With the National Party caucus looking more conservative than it’s been in a long time, Liam Hehir warns of the dangers of ideological factionalism, and why being a conservative party isn’t the same as being a party with conservatives.

Liberals seem to be something of an endangered species in the National Party these days. First of all, Paula Bennett, who was despised by the left but was one of the party’s crusading liberals, left politics after losing the deputy leadership. At the same time, Amy Adams retired only to subsequently un-retire. The very trendy Nikki Kaye also threw in the towel after serving part of the day as acting leader.

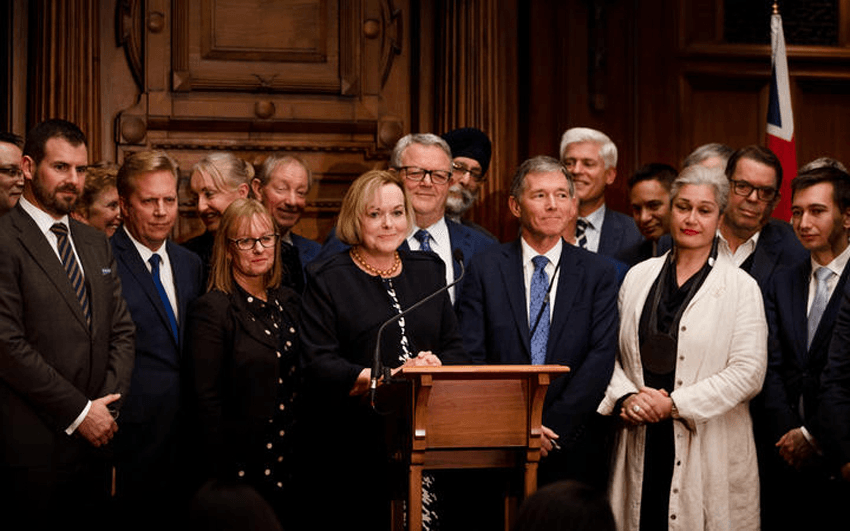

This leaves National Party liberals somewhat thin on the ground. Christopher Bishop and Nicola Willis are the standard-bearers now, you have to assume, and Scott Simpson is a reliable vote for liberalism even if he is a party man first and foremost. There remain quite a few liberal-ish members (including the new leader, incidentally) but on the whole, the caucus is looking like it will be more conservative than it’s been in a long time.

The degree to which ideology divides the party should not be overstated. There are other faultlines which in certain ways are more important. Geography, for example, provides competing interests between town and country and North and South Islands. More than any other factor, perhaps, is that personal ambitions and loyalties are part of the mix.

But it can’t be denied that differences in philosophical outlook play their part and might’ve become more important during the years of National’s opposition.

At this point, it’s important to carefully define what we mean by “liberalism.” It doesn’t refer to “socialism” – opposition to which the thing that most unites the various strands of the party. Within the context of the New Zealand National Party, liberalism refers to those who are liberal on what we call “conscience issues”. They tend to be, but not always, a bit more market-oriented and urban-based than the party’s conservatives.

The conservatives, on the other hand, tend to vote along more traditionalist lines on conscience issues and tend to be, but not always, a little more tolerant of economic intervention and rural-based than the party’s liberals.

As a political conservative myself, I have to say there’s nothing inherently displeasing about a more conservative front bench. The National Party is a collation of interests that from day one has included both libs and cons. There’s no reason why the latter should always be the junior partner given that they bring in most of the votes.

My warning, however, would be that it’d be dangerous for National to become a conservatives party rather than a party with conservatives in it. It’s better to share power in a party that governs more often than not than it is to be the dominant force in a party that reliably gets 35% of the vote.

The stirrings of ideological factionalism in the National Party is not something to be welcomed. Whether it’s entirely true or not, the coup against Simon Bridges was seen by some as the installation of a stooge by a bloc of MPs who knew they couldn’t win the leadership outright but could be the power behind the throne. The plotters may dismiss this as paranoia but even the fact of such paranoia would be a problem itself. In the same way, it would be very helpful if people associated with the party could stop talking up the idea of the cons splitting off and forming a tame client conservative party to provide a junior coalition partner.

The National Party is not an ideological movement. It is a political framework that allows members unified by their opposition to state socialism to pursue their various goals incrementally and co-operatively. Nobody ever gets everything they want but that’s a fact of life.

Judith Collins may actually be the best person to restore this sense of things. With few apparent fixed philosophical positions, she isn’t beholden to either camp. Her brand is built around her own force of personality. This can have its downsides, but the upside is that she can be trusted not to put her thumb on the scale for either camp. And that just might give National the time it needs to heal.