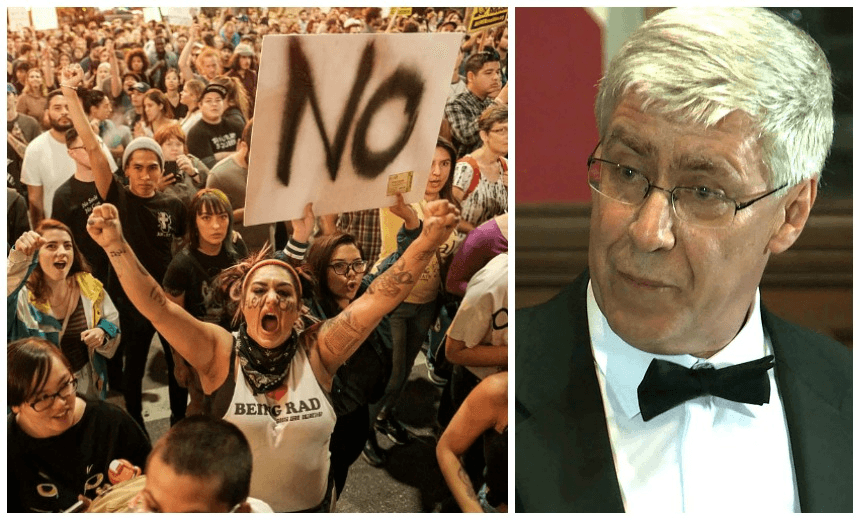

What’s the best response to the threat to political norms – and, some say, to democracy itself – posed by President Donald Trump? According to the NZ-born, New York-based political philosopher Jeremy Waldron, it’s civility, reason and restraint. Max Rashbrooke talked to him during a recent visit back home.

If the world is going to hell, you wouldn’t know it by looking at the lobby lounge of the Intercontinental. The venue for my interview with professor Jeremy Waldron is Wellington’s premier hotel, and all is calm, glass, comfortable people and cushy sofas. But Waldron is worried. On his mind is the way politics has, as he sees it, been hit by “a startling collapse in civility”.

A New Zealander by birth, Waldron has spent much of his life in the world’s most distinguished academic institutions. Sometimes described as one of the world’s foremost political and legal philosophers, he was previously Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at Oxford University’s All Souls College, and is now University Professor at the New York University School of Law.

He is back in his homeland thanks to the Maxim Institute think tank and the Law Foundation, who’ve brought him over to give a lecture on the prospects for restoring civility to political discussion. Civility, Waldron says, is about abiding by the rules which distinguish enemies from opponents. People have to see their political opponent “as a fellow citizen, committed like you to the common good. You need to have modes of engagement that allow you to argue, disagree, contradict each other, even involve a degree of political combativeness, without necessarily moving in steps that would intimate possible violence, possible personal denigration.”

People in political debates need to maintain respect, be able to “project” themselves into another’s shoes, and understand that a reasonable person can come to different conclusions to their own. This does not mean, Waldron is at pains to point out, that people should moderate the content of their views – just the way they express them. “Civility doesn’t involve diminishing the level of opposition, it doesn’t involve diminishing the level of condemnation. But it involves finding practices, forms of words, forms of engagement, that allow some degree of respect.”

For him, one of the great dangers is the “corrosive culture of suspicion” that envelops modern political discussion. By this he means the way that people, instead of engaging with the details of someone’s argument, dismiss it out of hand as being motivated by envy or selfishness. “The attribution of motives is, I think, a serious problem because it indicates that what’s being said in the disagreement doesn’t matter in of itself. Everything is about self-interest or the prejudice you are ascribing to them.”

This, Waldron feels, indicates “a rather simpleminded, almost infantile view about what disagreement is. [It’s the view that] there can’t be disagreement unless it is motivated by something other than the terms of the argument itself.”

The stakes, he argues, are high: a loss of civility threatens not just the quality of debate but even the idea of the democratic handover of power. People take for granted the idea of peaceful political coexistence, “but we don’t realise how rare it has been in human history, and how rare it is in the world, that after an election defeat, the party losing doesn’t feel that it has to go into the mountains.” That peaceful transition is not immediately under threat in New Zealand or in most advanced democracies. “But we have begun taking some of the steps that … move us towards a situation where we are less and less often having peaceful electoral transitions.”

The US political situation weighs heavily on his mind: he cites the disputed 2000 Bush vs Gore election, the ‘birther’ campaign – fostered by Donald Trump – that questioned Barack Obama’s legal status as president, the impeachment of Bill Clinton, and Trump’s own false claims about voter fraud. But he also sees danger in the questioning of Trump’s legitimacy: the talk of impeachment and treason, the suggestions he could be dismissed under the 25th Amendment, the amateur diagnoses of mental illness. Indeed he makes a slightly unexpected defence of a man many describe in apocalyptic terms. “It’s six months into a presidency by someone who has little experience, who is flailing around, and there isn’t a whole lot of toleration for his rather inept efforts in the administration.”

But doesn’t Trump behave in a way that threatens the basic norms of civilised American politics? “He does indeed. This is a two-sided incivility. And I think the point there is that the problem is not solved or mitigated by one side saying that the other side started it, as though the issue were blame rather than conflict.”

This, of course, is a statement likely to enrage the anti-Trump movement, who see themselves as responding to a series of bizarre and repugnant actions that Trump did, indeed, start. “The question is what is achieved by saying that … Those who say that have to understand that their opponents will say the same thing. And secondly, the problem of incivility is not solved by saying that Trump started it.” Whatever Trump’s failings, behaving in uncivil ways will just harm the political fabric that people see themselves as protecting, Waldron argues. “There are certain things you must not do, because the damage is done to the republic, whether you started it or your opponent started it. So I do think this business of moving quickly towards thinking of impeachment is a mistake.”

Waldron’s “exemplar” of civility is the Republican senator and former presidential candidate John McCain. So what does Waldron think of the way McCain is routinely mocked on social media for responding to every bizarre thing Trump does by saying he finds it “troubling”, but nothing more?

“People will have different reactions from him. They will find ways to condemn what he has said because he is a Republican … It’s very easy to make fun of it, and one wishes that those who were making fun of McCain were thinking a little bit about the character and generalisation of their own position” – a position that, Waldron says, is often “self-righteousness leading to cynicism”.

Waldron insists he is not opposed to emotion, or “very great moral concern”, in politics; it’s just that it needs to be restrained. He draws an analogy with the courtroom, and the restraint that allows good lawyers “to convey passion, the essence of the case of their client, and it’s one of the great arts of rhetoric to be able to do that within the four corners of the established system of engagement.” The great courtroom and parliamentary speeches of the past are Waldron’s ideal marriage of passion to reason.

At this point, a thought arises: has he come across the term “tone policing”? “No, tell me what that is.” Well, I say, for a while now activists have argued that concerns about the “tone” of political argument are used to frame others as irrational and shield privileged listeners from hearing discomforting views. Waldron’s response is that civility “is largely a matter of tone. So one wants to hear why we should be indifferent to tone.” But even if well-off people can easily be civil, shouldn’t the anger and frustration of those affected by discrimination be heard? Shouldn’t they have a place in which to vent and, to use an old phrase, afflict the comfortable?

“Yes, maybe so,” Waldron says. But, he adds: “I don’t know whether politics should be set up so that such venting of anger would become a routine move.” Returning to the courtroom motif, he argues that the emotional content of victim impact statements is harming the judicial process. “Often family members of victims will come and condemn the convicted defendant … in bestial terms, calling them scum and insects, animals who deserve to suffer, and so on. And that we should in our courts be offering venues for that seems quite wrong.”

Civility is not for all situations, Waldron adds. It is not “an all-purpose personal virtue” but “a specific virtue for politics. Suppose both sides feel outrage, indignation and grievance, then how does politics proceed in that condition? How do we legislate in that situation?”

One can see what he is getting at. If politics has to end in a law change, or a rational, calculated policy paper, emotions have to be channelled somehow. But doesn’t his argument put the outrage of the comfortable on the same level as the outrage of those who genuinely suffer discrimination? “Nobody is talking about equivalence. All one is talking about is the indulgence of anger, deeply felt anger on both sides. The talk about ‘which is equivalent to what’ is a little bit like the childish talk of ‘he started it’. The question is not equivalence; the question is, ‘How does politics look when anger is indulged?’”

Once more the courtroom provides a model. Civilised society, he argues, has made criminal justice “not a matter of personal anger or revenge. It is not to be a place where vengeful anger vents itself. We have tried to substitute, not just complement, vengeance with criminal justice … And I believe politics needs to be understood in the same way.” Those who do not share this understanding draw his strongest criticism: “The person who believes that their passion exonerates them from the requirements of civility, the person who believes that their self-righteousness exonerates them from the requirements of civility, is the most dangerous person of all.”

People venting online, of course, would probably not agree that they were behaving dangerously, or like children. And convincing the average person that they need to argue in the manner of a courtroom lawyer is, Waldron admits, “a hard task”. But he thinks the process of child-rearing may help people get his point. “Everybody has to bring up children. Everyone has to civilise whatever fights break out among children. Everybody has to say to their child, ‘Well, go and ask them if you can use their toy.’ So we all have some familiarity with the forms and culture that make civilised disagreement possible.”

Is he, then, suggesting that in order to be civil, we need to grow up a bit? “I’m just saying that that’s one basis on which ordinary people do understand that we have to transition from simple, childlike violence to more respectful modes of interaction.”

In many ways, Waldron’s arguments are a defence of the classic liberal settlement, in the line of the philosophers and economists he references: Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, John Rawls. Though he has some reservations, he feels the basic democratic institutions – parliament, the media, the courts – are still sound. Some thinkers are questioning whether those institutions are in fact fit for the twenty-first century, and whether we are entering the “post-liberal world”, but not Waldron.

Unlike many commentators, however, he doesn’t reflexively blame social media for the world’s democratic ills, although that may be because he doesn’t use it very much. He’s seen enough to know that “some of the people who make use of it are relatively indifferent to civility” – a strong contender for understatement of the year – but hasn’t used his Twitter account for years. So he’s probably not on, say, Snapchat? “I barely understand what Snapchat is,” he says, with the air of a man quite happy not to be enlightened.

Rather than blame the media or other institutions, Waldron argues that we all bear the responsibility of becoming more civil debaters. But are we capable of that? “I don’t know,” he says. “I think chipping away at civility is the sort of thing you can do for decades but you don’t realise when the tipping point is coming. It’s a little bit like earthquakes. There will be tremors, but there’s no way of telling which is the big one.”

It doesn’t help that, in the US in particular, people have “sorted” themselves into homogenous communities – by religion, income, education and so on – and thus “are becoming increasingly unintelligible to each other. So there’s no guarantee that in 20 years, if we continue down the same path, we will have enough in common.” Civility, in other words, “could be one of those things which, once you lose it, you can’t get back.”

This content is entirely funded by Simplicity, New Zealand’s only nonprofit fund manager, dedicated to making Kiwis wealthier in retirement. Its fees are the lowest on the market and it is 100% online, ethically invested, and fully transparent. Simplicity also donates 15% of management revenue to charity. So far, Simplicity is saving its 7,500 members $2 million annually. Switching takes two minutes.

The views and opinions expressed above do not reflect those of Simplicity and should not be construed as an endorsement.