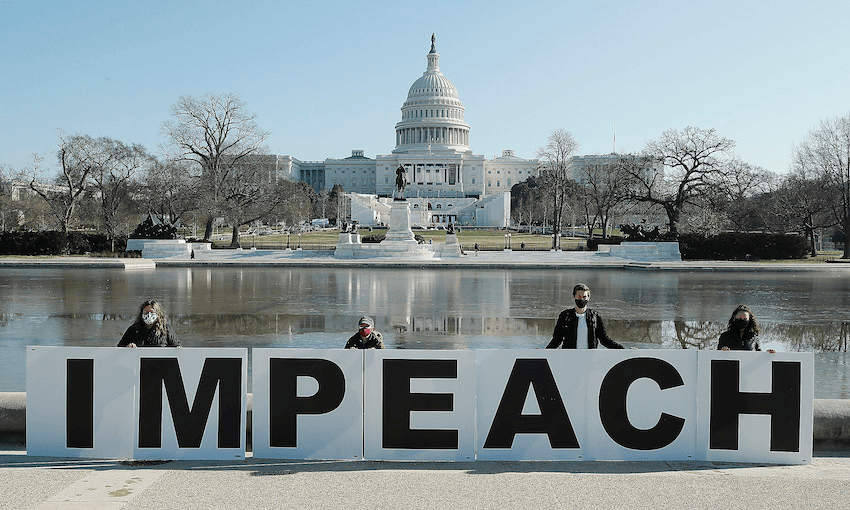

It’s been described as ‘pointless revenge’, but impeaching the president has a firm moral purpose, argues Michael Blake – setting a limit to what sorts of action a society will accept.

A House majority, including 10 Republicans, voted today to impeach President Trump for “incitement of insurrection”. The vote will initiate a trial in the Senate – but that trial will likely not be finished before Trump’s term of office comes to an end on January 20.

There is an open constitutional question about whether a president can be impeached after he has left office. A more basic question asks about the point of impeaching Trump. Conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt, writing in The Washington Post, described the entire exercise as “pointless revenge”.

“It isn’t principled, it isn’t concerned with justice and it isn’t concerned with the future,” he stated.

As a scholar who writes about the moral justifications of social and legal institutions, I argue that there may be good moral reason for this impeachment – even if it cannot be completed before Trump leaves office.

Impeachment is not a criminal procedure; it is generally described as “quasi-criminal” in American law.

The philosophical justifications given for the institution of criminal law, however, might help us understand the purposes this impeachment might serve.

Impeachment and criminal law

Criminal law can serve a variety of functions. It incapacitates the criminal, through incarceration; it serves a retributive function, by forcing the criminal to experience punishment proportionate to the crime; and it expresses a particular view about the limits of moral diversity, by setting a limit to what sorts of action a society will accept.

Incapacitation is likely a bad justification for the impeachment of an outgoing or former president. Incapacitation is intended to stop a criminal from repeating his or her offence. The offence grounding the president’s impeachment, though, was an act of speech, one the article of impeachment describes as “incitement of insurrection”. A president who is impeached and removed from office is precluded from holding federal office in the future; that, however, does nothing to remove the power of Trump to speak.

Retribution is similarly unpromising as justification for impeachment. The “punishments” here – including the loss of Secret Service protection, office space and public funding – hardly seem adequate, if they are conceived of as punishments for one who has incited an insurrection.

Punishment as moral condemnation

The final function of criminal law, though – one emphasised by philosopher Joel Feinberg – is likely better able to justify an attempt to impeach an outgoing president. Criminal law, for Feinberg, is intended to mark out the limits of moral disagreement, through a symbolic statement condemning certain sorts of acts as immoral.

Citizens in a democratic society do not need to agree about political morality. They can recognise their political opponents as entitled to their views – however mistaken each side takes those alternative views to be. Conservatives and liberals have often regarded each other as wrong, but nonetheless members in good standing in their political communities.

There are, however, some points at which a society makes a shared statement that a given sort of practice or act is not politically respectable – and the criminal law is one means by which that statement is made. As Feinberg notes, imprisonment is not simply an unwelcome punishment – it is a symbolic statement that the criminal has done something of which he or she ought to be ashamed.

The criminal – or the impeached – might not actually feel ashamed. The function of the criminal law, however, is to say that he or she ought to feel ashamed, and that those who do that sort of act are outside the realm of normal moral disagreement.

Politics after violence

We might see this sort of function by examining how legal institutions have responded to much more serious forms of political wrongdoing. The Nuremberg Tribunals, most famously, put the Nazi hierarchy on trial, for aggressive war and for crimes against humanity.

The punishments meted out – ranging from 10 years in prison to a relatively quick death by hanging – would seem grossly inadequate, if they were intended to match the moral gravity of genocide and forced labor.

The best justification of Nuremberg, though, looked not to the Nazis themselves, but to those who might have followed in their footsteps. The trial was intended to identify the line past which political societies could not stray without being regarded as shameful – with an eye not simply on the present, but in the future.

President Trump’s wrongdoing is nowhere near as grotesque as that of the Nazis, and no purposes are served by pretending otherwise. The best moral purpose for his impeachment, though, might have some moral similarities to the functions of Nuremberg.

The move to impeach President Trump is an indication that there is a need to mark out, through a definitive statement, what no president ought to do. It will also set the moral limits of the presidency – and, thereby, send a message to future presidents who might be tempted to follow in President Trump’s footsteps.

This is an updated version of a piece published earlier on January 13.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.