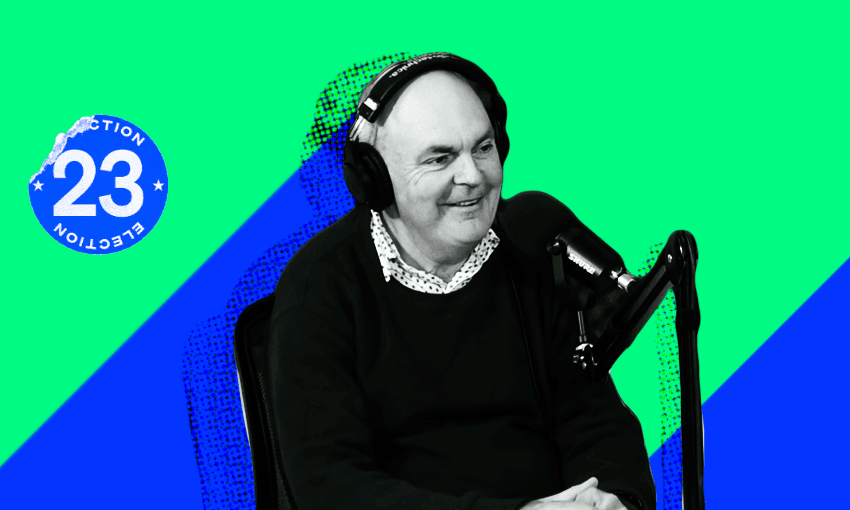

From Mr Fix-it to Phone-a-friend, the former senior minister and brains behind five National Party campaigns shares his secrets.

Everything might have been different had it not been for Scott Morrison.

Following a disastrous 2002 election that saw National plummet to less than 21% of the vote, Steven Joyce was appointed to the new role of party general manager. He travelled to Australia to observe the Liberals’ federal election campaign. “I took a lot of notes, copied the campaign structure diagrams, and noted the professionalism of the organisation and the structured approach they took to each day,” writes Joyce in his new memoir, On the Record.

In the absence of any sufficiently qualified New Zealand contenders, Joyce met an Australian candidate for the role of National campaign director for the 2005 campaign, a “guy called Scott Morrison”, the Liberals’ New South Wales state director who had spent some time working for the tourism minister in New Zealand. A surprise victory for John Howard in Australia led to Morrison being approached for a soon-to-be-vacated federal seat, beginning a parliamentary career that would eventually take him to the prime ministership.

“He would have been great,” said Joyce in an interview on the Spinoff politics podcast Gone By Lunchtime. “But he got the call to stay in Australia … and about a year out, he said, I can’t do it. So we were sort of stuck, and Judy [Kirk, party president] was looking around, and said, how about you? And I’m like, oh well I’m not doing anything. This could be a fascinating challenge. Let’s do it.”

Follow Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts.

That was the first of five campaigns that Joyce would run for National, with leaders Don Brash and Bill English bookending three John Key led victories. The first of those, in 2005, saw Brash surge into the front off the back of his infamous Orewa speech, before dwindling amid controversy around links to the Exclusive Brethren.

Today, Joyce defends the divisive John Ansell-designed “Kiwi / Iwi” billboards. “People read more into that than was ever intended. They saw it as a derogatory thing, but actually it was intended as a sort of clever wordplay.”

Of the 2011 campaign, in which Phil Goff came a cropper in a clash with John Key when trying to defend, among other things, a pledge to remove GST from fruit and vegetables, Joyce said that was an example of the potential for debates to “provide catalytic points”. He said: “[Before] the Show Me the Money thing happened, we’d been banging away for some time about our concerns about what Phil Goff was promising, and feeling that it was very detached from the reality of where the country was, with the earthquakes and GFC and so on. On the surface, we weren’t getting a massive amount of traction with that. But it was building. And then John made that line in the Christchurch Press debate …and, job done. I mean, John didn’t know that was going to have the impact it did, I don’t think, ahead of time. But it worked. And he had the smarts to stop there. It was done. Debates allow for those moments.”

Good campaigns needed good plans, but it was equally critical to be sufficiently nimble to deal with the unexpected, said Joyce. “You’ve got to have a really good campaign system. Because there’s huge potential for the wheels to fall off in an election campaign. And one thing I learned from the Liberals when I went over there was they have a machine. Everybody knows their role. There’s a rhythm to the day and they rely on that rhythm … And that provides you with a scaffold for when things go wrong. And they always go wrong.”

They could go wrong in small ways, such as the time Tauranga MP Bob Clarkson dominated a day’s headlines after being televised discussing his need to “drain the spuds”, and bigger ones, such as Don Brash blurting on student radio about his conversations with the Open Brethren. “You just have to go: right, OK, here’s where we are, where do we go now?” he said. “You just need to be able to reassure your team that this isn’t the end, there’ll be another thing along tomorrow. And politics, as my friend Wayne Eagleson [Key’s former chief of staff] says, is not a game of perfect.”

The better known scatological moment in the Joyce archive involved a sex toy – or, to be definitionally accurate, a squeaky pecker – that was thrown by a protester at Waitangi. It bounced off his pate and went viral, culminating in an all-singing, all-dancing, all-dildo tribute from John Oliver on US television.

“I could have just said, ‘right, well, that’s not good enough’,” he said of his response. “And when the police came and asked me about pressing charges, even though it’s their decision … I just thought that it was best just laughed off. Because it was sort of funny. And there is a part of me that is anarchic radio from way back … In student radio, we used to go around gifting cabbages to the general manager of 2XS and stuff. I think it was [best] not to take it too seriously. Because the world doesn’t need more of that sort of offense to be taken. And nobody got hurt. We dusted ourselves off and went on our way.”

Today, it remains “constantly used on social media as a form of insult to me, which I find amusing, because I don’t think it was something I caused. … But if somebody wants to have a go at me on social media, they generally pick up a meme of that and throw at me.”

Having helmed campaigns that, even from opposition, channeled some optimism, in the “brighter future” coinage, what does he make of the National slogan “Get New Zealand Back on Track”? “Every election is different, and every situation is different,” he said. “And I’m assuming that worked out that a lot of people think the country has gone off track … There is a sense the country has gone off track somehow in the last five or six years, that’s shared by many people. And it was a successful campaign for Wayne Brown – in his own way, it’s a bit different to what the National Party is doing. But politicians respond to public concern, as a general rule.”

In 2017, the National plan was thrown off course by Labour’s 11th-hour leadership change. As Jacindamania dominated everything, Joyce realised he needed a big intervention. “As campaign chair I knew I had to do something to change the game, but what exactly?” The answer was the “fiscal hole”, in which Joyce held a press conference and declared – to a mixed response – that $11.7 billion was missing from Labour’s costings.

Reflecting on that, and the recent re-emergence of fiscal hole rhetoric, would he now accept the case for an independent fiscal assessment unit? Not quite. “I think the risk is that it just adds another player. I would go and look at countries which have those things and ask, does that remove those debates in the UK and in the US? I’m not saying we won’t end up with one. But I just think people are probably a bit naive if they think that that’s going to solve the argument.”

As for the National Party’s self-immolation in the couple of years before the 2020 election, Joyce puts it down to inflated expectations and underestimating how exceptional John Key had been. “I don’t think it was inevitable at all,” he said. “The trouble is that sometimes in organisations, people think that anybody can be the leader. And … they’re also not as common as some people think. It’s actually a really tough job. And, obviously, too many people thought that they could do it … It looks easy. Suddenly, everybody thinks they can do it.”

These days Joyce plies the lucrative trade of consultancy, and stays for the most part out of National Party matters. He does, though, take the occasional call. “If anything I’d describe myself as a phone-a-friend.”