Labour says this will be the Covid election. National says it’s about the economy. There’s something big being missed in the middle, writes Justin Giovannetti.

It was the week the economy took centre stage. The scene was set in the pre-election fiscal update, which on Wednesday offered a sobering snapshot of what’s happening under the hood of New Zealand’s sputtering economy. But Treasury’s data points to a deeper problem that few seem keen to talk about.

The campaign promises from Labour and National that followed the Prefu have been focused on taxes, economic growth, projections of high deficits and worse than expected debt. It will be a bad decade for the country’s balance sheet and the debate between the two major parties is focused on questions of debt repayment schedules and who you should trust to pay creditors back quickly.

What’s missing is an honest conversation about what the fiscal update means for the average New Zealander. The picture from Treasury of the coming years is beyond grim: it is a blueprint for misery.

Under the government’s new projections, people will be poorer, opportunities will be more limited, communities will face increased pressure and home prices will continue climbing, unhampered by pandemic or recession. If you’re a millennial New Zealander and you haven’t purchased a home yet, this is as close as the government will come to telling you that part of the Kiwi dream is now dead and buried.

Those years of increased unemployment will be destructive, Treasury has warned.

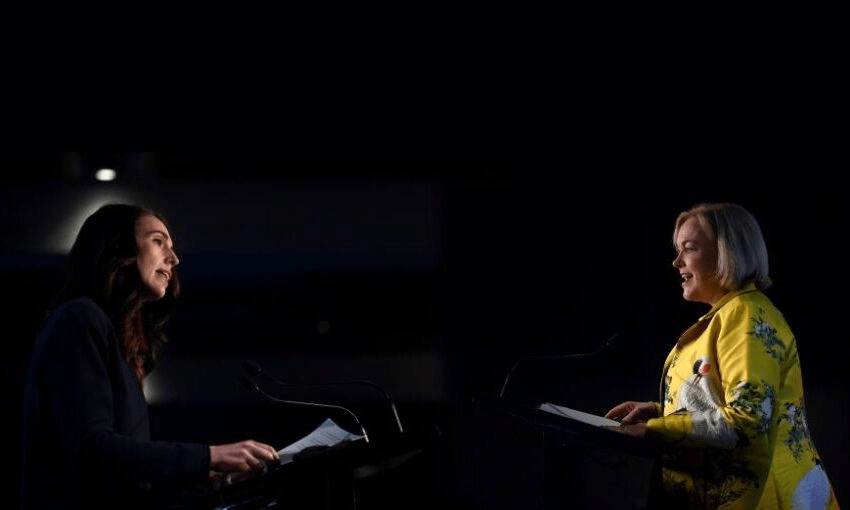

In the jargon of economists, officials wrote that “the persistent effects of the Covid-19 pandemic are expected to lead to a degree of economic scarring, leading to structurally higher unemployment”. You might not know what the term “economic scarring” means, but most people would recognise it when they see it in their own communities. It’s also one of Labour leader Jacinda Ardern’s greatest fears.

It means that once this current recession ends in months or years, the consequences will continue for decades. For most people, the loss of education achievement, whether from poorer child nutrition or the breakdown in families, as well as the loss of opportunity, will follow them for the rest of their lives. It means people’s futures will shine less brightly. Across an economy, it means we are all worse off.

Act will tell you that the economic update shows that the government will borrow $165.6 billion over the next decade. That’s not wrong. Labour will tell you that they won’t engage in austerity budget cuts which would make the situation worse. That’s also not wrong. National says we can grow our way out of it. That might be wishful thinking, but their plan is not dramatically different from Labour’s plan.

National announced yesterday that they’ll cut everyone’s taxes, temporarily, by adjusting tax brackets. It’s a quick fix and easy to reverse. It’ll make for a small gift over the next two years to people who keep their jobs. Labour’s plan is to add a new higher income tax bracket on the richest 2% of New Zealanders.

What none of them are actively talking about is the looming increase in inequality, as poor New Zealanders get caught between fewer jobs and growing expenses. At the same time the country’s richer citizens, benefiting from low taxes and the government’s economic support programmes, will grow richer still. This is a phenomenon being seen around the world, but New Zealand’s housing crisis makes it more acute.

Asked by reporters on Wednesday what she’ll do to tackle inequality, National’s Judith Collins said she would create jobs. That’s a good measure to reduce poverty, but it’s not a programme to ease society-wide inequality. A study from the University of California Berkley suggested inequality can be tackled through corporate reform to incentivise higher wages, tax reform with a significant capital gains tax, and building up the assets of working families. Neither of the major parties is even hinting at that.

On housing, Collins had a similar message. Asked if homes in New Zealand are too expensive, she quipped: “If you can’t afford it, it’s too expensive.” A generation of New Zealanders sighs. Her solution is to build more homes. “It’s simple economics, supply and demand,” her finance spokesperson Paul Goldsmith added. Except, it’s not always the case. That solution may have existed before a global investor class turned homes into investments, but despite a decade of sharply rising building consents, prices kept up a steady and steep march upward.

So what did the parties talk about instead? Labour’s Robertson said it’s a good news document, showing a crash into recession that isn’t as hard as it otherwise could have been. The unemployment picture is rosy, according to the finance minister. Economists had expected a Covid-19 crash to send unemployment up to 9.8% last month. Instead, it’s around 4%. What’s happened? The government’s wage subsidy programme has poured billions into a leaky bucket over recent months. Once that money runs out, as it will in weeks, the unemployment graph starts jumping up.

Robert MacCulloch, a professor at the University of Auckland, watched Robertson pat himself on the back and wasn’t impressed. “I don’t think anyone can read into that. It’s a meaningless statistic. You’ve paid $15 billion to over a million workers and you’re relying on a technical, statistical label of unemployment,” he said. “I mean, come on”.

Instead of sudden jump in unemployment last month, as the service sector and tourism shed workers quickly, we’ll now see job losses over the next two years. It’s now expected to peak at 7.8% in March 2022. It will then fall more slowly than expected, not coming back to today’s levels before the end of the decade.

“My view is that New Zealand has to look at serious economic reforms and neither National and Labour have any proposals,” MacCulloch told me. “Neither party. Labour wants this to be about the virus and National wants this to be about being better managers of the economy. In the middle of the worst health crisis in a 100 years you think they’d look at fixing the health system and they aren’t,” he said.

“The welfare system wasn’t working so they had to create this wage subsidy scheme, but it was a patch-up job and it meant significant money went to some of our biggest companies. There’s no talk about reforming the system. There’s no talk about really reforming the education system.”

He added: “There needs to be talk about housing. It’s unaffordable today and it isn’t getting better. No party has a real plan to deal with that. I don’t see any move from either side to engage in serious reform at all.”

If a candidate knocks on your door in the coming weeks looking for your vote, you might well ask them: where is your reform package hiding?