The scrap between the National Party opposition and the Labour MP speaker is an example of the Nash Equilibrium, and it leaves Danyl Mclauclan reflecting on a deeper sorrow and madness

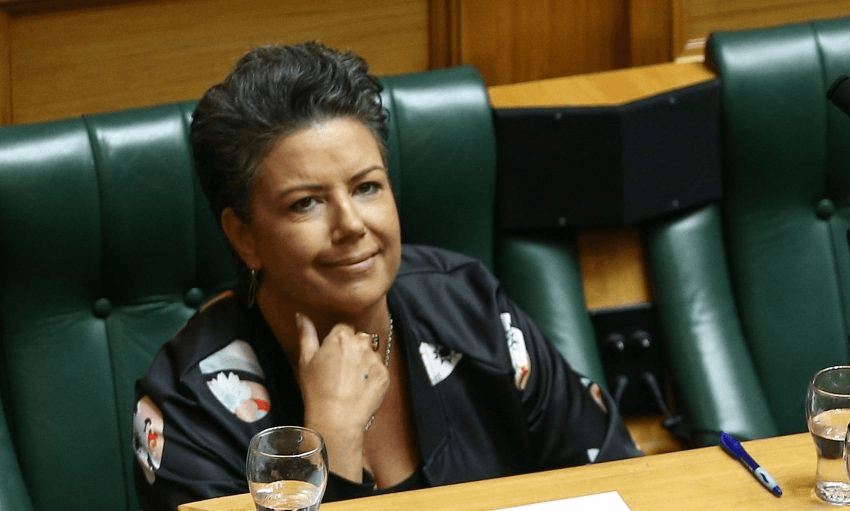

National deputy leader Paula Bennett is unhappy with the Speaker’s rulings during Question Time. This is not an important issue and you don’t actually need to know or care about it; but it can be a helpful way to talk about deeper problems in our politics that you probably do care about. So here we go.

When you’re watching the news and you see clips of our politicians screaming nonsense at each other and storming out of parliament you’re almost always seeing Question Time. It runs for about two hours every Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday when the House is in session (which is about 30 weeks a year). It’s not very representative of what goes on in parliament which tends to be process driven, legalistic and incredibly boring, or of what politicians do all day which is have meetings with each other and their staff and various officials and interest groups, and chase media stories. But because of its absurdity Question Time gets the most TV coverage, so it tends to dominate public perceptions of politics, which is one of the main reasons those perceptions are extremely negative.

Why even have Question Time? The theory is that Question Time is when the opposition holds the government to account. They can ask ministers any question related to their portfolio and the minister has to answer truthfully. Who decides if the government’s minister has answered truthfully? The speaker of the House. And who appoints the speaker? The government. So this works about as well as you’d expect it to.

Questions are asked in two formats. There’s the primary question which is given in writing by 10am of the day the question will be asked in the House. The minister’s staff then rush around researching the topic and writing a reply which the minister repeats or just reads out loud. The opposition can then ask supplementary questions and the minister doesn’t know what these will be so there’s always a slight chance of a “gaffe”, ie the minister accidentally telling the truth about the government’s performance or policies. But you only get a set number of supplementary questions so you need to use them carefully.

The current speaker of the House is Trevor Mallard, and one of his tools for enforcing order during Question Time is to deduct supplementary questions off the opposition whenever they do or say something he doesn’t like, which is frequently, and is based on an unknown standard of behaviour that seems rather arbitrary. This is why Paula Bennett argues that the speaker’s rulings are “dangerous for democracy”. He’s taking away one of the only tools the opposition has!

See also:

A critical analsysis of parliamentary power-sits

How to fix Parliamentary Question Time: Gerry Brownlee, James Shaw, Collins & more write

On the one hand, Bennett has a point. On the other, it’s very hard to have any sympathy for National given the behaviour of the previous speaker, National’s David Carter. Carter didn’t deduct supplementary questions. Rather, when Labour asked John Key a question, no matter what it was about – the economy, welfare, defence, whatever – the prime minister would almost invariably ignore it and shout at the opposition, telling them they were a pack of losers and idiots. The opposition would complain that the prime minister hadn’t answered the question and the speaker would reply that he had indeed answered, he just hadn’t answered to the opposition’s satisfaction, but that wasn’t his problem. And this would repeat itself down the supplementaries.

The speaker before Carter was National MP Lockwood Smith who was generally regarded as being a fair and impartial speaker, especially compared to his predecessor, Labour’s Margaret Wilson who had a similar approach to Carter: Ministers must “address questions”, she ruled, but that was not the same as answering them. National were enraged by Wilson, just as Labour were enraged by Carter and National are now again enraged by Mallard. It’s not hard to see the pattern there. And it is bad for democracy.

So why doesn’t parliament fix question time, especially when it makes them all look terrible? There are plenty of suggestions for making it better. What if you had prime minister’s question time where the PM was held account for the performance of their government? And/or what if the speaker needed to be re-elected every year with a two-thirds majority to incentivise them to rule impartially? Or you could have the speaker come from the Opposition? At the very least you could get rid of the patsy questions, where government backbenchers hold their own ministers to account by demanding they tell the house what a brilliant job they’re doing. And yet none of these things happen. Why?

Look at it from the government’s point of view. Sure, they could hold their own prime minister up to higher scrutiny, and have a speaker that compelled ministers to answer, they could get rid of patsy questions; and sure, that would all be good for democracy and good for them in the long run, when they’re back in opposition. But it would be bad for them in the short run and there’s no guarantee whatsoever that National would abide by those changes. So they might pay a high upfront cost for no gain whatsoever. Which means that the smart, rational thing to do is stick with the status quo, terrible though it is.

Economists have a term for this exact situation: they call it a Nash Equilibrium and it can be summed up as “a situation in which everyone is doing the best they can given what everyone else is doing”. If you’re a strategic actor in a competitive environment – like politics – everyone is incentivised to adopt the best strategy for themselves, given their best guess about what their competitors will do, and that often works out as a very poor long-term outcome for everyone. But it can be very hard to break out of.

Here’s another example: back when National was in power Labour and the Greens were outraged at the government’s abuse of the Official Information Act. Now they’re in power and journalists are complaining that the new government’s abuse of the act is even worse than the old one. Which makes sense, because the new government has no incentive whatsoever to be more transparent than the old one was. They could be more transparent but it would be bad for them, and the next government could just go back to non-transparency. Why doesn’t the government reform the rules around lobbying and political donations? Exact same deal.

Once you start looking for bad Nash Equilibriums you see them everywhere. Traffic congestion is a classic. It’s faster for everyone to drive somewhere in a car so everyone does that, so everyone gets stuck in traffic, so the government builds more roads, which increases the incentive to drive, so more people do so, so the traffic congestion gets even worse. Why do I still have a Facebook account when I know that Facebook is such a malevolent force for evil in the world? Because everyone I know is on Facebook and that’s how we all stay in touch. There’s no easy way for us all coordinate switching to some new social platform so we all keep using Facebook even though we know its a bad thing. Why is it so hard for the countries of the world to coordinate greenhouses gas reductions? A number of reasons, but continuing to emit carbon because everyone else is still emitting carbon and its not in your short-term interest to pay the economic cost of emissions reduction is a major one. Arms proliferation? Another classic Nash Equilibrium.

When we look at what’s wrong with the world our brains tend to identify and blame members of rival groups: enemy political parties, or races or ideologies or economic classes. Surely, we reason, if we get rid of that bad group and replace it with a good group our problems will be solved! And sometimes they are but mostly they aren’t, and we’re often puzzled by that, or conclude that the new group aren’t actually good so maybe they need to go, too. But if you put good people into situations with bad incentives they’ll either respond by playing the game according to those incentives or losing out to those who do. And changing incentives in a political system is often hard, because the people with the power to deliver that change are those who are empowered by the status quo.

At this point people sometimes talk about major systemic change. The whole system is broken! We need a new one! But designing political systems in which politicians’ incentives align perfectly with the interests of the public is very hard. Most international comparisons rank New Zealand as one of the most transparent, least corrupt, most open and representative democracies in the world.

It’s one of the main reasons political change is harder than it seems; why good people do bad things; why obviously broken systems aren’t fixed; and it’s the reason Paula Bennett’s self-righteous frustration with Trevor Mallard is both the source of short-term amusement and a symbol of the deeper sorrow and madness that lies like a splinter in the heart of our politics and our world.

The Bulletin is The Spinoff’s acclaimed, free daily curated digest of all the most important stories from around New Zealand delivered directly to your inbox each morning.