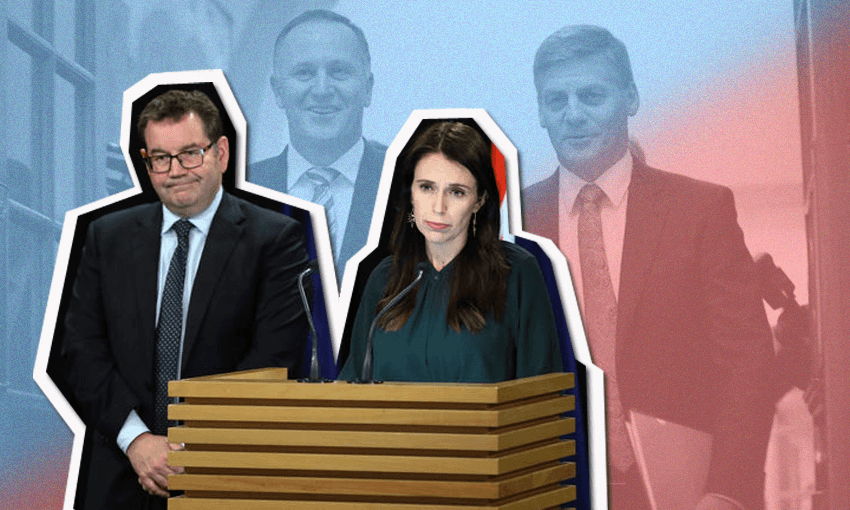

Labour has made an extraordinary ascent in the polls and is now clinging to a mostly non-threatening brand of centrism. Hayden Donnell counts the cost of that strategy.

Cast your mind back to 2016. As Bill English rolled out his budget, Grant Robertson issued what looked like a criticism. In an article headlined “a Budget that lacks vision and courage to make life better”, he accused English and prime minister John Key of “refusing to take on the housing crisis”.

He wrote: “It is astonishing that nothing has been introduced to tackle demand in the housing market and that there’s nothing for first home buyers locked out of the Kiwi dream of homeownership.”

Many people would have taken Robertson’s words as a promise to be more visionary and courageous once he became finance minister. They made a big mistake. Last week, Robertson issued a release clarifying his position: Key and English were actually good at running budgets, he said, before excoriating his National Party rival Paul Goldsmith for clumsily misplacing $4 billion in his financial plan. “There is no John Key or Bill English there any more. No one who knows how to run a budget would have made a basic mistake like this.”

Robertson’s implied pitch to Key and English’s voters is that Labour is the real heir to the fifth National government. It’s him – not Goldsmith – who’s really carrying on the proud traditions of the pair who, in his own words, lacked the “vision and courage to make life better”.

There’s at least a grain of truth to the sales pitch. Over the last few months, Labour has presided over New Zealand’s biggest upward redistribution of wealth since Key and English paid for tax cuts that primarily benefited the rich by adding the cost onto poor people’s grocery bills. While keeping people in work, the $14 billion Covid-19 wage subsidy has delivered huge, government-subsidised profits to the shareholders of some of New Zealand’s richest companies.

At the same time, the Reserve Bank has kept interest rates at record lows, gifting property owners a $64 billion support package and flooding our already thermonuclear housing market with cheap cash. House prices have implausibly gone up. Rents have too. New Zealand’s landed gentry is richer than ever before while people who don’t own a home are often worse off than they were under Key. If first homes were out of reach in 2016, they’re now a disappearing speck on the horizon, hurtling toward outer orbit.

Politicians can defend these distorted conditions: the wage subsidy was necessary to keep the economy afloat during a global pandemic, and low-interest rates stimulate spending which keeps people in jobs. These arguments would be more palatable if the government was also taking brave steps to mitigate the widening inequality its own policy settings are creating.

Instead, it has clutched tight to its political capital. At the midpoint of Tuesday’s leaders debate between Labour leader Jacinda Ardern and National leader Judith Collins, Auckland City Missioner Chris Farrelly asked a question about the people he sees who are poor and getting poorer. He talked about parents working two or three jobs and still struggling to pay rent and put food on the table. “If you’re the next government what is your plan for addressing income inadequacy and wealth inequality in New Zealand?” he asked.

In response, Ardern talked first about state house construction. The government has built or is in the process of building roughly 7,000 houses and is planning 8,000 more. It has lifted the minimum wage, put benefits up $25, and advocated for more employers to pay a living wage. If she had more time, Ardern might’ve added that it had taken steps to enable affordable housing, most notably by eliminating mandatory parking minimums and stopping Nimby-possessed councils implementing density controls in the places most people want to live.

Those are real achievements, but the answer was notable for what wasn’t mentioned. The government has also fallen far short of the recommendations from its own welfare advisory group which has called for core benefits to be immediately raised by up to 47%. Economist Shamubeel Eaqub says implementing those recommendations would immediately smooth the sharpest edges of inequality while helping stimulate the economy because people on low incomes spend most of their money. Keeping those people in poverty is a political choice, he says. “You don’t win elections by promising to pay more on benefits. Even in a pandemic, even in a big recession, even if it will actually make New Zealand better and help the economy.”

Instead of meaningfully adjusting benefits, Labour has taken what, in some cases, seems like an actively punitive approach to those struggling with rising rents in a spiralling housing market. On Monday, Newsroom’s Dileepa Fonseka reported that the party was reviving its plan to charge people 25% of their income to stay in emergency housing. Social welfare minister Carmel Sepuloni said the charges were to “incentivise” people to move into transitional homes or private housing, though Eaqub is doubtful that many families are truly choosing to cram long-term into cheap motel rooms because they love the feng shui. “It’s stupid. It’s disgusting,” he says. “You failed in the first instance by not building enough social housing, and now you say because you’re on the bones of your arse, we’re going to take more money from you, and if you can’t pay it then we’re going to put you in debt.”

Labour’s tax policy also seems designed to lock in existing inequalities. Its sole adjustment would be to raise the tax rate to 39% for incomes over $180,000 – the top 2% of earners. There’s no tax break for the working poor; no demand that property owners share any of their government and Reserve Bank-enabled profit.

The Greens have proposed a more progressive tax system, calling for a guaranteed minimum income funded by a tax on wealth. But Labour wouldn’t have to copy its actually leftwing allies. Eaqub points out that the tax system under Scott Morrison’s Australian government has a 0% tax rate for people’s first $18,200 of income, and a 45% rate for incomes above $180,000. Boris Johnson’s UK government also has a tax-free threshold of £12,500. “I just look at Australia in particular and I think ‘how is it that they have a tax system that is so much more progressive than ours?’,” Eaqub says. “New Zealand has this myth about how we’re a highly taxed country, and we really believe it. When it comes to wealth or higher incomes, we’re not highly taxed, and there’s a lot of vested interests in keeping it that way.”

Labour under Robertson is too pragmatic and sensible to follow in the footsteps of known pinkos like Scott Morrison and Boris Johnson. It has instead pursued policies that have left it unable to truly address the magnitude of the problems facing the working poor, beneficiaries, and just about everyone who doesn’t already own a home. Last month, health minister Chris Hipkins said free dental care was off the table because it’s unaffordable in the “current economic environment”. Maybe that’s true, but it’s hard to square with the government’s lack of similar qualms about propping up Briscoes’ profit margin.

The truth is Labour doesn’t want to fight for a tax system that could fund free dental care, or for a budget that prioritises that kind of expenditure above dumping gold into a Scrooge McDuck-style vault inside Rod Duke’s Herne Bay mansion*. Former Labour advisor Clint Smith describes its strategy as a play for broad-spectrum political dominance. In his eyes, the party wants to create a kind of eternal government of the median New Zealander, and to slowly, but enduringly, tilt politics in a slightly kinder direction. To do that, it needs to avoid annoying even a single rental property-owning Boomer, who it fears will switch their vote back to National the second someone looks at their $4 million capital gain the wrong way.

That’s an easy calculation to justify in the abstract. It’s much harder in the real world. The bill for Labour’s hoarded political capital is paid in a grim currency: young people locked out of the housing market for good, renters paying 65% of their income to rapacious landlords, and desperate families handing over 25% of their pay cheque to authorities who want to be sure they’re not getting too comfortable in their motels. All this is taking place while the already rich reap the benefits of a generous tax system and eye-watering profits on property under the watchful eye of a supposedly left-wing government. If that’s the cost of popularity, Labour’s leaders have signalled they’re willing to stump up. But they’re not the ones actually paying the price.

* The existence of this vault has not been independently verified