Self-governance is an idea that’s been advanced by indigenous peoples in countries around the world – including in Aotearoa.

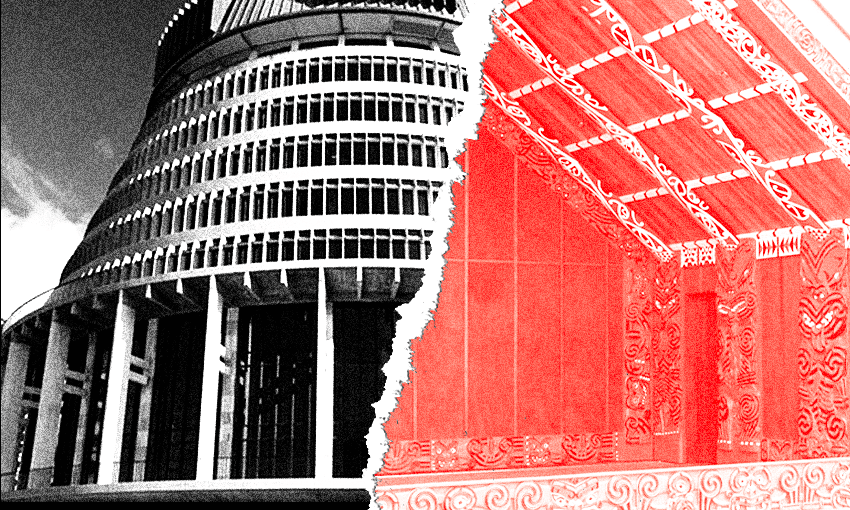

At Waitangi this week, Te Pāti Māori co-leader Rawiri Waititi called for the establishment of a Māori parliament in Aotearoa. Despite having Māori seats and MPs, it is no secret that New Zealand’s existing parliament is a Pākehā space, not an indigenous one. Which makes sense: our parliament, like most others in the Commonwealth, is based on the United Kingdom’s Westminster model. So how would a Māori parliament be different, and are there other indigenous parliaments worldwide?

Have we ever had a Māori parliament before?

Rawiri Waititi isn’t the first Māori leader to call for an indigenous parliament. Since He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni was signed in 1835, tangata whenua have thought up institutions mirroring Western parliaments. But the phrase “Māori parliament” is predominantly associated with the 1892-1902 pan-tribal “Kotahitanga” movement, which aimed to promote Māori interests, like stopping land theft. Although some Pākehā politicians attended its sessions, Wellington never officially recognised the legitimacy of this movement. Te Kotahitanga had two bodies: an upper house (Te Whare Ariki) and lower house (Te Whare o Raro). While modern Aotearoa only has one parliamentary body, it is not unusual for nations to have two, including the US (Congress and Senate), historic New Zealand (parliament and the legislative council, abolished in 1951) and many others.

Te Kotahitanga had a chairperson, prime minister equivalent (premier) and speaker of the house, which were three of its 140 positions – 44 in Te Whare Ariki and 96 in Te Whare o Raro. Members of the latter were voted on during national elections from four constituencies (Ngāpuhi, Te Tai Hauāuru, Te Tai Rawhiti and Te Waipounamu), and they appointed Te Whare Ariki representatives. Te Kotahitanga lacked a central parliamentary precinct, like Wellington. Instead its location changed regularly, with purpose-built wharenui sometimes being erected. Annual hui were held 10 times in its 10-year existence across Pākirikiri, Pāpāwai, Rotorua, Taupo, Waiōmatatini and Waitapu.

What other entities resembled a Māori parliament?

Te Kotahitanga wasn’t the first nor the only Māori body resembling a Western parliament. When northern chiefs signed He Whakaputanga in 1835, they agreed to meet annually in autumn for a congress to enact laws, uphold justice, order and peace, and regulate trade. While the congress never officially met, it is the first Māori parliamentary proposal. These proposals were also not just created by tangata whenua, as the government set several up.

In 1860, many rangatira attended a special government-convened meeting at the Kohimarama mission station (at modern-day Mission Bay). The most significant discussion at this “Kohimarama conference” was governor Thomas Gore Brown’s proposal to condemn Taranaki iwi for fighting the Crown. The government also tried to set up “Māori councils” on three occasions, including a failed attempt right after the Kohimarama conference. Te Kotahitanga Hou, the first successful attempt, started at the end of the 1800s, effectively ending the Kotahitanga parliament. The most famous example is the New Zealand Māori Council, which was created in 1962 and still exists today. Its original mandate was the economic and social advancement of tangata whenua and today it advocates on behalf of Māori, sometimes legally, regarding Treaty issues. All these council movements shared similar processes, for example electing representatives geographically or tribally.

Several other Māori-led examples existed, including one historians acknowledge as the successor of the Kohimarama conference. In 1879, a parliamentary group met in Ōrākei for the first time at the Kohimarama wharenui. This “Kohimarama parliament” met several times until 1889, when the idea for Te Kotahitanga started gaining popularity. Another indigenous parliamentary movement occurred at Waitangi between 1881 and 1890, which had a purpose-built wharenui named Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Te Kiingitanga historically had a parliament, too, called Kauhanganui. Established around 1890 and led by the Māori king, it had two houses, a ministerial council (including a minister of Pākehā affairs), and tribal representatives. This Kiingitanga body was the longest-lasting Māori parliament, meeting well into the 1920s. Seven decades later, at the Kiingitanga capital of Tūrangawaewae marae, the National Māori Congress was established to represent 37 iwi. The congress had a similar mandate to the NZ Māori Council – to represent Māori views on relevant issues – but was independent from government oversight.

Are there any international examples?

Not only is the idea of an indigenous parliament not a new concept in Aotearoa, it’s familiar in a number of places worldwide. Nordic countries Finland, Norway and Sweden have parliaments for their Sámi indigenous groups. Sámi parliamentarians are elected every four years to provide indigenous input into governmental policy in these three Nordic nations. (Sámi also vote in and can put themselves forward for national elections.) However, their role is limited: they aren’t self-governing entities that pass independent laws, but they do control their culture and language. While Sámi parliaments are, therefore, more consultative than legislative, they have directly influenced policy at the national government level to further their interests and protect their people, culture and way of life.

Fully fledged indigenous parliaments are much rarer in New Zealand’s fellow English-speaking colonised countries. Last October, Australia voted down its Voice referendum, which would have created the closest thing our neighbour has ever seen to an indigenous parliament. The “First Nations Voice” would have been an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander body advising government policy if the referendum passed.

What is the future of a Māori parliament?

The groundbreaking Matike Mai Aotearoa report on constitutional transformation found that to reckon with colonisation and honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi, a Māori political assembly must coexist alongside the Crown parliament. Despite that finding and recent calls from tangata whenua leaders like Te Pāti Māori co-leader Waititi to introduce a Māori parliament, the government (no matter whether Labour or National-led) is less than enthusiastic about sharing some of its power. But as the historical examples of Māori parliaments prove, tangata whenua don’t wait for Pākehā permission to create these sorts of bodies.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.