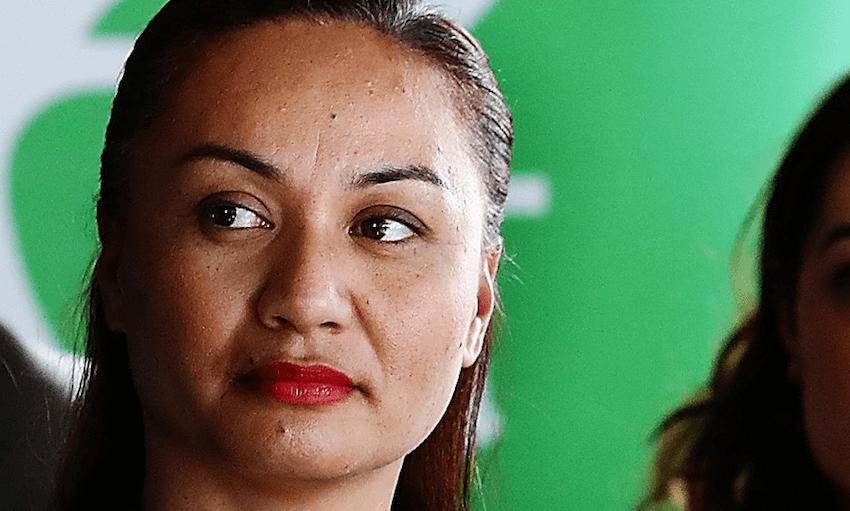

The Greens are often condemned for being too radical, and the claims have been flying thick and fast since the election of new co-leader Marama Davidson. But, she tells Alex Braae, she wears the term with pride.

Marama Davidson doesn’t often raise her voice, or thump the table to make her point. But despite her relatively reserved style, she’s risen to being the co-leader of the Green Party in less than three years in parliament. And her margin of victory over Julie Anne Genter, who is minister for women and associate transport minister, was immense – 110 delegates to 34.

That it was such a big win was a surprise to everyone who picked the race as too close to call. Green members found her to be an “authentic voice who has been standing up for a long time”, says Davidson in an interview at Spinoff HQ the morning after her win. “They’re trying to overturn the way we run government and politics, and I think that’s the mandate I was voted in on.”

That desire to overturn politics is partly why the tag of radicalism has been attached to her, and her supporters. There were well publicised threats by a small number of members to quit the party if Davidson lost. Some activists from other leftwing movements also joined the party and supported Davidson when it became clear a contest would be on, following former co-leader Metiria Turei’s resignation. It’s meant plenty of political commentators – some impartial, others anything but – have accused the party of swinging too far to the left in selecting Davidson.

When asked if the Greens have a communication problem with speaking the language of the press gallery and commentariat, Davidson laughs. “I don’t know what their problem is,” she says rolling her eyes slightly. Her view is that the positions she campaigns on are the true common sense positions.

“I’ve been talking about how I gave birth to my babies in Middlemore Hospital, which has sewage, literal shit and mould coming through the walls. How radical would it be to just make sure our hospitals are properly funded?

“What I do find radical is an economic system where the City Mission is full, but two men have more wealth than the bottom 30% of the country. So if that’s what I’m going to be labelled with because of the visions of life we can all have here, then I’m fine with that.”

More progressive than Labour

The fundamental problem for the Greens in government is that they run the risk of being obscured by Jacinda Ardern and Labour, and being out-manoeuvred by Winston Peters and New Zealand First. Since the birth of Jacindamania during the 2017 election campaign, the Greens’ polling numbers have taken a serious hit, and haven’t improved in any noticeable way.

Marama Davidson says the responsibility for the Greens is to push the government in a more progressive direction. She cites the abolishment of letting fees on rental homes as an example – it was a policy first championed by Metiria Turei. But in all of the publicity around the announcement, Labour’s housing minister Phil Twyford was front and centre. The Greens had effectively been written out of their own history.

The confidence and supply agreement between Labour and the Greens promises that the parties will deliver a “transformational” government. The wording echoes a line used by Metiria Turei at a campaign stop in Ōtara last year – that a vote for the Greens would “create a good government, not just a different government.”

The Greens have, by Davidson’s own admission, never prioritised getting out the vote in lower income, and more heavily Māori and Pasifika communities. The 2017 swing against the Greens in electorates like Māngere and Manukau East was less damaging than the average losses the party suffered across the country, but the vote share still started from a vanishingly small base in those electorates.

Marama Davidson also isn’t ruling out running to win in a Māori electorate at the next election. She stood in Tāmaki Makaurau in 2017, placing third behind Labour’s Peeni Henare, and the Māori Party’s Shane Taurima. But despite the standard Green strategy of only campaigning for the party vote, her personal vote was far stronger than the party vote.

It’s a calculation that may need to be made to save the party if their polling doesn’t improve before the 2020 election. Winning a seat could be a lifeline should their party vote fall under the 5% threshold, and co-leader James Shaw won’t win Wellington Central while Labour’s finance minister Grant Robertson holds the seat.

But many politicians before Davidson have tried and failed to mobilise the so-called “missing million” of voters – those who out of apathy, economic circumstances and cynicism don’t bother turning up to the polls. Davidson is aware of the scale of the challenge, saying it will take more than one election cycle worth of outreach work.

Davidson does think it can be done, in part because she has lived in the same circumstances as those she wants to reach. “I think we’ve got a unique opportunity for me to talk about those issues in the corridors of power, and also be on the ground with those very groups and communities, and a smart way for us to make the most of our resources.”

Foreign policy outsiders

The starkest difference between the Green Party to the rest of the parliamentary consensus comes in foreign policy. Pacifism is enshrined in the Green Party charter, and Davidson says each foreign policy challenge should be taken as an opportunity for the Greens to be seen as the most progressive party.

“We don’t believe foreign military intervention is the best way to achieve peace. So we’re not just being progressive for the sake of having a different opinion, it goes right to causation.”

On one current example – the recent clashes between Israelis and Palestinians on the Gaza border, which in the last two weeks have resulted in more than 20 Palestinian deaths – she is unequivocal about where she stands. Davidson was briefly detained in Israel back in 2016 while part of an aid flotilla to Gaza – described by then-PM John Key as a “less than perfect look” for New Zealand to have an MP be part of such a project – a view probably shared by the vast majority of career diplomats at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Davidson’s view then, and view now, is that the clashes are characterised by “disproportionate, brutal killing and violence by the Israeli state, to the Palestinians.” She says Israeli troops were “shooting and killing unarmed protesters”.

“The majority of those thousand marching are marching peacefully, but that tiny proportion who are showing aggression, it’s not even. When I’ve tried to speak out about that, it’s tough, so I understand the difficulty of speaking out on it, but the Greens have always been proud of standing up for human rights internationally.”

It could prove to be a flashpoint between the Greens and foreign minister Winston Peters, who is perceived by Israel’s leadership as more supportive than other New Zealand politicians. But only the Green MPs who hold ministerial roles are bound by collective responsibility, and only then in relation to their portfolio areas. Green MP Golriz Ghahraman, who spoke at a solidarity rally for Palestine over the weekend, has made numerous criticisms of New Zealand’s foreign policy consensus since arriving at parliament. During this term, the Green Party stood apart from parliament in opposing the CPTPP trade deal, and with an increasingly chaotic world, it’s unlikely to be the last time they have to make tough foreign policy choices.

Outside politics

Marama Davidson is a qualified aerobics instructor, which may have given her the people-wrangling skills for a career in politics. She needed part time work while juggling single motherhood and university, so got herself qualified and taught classes at Les Mills. She’s long been passionate about the outdoors, but hasn’t had a lot of time recently for it.

The last time she had a night off, she says she watched Netflix (Queer Eye, for anyone wondering) in bed with her dog, a cup of tea and some chocolate. She played up it being a “shameful” way of spending a free evening, but she probably needn’t worry too much about it being repeated any time soon. With the Greens trying to launch a new direction for the party, and Davidson trying to balance leadership, parliamentary and activist responsibilities, there probably won’t be too many nights off between now and the next election.

This section is made possible by Simplicity, New Zealand’s fastest growing KiwiSaver scheme. As a nonprofit, Simplicity only charges members what it costs to invest their money. It already has more than 12,500 plus members who, together, are saving more than $3.8 million annually in fees. This year, New Zealanders will pay more than $525 million in KiwiSaver fees. Why pay more than you need to? It takes two minutes to switch. Grab your IRD # and driver’s licence. It really is that simple.