, then, perhaps she could take it on. “Tell you what, she would make a fantastic political pundit. I’m not sure the shorter form would be good for her, though.”

Follow Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts.