Critics say it paves the way for Australian-style detention policies. Supporters say it’s merely procedural. Who’s right?

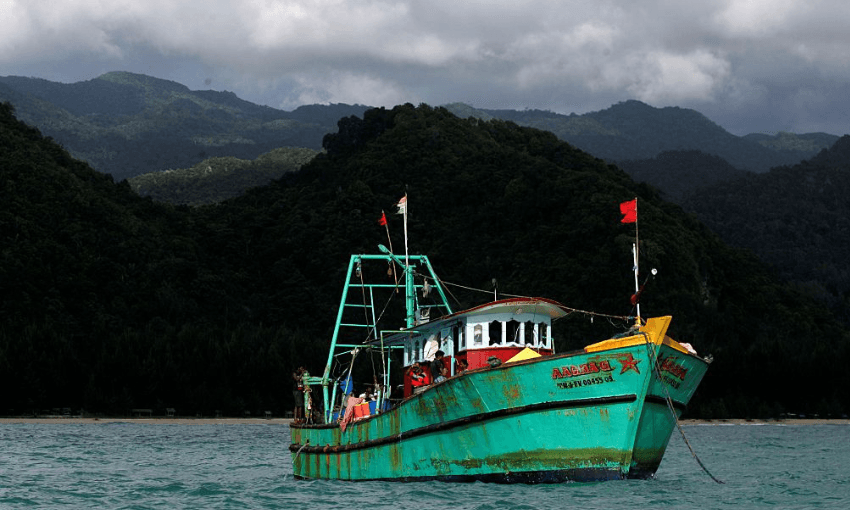

Dozens of refugees or asylum seekers arriving at once is common in European countries and Australia, but it’s still largely unknown on New Zealand shores. But mass arrivals are a highly sensitive issue, with proposed changes to the government’s ability to detain arrivals raising the spectre of Australia’s widely criticised long-term detention policies.

Still, legislation for dealing with mass arrivals has been on the books for years, and the current proposed amendment doesn’t negate human rights protections in other parts of the law. The government’s proposed changes might be seen as simply procedural, allowing an already existing piece of legislation to function as intended.

Here’s a brief explanation to help you understand what the proposed legislation says.

What is the Mass Arrivals Amendments Bill?

The Mass Arrivals Amendment Bill is a list of proposed changes to New Zealand’s immigration law. It’s high up on Parliament’s order paper, which means it will be debated at its second reading soon.

New Zealand’s 2009 immigration act had some provisions for mass arrivals, and the law was further updated in 2013 under a National government. The law currently says that a mass arrival of people, defined as 31 or more arriving in New Zealand at once without visas or permission, can be detained for up to 96 hours (four days) without the need for a warrant. This is supposed to allow those people time to find legal representation. Under normal circumstances, it’s not possible for the state to detain you unless there is a warrant that gives them a reason to do so.

The amendment that is up for debate allows for arrivals to be held for up to seven days while waiting for a mass arrival warrant from a judge. If that isn’t practical, the judge can adjourn proceedings for up to 28 days after the initial application for a warrant is made.

According to a Beehive press release from Michael Wood, who was minister for immigration at the time of the bill’s introduction in March last year, the amendment is simply “procedural”, allowing potential detainees to have more time to get access to specialised legal support.

In his speech at the first reading of the bill, Michael Wood implied that it would stop people smugglers. In his media release he said the bill would make it easier to uphold the human rights of people arriving in a mass arrival and would clarify that they need to apply for visas as soon as possible.

After passing its first reading under Labour’s majority last March, the bill was sent to select committee to hear submissions and evaluate the proposals. National and Act also supported the bill, while the Green Party and Te Pāti Māori voted against it.

What happened at select committee?

There were more than 300 submissions, most of which were opposed to the bill. The select committee at the time was made up of three Labour MPs, two National MPs and one Green MP. The Labour MPs ultimately voted in favour of the amendment and the Green and National MPs against. Instead of delivering diverging reports and voting for a recommendation, the committee unanimously supported a joint report that said they couldn’t decide on whether the bill should become law or not. As this report from Stuff’s Glen McConnell explains, this is very unusual.

Andrew Little, who was minister of immigration at the time of the select committee’s joint report, said the committee was “being wilfully blind” to the possibility of asylum seekers arriving by boat, and criticised them for announcing their decision without hearing further advice from immigration officials.

Little released the cabinet paper from June containing the advice from officials he had received about the bill. The advice takes particular note of the public response, and suggests that messaging around already-in-place human rights protections for potential asylum seekers needed to be communicated better to the public.

It emphasised that “planning for a mass arrival event has never included prison”. Describing the nature of the submissions, the advice said that the “the submissions overall indicate significant misunderstanding about the purpose of the legislation”. The proposed law neither amounts to arbitrary detention nor prevents members of a mass arrival group from claiming refugee status, the advice noted.

So what happens now?

Before the election, Chris Luxon was dismissive of the bill, calling it “a solution looking for a problem.” But now, privy to confidential official advice and clearly willing to sponsor the legislation as a government bill, he appears to have changed his tune. A spokesperson for Erica Stanford, minister of immigration, confirmed to The Spinoff that supporting the bill is part of the government’s legislative agenda.

It’s a case of history repeating. As noted by Michael Woodhouse, Labour had been vehemently opposed to the initial mass arrivals law in 2013, arguing that it was unnecessary since it was so unlikely that boats would reach New Zealand, but once in government “the worm turned”.

Has New Zealand ever experienced a “mass arrival”? How did the government respond?

There’s been speculation that particular boats would end up in New Zealand for decades. There was a suggestion that a boat from Honiara was heading for New Zealand in 1999, leading to a rushed piece of legislation to allow those on board to be detained, but the boat went to Canada instead. According to information released to RNZ by Immigration New Zealand in 2023, there have been other documented attempts of boats allegedly bound for New Zealand, including in 2013 and 2019, but none have ever actually arrived here. In most cases the people on these boats have disappeared.

It’s not clear if immigration authorities have provided information to the government that points to mass arrivals as something which could realistically happen in the next few years in Aotearoa, or if successive governments want to alter the legislation just in case. During the first reading of the bill last year, Michael Wood refused to answer questions about this, and several parts of the initial cabinet paper have been redacted. Official information obtained by RNZ shows that while the government has purchased spy software developed by an Israeli firm to monitor potential asylum seekers trying to reach New Zealand by boat, they have barely used it.

Why are people so concerned about the future of mass arrivals, in New Zealand and elsewhere?

To its opponents, the Mass Arrivals Bill is a way of ushering in a piece of legislation that could damage human rights by placing people in detention while the issue isn’t an urgent part of public debate. To its supporters, it’s a pragmatic law that could help ensure courts wouldn’t take years to respond to a possible mass arrival. Advice provided to Cabinet before the first reading of the bill last year cited a mass arrival from Sri Lanka to Canada in 2010; a decade later, some of the nearly 500 refugees aboard were still in limbo.

The conditions that force people to leave their homes, including climate crisis, war, political instability and government targeting of specific groups are just as prevalent now as in 2013, when the mass arrivals legislation was first introduced. The UN estimates that 110 million people are currently forcibly displaced around the world. Whatever the result of this amendment bill in New Zealand parliament, it’s possible refugees and asylum seekers will eventually try to come directly to Aotearoa. How we treat them is being determined now.