It’s called ‘CANZUK’, and it’s a bad idea. New Zealand should not be suckered in by dreams of Empire 2.0, writes Lewis Holden.

The clock struck 11 on January 31, 2020 and it was all over. Britain was out of the European Union after 47 years. Under the much-maligned Brexit deal there’s still another 11 months of the transition period to go before the EU’s long regulatory tail is cut off. That means the UK will engage in a whole lot of negotiating, mainly with the union Britain has just quit, but also with an administration in the US that is better known for its protectionist leanings than supporting free trade. And while that’s going on, an alternative to both the EU and US is being touted – with the awkward acronym of CANZUK – a free trade and free movement bloc of former British colonies. New Zealand should not be suckered in by dreams of Empire 2.0; Britain’s complete exit from the EU offers us an opportunity to free trade with Britain, but not one to override all others.

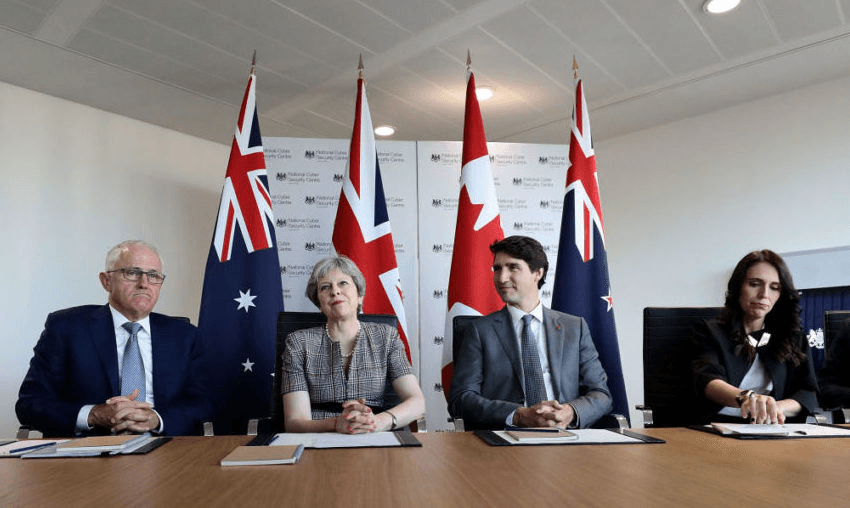

CANZUK – Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom – is the idea of free trade and free movement between Britain and three of its former colonies. Not coincidentally, the three former British colonies are nation states with settler majorities, a fact that leads to some fairly squeamish responses from its proponents when this fact is pointed out. Those proponents claim that the three former settler colonies are included because they are all Commonwealth members. Other dynamic economies in the Commonwealth such as Nigeria, India and Singapore are excluded, for the mortal sin of not having the Queen as their nominal head of state.

And then there are Commonwealth members that do still have the Queen as their head of state, such as Jamaica and Papua New Guinea. They are excluded because they are not “developed” enough. This is despite centuries of scholarship showing free market access is the best way to help poorer countries develop and increase mutual prosperity. It’s not hard to figure the real reason Jamaica, Papua New Guinea and others are excluded.

CANZUK is touted by a number of politicians in Britain and appears to have strong support among Canadians politicians. In Australia and New Zealand political support has been harder to nail down, with National leader Simon Bridges of National and David Seymour of ACT cautiously lending moral support for the idea, especially in terms of free trade. Australia is cooler towards the proposal, with a backbench senator being CANZUK’s only apparent friend at a federal level. While polling appears to indicate strong support in principle amongst the general public, supporters of CANZUK itself are all over the place when it comes to trade and free movement.

Some suggest CANZUK is an economic union, others that it means a return to preferential trade, something that ceased to exist across the British Empire in the 1930s. Some even go so far as to argue for the exclusion of the much-hated European Union and sometimes even the United States. For Britain that would be economic suicide: the very reason why British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has put so much emphasis on getting a free trade deal with the European Union as that the trade bloc accounts for 45% of the UK’s exports. As a country, the United States is Britain’s single largest trading partner, taking 18% of the UK’s exports. The EU and US cannot be excluded and in reality, are the trade policy priority for Johnson’s government.

For Australia and New Zealand that means working towards bilateral free trade agreements as quickly as possible. That could be harder for us to achieve than it appears, especially given previous statements about the potential for high tariffs on agricultural exports to the UK in the event no deal is reached with the European Union. Our own trade negotiating teams are, rightly, focused on a bilateral agreement with the European Union. Britain is an additional opportunity. Again, the political reality for Britain is that trade deals with Canada, Australia and New Zealand are much more important in a political sense than they are in an economic sense. And since New Zealand already has free trade agreements with Australia and Canada, a trade deal with Britain gives us the CANZUK trifecta anyway, without the unnecessary pain of four-way negotiations.

That only leaves the question of free movement on the table. Technically, this should be the easy part. Politically, it is even more fraught than the question of free trade. While New Zealand, and other Commonwealth members, will most likely benefit from changes at the margins (possibly a restoration of the old ancestry visa rights and an expansion of overseas experience visas), the political chances of free movement are slim. British High Commissioner to New Zealand, Laura Clarke, essentially confirmed this in a recent interview with Radio New Zealand’s The Detail. The High Commissioner made clear that Britain did not want a return to the 1970s. So no miner’s strikes or free movement for former British subjects it seems.

Ending unfettered immigration to the United Kingdom, or at least the perception of it, was a primary driver for those who voted for Brexit. As much as the bureaucratic overhead of the European Union may have rankled, its lack of democratic processes and a general sense of despondency over Britain’s decline in the world, it was – to paraphrase the Daily Mail – stopping immigration what won it. It is impossible to imagine Britain acquiescing to a request for free movement, even from countries with populations that are a majority of English-speaking descendants of Britons. In any case, Australia has taken free movement off the table early in its negotiations with the United Kingdom.

Which in the end leaves very little for New Zealand out of any CANZUK proposal. Support for the idea might exist, largely due to nostalgia for the British Empire, but its benefits are small. We are likely to get a good free trade deal with Britain anyway, because politically it looks good for Boris Johnson’s government. More importantly, the daydreams of Empire 2.0 or a return to Empire preferential trade will only lock New Zealand into an ill-defined union that makes no sense given the massive opportunities across our region. Free trade is a force for good and ought to be promoted globally, not in an attempt to reanimate a long-dead empire.

Lewis Holden is a former National candidate and campaign chair of New Zealand Republic