The Kim Dotcom challenge to John Key culminated in an extravaganza joining dots from the US, the UK, Russia – even North Korea. And it got very messy. Toby Manhire casts his eye back a decade.

The thing started late, but no wonder – hundreds were stuck outside on Queen Street, unable to squeeze in. When the Moment of Truth began, at about 7.15pm, the crowd roared. Many stood to applaud. Kim Dotcom, in his hallmark black zip-up top, blew kisses and punched the air. “Yes!” he declared. “Yes!”

It was 10 years ago but it feels longer. Monday September 15, 2014. “Tonight we welcome the world to the Auckland Town Hall,” said Laila Harré, MC for the night and leader of the fledgling Internet Party, the Dotcom-funded political vehicle which had recently manoeuvred an expedient merger with the Hone-Harawira-led Mana Movement.

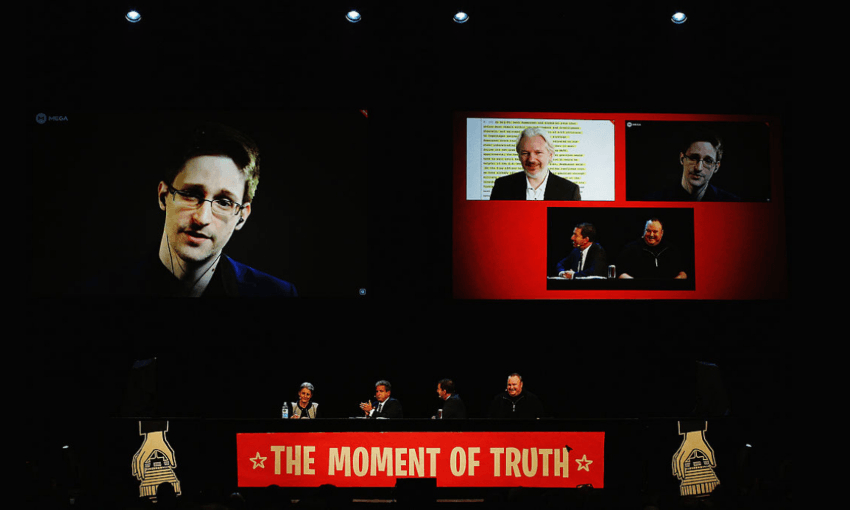

Harré introduced the other guests. Canadian lawyer Bob Amsterdam. American Pulitzer-winning journalist Glenn Greenwald, fresh from being cast by the New Zealand prime minister John Key as “Dotcom’s little henchman”. Gazing down from a screen above, Wikileaks founder Julian Assange. “And perhaps another very special visitor,” said Harré. More cheers from the audience. “Yeah, give it up,” Dotcom hollered. Harré wanted to get on with it. “Settle down,” she said.

As any great spectacle must, the Moment of Truth plaited together several big themes. Kim Dotcom’s zealous response to American efforts to extradite him on charges relating to his file-sharing site Megaupload. The caustic antagonism between the German entrepreneur and the New Zealand prime minister. A furious debate about the surveillance state, fuelled by Edward Snowden’s NSA leaks, revelations that a New Zealand agency had broken the law in spying on Dotcom (and more than 80 other residents, it later transpired) and reforms to New Zealand’s surveillance apparatus.

All that, and an election, at this point just five days away. The Internet Party declared itself “a political movement dedicated to the internet generation”. Critics declared it a political movement dedicated to the preservation of Kim Dotcom.

From the town hall stage, Harré sought to tie the strands together. “Our speakers and panellists tonight are among the mightiest defenders of the internet,” she said. “New Zealanders in this hall are the inheritors of our nation’s democracy and our independence. The battle to defend our internet, our rights and freedoms online and our political and economic independence in the digital age is our battle and we are on the global frontline of that battle right now here in Aotearoa.”

It was an impressive opening, especially given she’d only been seized by the Moment at the last minute. In the lead-up to the event, “Kim had insisted on doing it independently of Internet-Mana,” she told me a few years later. “But in the end it was so clear that there was no way we were going to be able to disassociate ourselves from it that we actively connected to it. I MC’d it, although that was only a decision or request made the day before.”

Harré recalled the event itself as “absolutely spectacular … both in terms of the speakers but also the audience. They heard a story about mass surveillance in New Zealand that had not been heard before.” She’s right about that. Watching back, there were compelling presentations from Greenwald, Assange – whose address was interrupted by a series of drilling and hoovering noises at his then home, the Ecuadorian embassy in London – and Edward Snowden, that “special visitor” she’d teased, appearing via the magic of the internet from Moscow. Key pushed back against many of the claims, but ended up conceding Snowden “may be right” about American cyber-spying on New Zealand.

Among the journalists in the crowd was New Zealand Herald star reporter David Fisher, who had been absorbed in the Kim Dotcom story since it exploded on to front pages with an ostentatious and overblown raid on his Coatesville mansion in 2012. “For Dotcom to find himself on a stage with these people speaking was where he wanted to be,” Fisher told me this week. “He wanted to frame himself as a freedom fighter for the internet. The case that the FBI made against Dotcom painted him in a completely different way, as a fraudster, basically, who was knowingly flogging other people’s stuff to support his own lifestyle.”

Greenwald and Snowden produced documents that revealed New Zealand’s Government Communications Security Bureau had been involved in a project called Speargun, which would have tapped the Southern Cross undersea cable to collect New Zealanders’ communications. Key released his own declassified cabinet papers showing that a decision had been taken not to go ahead with the programme.

Harré again: “I thought it was incredibly important but obviously it wasn’t what the media had been banking on.” There had been a “disappointment in terms of expectations raised”. The expectations were skyscraper-high. Dotcom and the Internet Party had teased a big twist in a different plotline: about John Key’s purported scheming with US movie studios, “and the sordid workings of Hollywood”. But that night, as I observed at the time, the moment of truth as promised never arrived. As a result, the press conference afterwards got very messy.

The best gloss you might put on it is that the promise of a slam-dunk incriminating document was, in keeping with the motion picture theme, a kind of MacGuffin: a device used to attract attention and drive the plot forward, but fundamentally unimportant to the substance, which in this case was state surveillance. And yet, puzzlingly, the damning document that had been planned for that night had already been ventilated, just before lunchtime in the New Zealand Herald. Even more bafflingly it appeared to have been leaked, if not by Dotcom himself, then by someone in his circle.

The email was published in an online report by Fisher. Purported to be a message from Warner Bros CEO Kevin Tsujihara to the Motion Picture Association of America’s Michael Ellis, it was headed “MegaRIP” and dated October 27, 2010. At the time, Immigration NZ was assessing Dotcom’s residency application.

“We had a really good meeting with the Prime Minister,” the message began. “He’s a fan and we’re getting what we came for. Your groundwork in New Zealand is paying off. I see strong support for our anti-piracy effort. John Key told me in private that they are granting Dotcom residency despite pushback from officials about his criminal past. His AG [attorney general] will do everything in his power to assist us with our case. VIP treatment and then a one-way ticket to Virginia.”

It concluded: “This is a game changer. The DOJ is against the Hong Kong option. No confidence in the Chinese. Great job.”

If authentic, this was a giant, billowing, smoking gun. It blew apart Key’s claims he’d never heard of Dotcom until the 2012 raid; it implied he was in the pocket of Hollywood bosses determined to shut down file-sharing sites, that he was complicit in a plot to keep Dotcom in New Zealand (the pesky Chinese were less pliable) so they could swoop and get him extradited into the arms of US prosecutors.

Where had the email come from? As if the saga weren’t already replete with showstopper subplots, Kim Dotcom believed it was linked to a hack attributed to Kim Jong-Un’s North Korea. “That email, I know it comes from hacker circles,” he said in Annie Goldson’s 2017 documentary Kim Dotcom: Caught in the Web. “You know about the famous Sony Hack? The same people who were responsible for that hack were responsible for this hack.”

One way or another, that email landed in Fisher’s inbox. “It all happened very quickly,” he recalled this week. “There had been huge anticipation building given Dotcom had said for at least two-and-a-half years there was a grand conspiracy against him. The email arrived at something like 11am and was debunked by 1pm.”

Fisher continued: “The curious thing was that the email was the perfect missing piece in a puzzle – the perfect person to the perfect person at a perfect time, and it ticked all the boxes in terms of content.” He immediately called Dotcom. “I said, ‘is this what you are planning to produce tonight?’ He said, yes, it was. We had a quick chat among a few editors as to how to proceed. Given how pressing time was, given we were just a few hours out from the doors opening at the town hall, and the idea of wrestling comment out of Key’s office and Warner Bros overseas was really unlikely, we decided to publish. We decided to tell the story in somewhat of an iterative way.”

Up the story went on the Herald site, couched as authenticity-unknown but confirmed as Dotcom’s intended revelation. “We went to Key’s office and then Warner Bros, saying we’re running this right now – is this email true? We got very quick responses. We were very quickly able to have reporting up with them saying, ‘no, it’s a fake.’ The Moment of Truth came around, and the emperor had no clothes. The email and the way it unfolded made it a very hard thing for anyone to believe.”

As to the origin of the email, “I can’t say where it came from but I can say it’s a source I wouldn’t be inclined to dismiss out of hand,” said Fisher. Was there any perception that Dotcom was disappointed at being gazumped by his own revelation? “I don’t have a recollection about that,” he said. “I would say that me asking the question and him confirming it suggested he wasn’t averse to it coming out. All he needed to say [to pause publication] was, ‘wait a few hours and you’ll get your answer at the town hall tonight.’”

In 2017, the Serious Fraud Office confirmed it had completed an investigation into the email. “As a result of that investigation, the SFO is satisfied that the email was a forgery,” said a spokesperson in a statement to Fisher.

At the time, Dotcom said he continued to “believe the email to be real”. When I asked him the question again this week, he didn’t answer directly, instead saying, “The email that was provided to us had no connectivity data and it was the advice of my lawyers not to use it.” Dotcom made the same point in Caught in the Web. “I was assured that email would contain headers, which … would allow anyone to verify the contents. But unfortunately that email was not leaked with that information, so it became useless to me.”

In his email this week, Dotcom added: “Any reasonable person in New Zealand knows that John Key knew about my case well in advance and lied to the public about it. Only fools believe that John Key didn’t know about an operation that was a high priority for the White House because Obama and Biden needed to secure Hollywood funding for their re-election campaign.”

Key has consistently rejected such claims as baseless conspiracy theories.

As to the night at the town hall, Dotcom said, via email: “It was a significant event because it showed that the New Zealand government was making preparations to commit unlawful mass surveillance against all New Zealanders. The magnitude of the revelation by Edward Snowden was downplayed by the media because I didn’t make the event about my case.”

That mysterious, premature, much-hyped email – coupled with the emphatic denials from Key, the Motion Picture Association of America and Warner Bros – ultimately hamstrung the big Moment. “The decision about how to deal with it was changing every hour in the couple of days before the event,” Harré said in 2017. “When we went on stage, I believed that there was going to be a revelation, and that there was going to be a full explanation given of all this, which I believe would certainly have been convincing enough for those who could be convinced … But that didn’t happen, so I’m still not quite sure when decisions were made and why, but, you know, Kim has taken a lot of risks on the legal side of his case, and I absolutely know that it was his lawyers and not him who were urging caution.”

John Mitchell, then leading the press operation for the Internet Party, recalls pacing around the perimeter of the town hall that afternoon, reading the email – its publication had blindsided him. “I couldn’t fathom what was happening. It was incredibly strange. It made that whole Moment of Truth a different beast, to be honest,” he said, a decade on. “The fact that it happened on the day of the event, this email, and then all the questions about it, really threw a major spanner into the works.” On the face of it this was explosive. “This was the smoking gun we’d been looking for – there’s direct collusion between a multinational media company and the New Zealand government.” But as he kept reading the email, something nagged at him. “To me it seemed way too convenient … it was too perfect,” he said.

“There was a lot of discussion, and it was pretty clear to me that Kim Dotcom and others in his higher-up group of people had concerns. It was basically left right up until sort of the last minute to say: we’re not going to use that.” That decision – the email was mentioned once, fleetingly, by the lawyer Bob Amsterdam, who said “the Internet Party has referred the matter to the Parliamentary Privileges Committee” – lit the fuse on an incendiary press conference in a room off the main auditorium following the event. Mitchell and Simon Wilson had a stand-up row. Patrick Gower asked repeated questions about the provenance of the email, with the persistence of a pneumatic drill. Harré, Mitchell and co said that wasn’t up for discussion, as it had been sent to parliament. “Do your job, Patrick!” Dotcom blasted, over and over again, jabbing his finger in the direction of the 3 News political editor. The media, Dotcom said, “have failed us … You need to wake up and do your jobs”. Greenwald, as best I can remember, sat mostly silent and bemused.

“It did get rather heated,” Mitchell said. “And obviously a lot of it centred around that email, a lot of it centred around: what’s the point of all of this? It was one of the more interesting press conferences I’ve run in my life.”

For Gower, the day was a blur, “in more ways than one”. He told The Spinoff this week: “My retina had detached a few days before, and I’d been off the campaign trail. I’d had an operation to reattach my retina, and managed to somehow drag myself back for the Moment of Truth. So I could hardly see a thing … I couldn’t put my contacts in so I wore my glasses, which I hardly ever did in public, and I was distinctly uncomfortable. I couldn’t actually see. But the actual night itself is a total blur as well.”

How so? “It was the culmination of an incredibly weird election campaign that had come on top of an incredibly weird election cycle with this incredibly weird Kim Dotcom show that had shifted from him being some sort of Robin Hood kind of character to potentially something a little different. And this ongoing battle between him and Key was massive. If you were to tell someone today: ‘Yeah, so a computer expert is going to hole up at the mansion of New Zealand’s richest people. He’s going to be chased by the American government, and he’s going to get locked in a mano-a-mano battle with the prime minister, and it’s going to consume most of the political energy of the country for the next two or three years culminating in a massive Auckland Town Hall “Moment of Truth”,’ people would just go, whaaaaat. So if you look back on what actually happened, it doesn’t actually make any sense. There we were, crammed into the town hall, waiting for something. Then it just didn’t really come.”

The last box-office scene in the Key-Dotcom saga had played out just over a year before, at a parliamentary hearing on the planned changes to surveillance legislation. “Oh, he knew about me before the raid. I know about that. You know I know,” said Dotcom, eyeballing Key across the select committee room. In keeping with the reliable bathos of the wider story, the exchange continued as follows.

Key: “I know you don’t know. I know you don’t know.”

Dotcom: “Why are you turning red, prime minister?”

Key: “I’m not. Why are you sweating?”

Dotcom: “It’s hot. I have a scarf.”

The animus between the two men and the debate around state surveillance became a lightning rod for opposition to Key and his government, which ranged from the principled to the unhinged. At an Internet Party rally, Dotcom led a “Fuck John Key” chant. The same message was scrawled on handmade signs outside the town hall on September 15. Pictures of the prime minister were adorned with devil horns.

“People thought that John Key was going to be brought down once and for all, and that actually fed into a much bigger narrative that went back before Dotcom was even on the scene,” said Gower. “There was always a feeling among some on the left that John Key had something to hide, that John Key was a Trojan horse, that John Key had some big dark secret. So [that night] fed much deeper, in my view, into the whole aura of John Key.” Some of those perched on the edges of their seats “expected this killer blow … The mask will slip – finally there’s something on this guy. Slippery John will go no further!”

The public part of the town hall event ended with an exhortation from Harré. “The Moment of Truth has delivered,” she said. “It is up to every person in this hall to speak the truth, to share the truth, and to vote for the truth on Saturday.” A chant went up from the crowd: “John Key out!”

The 2014 campaign had already been buffeted by scandal, emerging from the Nicky Hager book Dirty Politics. Eighteen years earlier the investigative journalist had exposed New Zealand’s part in a formidable international surveillance machine in the book Secret Power. This time Hager had drawn on a trove of leaked correspondence to reveal the links between the ninth floor of the Beehive and an attack blog. National had attempted to cast that episode as a sideshow, a distraction, and when the Moment of Truth came along, they did the same.

Watching the event on a livestream from a hotel in Hawke’s Bay, campaign chair Stephen Joyce quickly judged that it would “move the dial”, he told the Spinoff last year, “in our favour”. While the Dirty Politics scandal had delivered a “wearing effect on our poll numbers as the weeks went by”, voters had at the same time become “frustrated that so much airtime was being given to ‘the game’ of politics rather than issues important to them”, he wrote in Stephen Levine’s post-election collection (which played on the Dotcom extravaganza for its title: Moments of Truth). Joyce believed that what voters would see that night was “a group of people, mostly from overseas, brought in and beamed in to tell New Zealanders how they should vote in just five days’ time. They were there to reveal to New Zealanders they had apparently been duped by the governing party, and they needed to remove the scales from their eyes if they knew what was good for them. It had overtones of the dumb locals being lectured by international types who knew best.”

He added: “The Moment of Truth was the straw that broke the camel’s back for dirty politics. All the weeks of frustration about what had been a soap opera of a campaign boiled over and a whole lot of New Zealanders suddenly decided they had had enough and they wanted their election campaign back … Overnight the mood for National became a lot stronger. And over the next few days, we picked up the mood change, as the prime minister said at the time, very strongly. Our voters were energised and determined to vote. I have never seen in four elections such a strong attitude.” Key’s National would go on to win a third term – and win with sufficient numbers they didn’t need to turn to Winston Peters.

If the night marked a turning point in the election, it also felt as though the air started to leak from the Dotcom bubble. The energy for the exploits of the flamboyant German – his feuds, fast cars and legal battles – discernibly began to dwindle.

The Internet Party was in itself a laudable enterprise, Mitchell argued. Even if it got lost in “the shadow Kim Dotcom cast” and struggled to find “ideological alignment” in the “frankly crazy” marriage of convenience with Mana, it did make a timely case for a technology-led economy and “develop really robust, well-researched policy positions on a number of things … I was pretty proud of what we were able to achieve. It’s just a real shame that the wheels fell off at the end.”

Dotcom’s battle with the US Department of Justice, now in its 13th year, continues. In August, the justice minister, Paul Goldsmith, signed Dotcom’s extradition order. “The obedient US colony in the South Pacific just decided to extradite me for what users uploaded to Megaupload, unsolicited, and what copyright holders were able to remove with direct delete access instantly and without question. But who cares? That’s justice these days,” said Dotcom in a post to X/Twitter. He is expected to seek a judicial review.

Fisher, who continues to write about the Dotcom story for the Herald, still brings up the Moment of Truth when he speaks to postgraduate national security students, many of whom are likely to be recruited by surveillance agencies in the years to come. He shows them a photograph of the night taken from behind the participants on the stage, looking out at an overflowing town hall. The people there that night were “engaged in issues around surveillance, privacy and liberty. They turned up because they were concerned,” Fisher tells them.

“That’s why transparency is so critical. If you screw up you have to be open. If you don’t, there will be characters that will take advantage of that.” He points to the photo and he says to the students: “That’s what a loss of faith looks like.”